Due to their length, short films are always screened as part of a programme comprising several films. Compiling a good programme is a creative challenge that requires a professional approach. Far too little attention is paid to this task, which involves mediating between filmmakers and the audience. And yet the way in which short films are compiled to form a programme and how they are then presented plays a vital role in their acceptance, their reception and ultimately their success.

Due to their length, short films are always screened as part of a programme comprising several films. Compiling a good programme is a creative challenge that requires a professional approach. Far too little attention is paid to this task, which involves mediating between filmmakers and the audience. And yet the way in which short films are compiled to form a programme and how they are then presented plays a vital role in their acceptance, their reception and ultimately their success.

While in the fine arts scene intense deliberation goes into putting together exhibition concepts, hardly any deep thought or analyses are devoted to this task in the film sector. The following discussion attempts to make a contribution to filling this gap. Various programme models and curatorial strategies will be presented. Due to the broad scope of this topic, the article will be published in two parts. In this first part, we will look at short-film programmes at festivals, and the second part will deal with the potential of short films in cinema programmes.

Festivals are today the primary platform for the theatrical release of short films. Historically speaking, film festivals are annual events of national importance designed to present each year’s film production to the public and to give the film industry an overview of what is on offer, while at the same time testing the critical and audience response to as yet unlicensed films. This description no longer really applies, however, because the proliferation of festivals today in many countries detracts from their function as a showcase, and changing economic conditions are undermining their role in the market.

For short film, this has already been the case for quite some time. Only in the 1950s and 60s was there a significant market for short films in the traditional sense of film deals being negotiated, or at least initiated, at festivals. But even if short film festivals no longer act today as marketplaces, that doesn’t mean that no money changes hands and no sales are made. Still, the many ways in which the films are monetized, for example for purposes of entertainment, information, education, culture, public relations or advertising, are too diverse to be covered by a single festival.

Festivals take this diversification into account in their concepts. While small, regional short film festivals are forced for capacity reasons to focus on certain categories, genres, themes and target groups, large-scale professional festivals fulfil several functions at once, but in parallel sections of the programme.

As soon as various target groups are addressed, consideration must be made of their respective viewing habits, working methods and needs. Festival sections such as film competitions, film markets, thematic programmes, retrospectives, exhibitions, workshops, seminars and discussions must be designed according to different programme models. For festival programmers, these sections differ mainly in the degree to which intervention is required – on a scale ranging from passive compilation to active programming to curating in the strict sense.

Due the increase in curatorial tasks, there have been some function shifts at short film festivals that can also be observed in the meantime in the segment of feature-length films. More and more film festivals derive their importance from the presentation of quality films that have nary a chance on the market. They thus serve as alternatives to cinematic release. Given the impoverishment of the cultural cinema landscape, festivals are now the only public presentation platform left for many artistically significant films – whether short films, long documentaries or fiction films. These are challenges that festival organizers must respond to by means of appropriate programme models.

Competition programmes

Competitions have historically been at the heart of every film festival. They were what prompted new festivals to be established and are still today part of their core business, even if they now make up a smaller share of the overall programme. There are still good reasons for their central position and relevance. In competition programmes, a wide range of works can be shown, with the chance of making new discoveries. In addition, competition programmes provide an opportunity for the participating filmmakers to communicate and socialize with their audience that is not created by any other programme segment or model. They are vital to what visitors perceive and value as the special festival atmosphere.

The organization and design of competition programmes is based on a fixed procedure that differs only slightly from festival to festival. The following steps – submission, selection and programming – and their particular features are typical at all short film festivals:

• Submission – open access

In response to a public invitation, filmmakers/artists decide to submit their works to the festival in order to participate. Access is therefore open and not by targeted invitation or selection, as is the case with curated programmes or exhibitions. The only restrictions are formal ones – having to do, for example, with the year of production or the length of the film.

• Selection of an exclusion and jury procedure

By excluding certain films out of the pool of all submissions, a shortlist is created of films that have been nominated by at least one member of the selection committee. All films on this shortlist are then discussed by the selection committee. This is followed by a voting procedure according to agreed rules that differ from festival to festival, leading to a decision on which films will be included in the competition programme.

This process is similar to the work of a panel of judges. In reaching the final decision, considerations regarding the balance in the overall programme between countries of origin, gender of the filmmaker or film genre may play a role as well as the thematic topicality of the films. But the primary standards applied are those of film criticism. In other words, quality judgments must first be made on the individual works.

This criterion already distinguishes the competition programme model from curated programmes. There is no thematic leitmotif in a competition. Instead of invitation and inclusion, the film selection is based on submission and exclusion.

• Programming – requirements specific to short film

In contrast to feature film festivals, in which programming is limited to the scheduling of screening times and festival days, short films are subject to a further programming step, which means additional intervention by the organizers. The individual films, which are to compete on their own merits, are bundled into programmes in which interactions in the reception of the films are inevitable.

For this reason, in the interest of the individual work, programmers should remove themselves as far as possible from curatorial practices. Contexts that charge the film with a particular meaning or suggest a certain interpretation are thus to be avoided. Ideally, a good competition programme is a compilation of single works whose individuality and intrinsic value remain recognizable and are rendered discernible rather than being subordinated to a curatorial statement.

Programmers should instead allow room for interpretation and contextualization outside the screening and thus delegate these functions to the festival participants. This interaction ensures productive tension and is another element in constituting a specific festival atmosphere, which differs from a visit to the cinema or a curated film lecture.

Curated festival programmes

There was a time when curated film line-ups at festivals were eclipsed by the competitions and other events, serving as more of a supporting programme. Today, however, they are increasingly coming to the fore in the form of retrospectives, tributes and theme-based presentations. At many festivals, curated programmes now enjoy an even bigger share in the programming than the film competitions.

What is noteworthy first of all is the diversification of the types of festival programmes being offered. This applies to both curated and non-curated festival sections. One example of the latter is the fragmentation into parallel competitions for films made for children and young people, or those by up and coming directors, as well as short-film competitions being held at feature film festivals. Separate competitions might also be held for specific genres, or even for certain financing and film production models (low budget, crowd-funded, mobile films, drone films etc.).

Further subdivision and diversification into sub-competitions within an already well-differentiated festival framework can itself become a curatorial act if quantity gives rise to changes in quality. This can even be the case when the resulting programmes still follow the competition model.

Also worthy of note is the growing desire among festival-goers for more contextualization. This need for mediation and explanation of contexts, but also for greater clarity – combined with diminishing curiosity about the unknown – inevitably pushes the organizers to undertake a curatorial upgrade. Ultimately, festivals are then threatened with a kind of biennialization. This development is currently difficult to prove, because, in contrast to Curatorial Studies, the field of Festival Studies is still in its infancy.

Festival makers are faced in their capacity as cultural mediators with the challenge of weighing which programme concepts are appropriate and meaningful for the achievement of their objectives. In practice, they assume a dual role as both programmers and film curators. What they choose to call themselves is quite beside the point as long as the description is not misleading or used merely to confer a higher social status. This status has also changed, however, now that the first wave of the curator hype (on this hype, see The year of the curators) is over and curating has become a field of study turning out many – possibly too many – specialists into what is a limited job market.

As film festivals do not have sufficient staff to professionally handle all potential programme areas and topics, and because they work only intermittently as time-limited events, they often enlist outsiders to take on curatorial duties. For the most part, they hire freelance curators who specialize in a particular subject area, are self-employed and thus are in command of their own time, and who often work internationally.

In contrast with the art field, freelance work is the rule in the film sector, apart from the classical curator working in a film museum or the curatorial tasks taken on by cinema operators. Film curators were also once brought in by cultural cinemas back when they still had the financial means and funding to do so. Typically, these were people who pursued several occupations and had established a reputation in a particular historical or aesthetic film niche, or people who represented a special film scene, often abroad, and who took their film programmes on the road from cinema to cinema.

Today, freelance film curators are trying to gain a foothold in the art sector, but still work mostly at festivals. For this reason, their working methods have a strong influence on the form taken by festival programmes. We can roughly distinguish between author-oriented and theme-oriented curators. Their approach to curating falls somewhere on a scale from minimum to maximum intervention in the intentions of the artists and the integrity of the works.

Theme-based curators share their knowledge for the purpose of conceiving programmes on historical, cultural-geographical, social or political issues. Their work is strongly dominated by research. The aim is to discover appropriate films from a field that has not yet been staked out and to put them together in a context in order to plausibly communicate and express a certain thesis or curatorial statement. This tends to be an open form of selection, which is very similar to programming. Such programmes document states of affairs, discourses and processes. In this way, they are able to convey social, political and cultural content and put it up for discussion.

At the other end of the scale are author-oriented film curators who work according to the principle of a database in which they have registered important works and authors to which they refer again and again. Their approach is diametrically opposed to that of the programmer. Such film curators are seldom seen at competition programmes at festivals. The more the competitions remain uncurated, the less interesting they are for such curators, who search in vain there for a consensus or a context. Their working methods are not based on an open search and making discoveries but rather on forging and maintaining good contacts with filmmakers and artists in the scene they move in. This form of presentation has in fact only been made possible by the rise in appreciation of the auteur film. The advantage of the method is a clearly defined and easily identifiable contextualization that promises to breed great consensual acceptance on the part of the audience. The downside is that – as in branding – it takes constant repetition of the artistic positions and styles to generate attention and to prevail over other works. And this in turn can lead to no new names ever being entered in the above-described curator’s database, with only the peer group and the same audience segment being addressed over and over again.

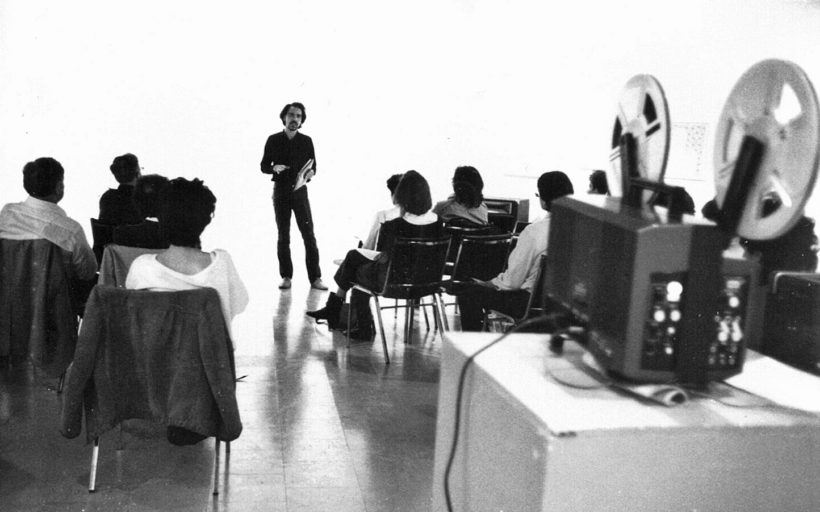

The politique des auteurs lets us segue nearly seamlessly into the art world. The auteur approach is compatible with practices in the art sector and has developed accordingly – with the result that curatorial strategies that are controversial in the art sector have managed to make their way into the world of film festivals as well. Cases in point are the star curator system or the phenomenon of the curator as a meta-artist. To cite a concrete example (one I myself have experienced ;-), an up-and-coming curator presented in the auditorium of a prestigious art institution a film programme garnished with wordy academic theories and presenting films displaying a style that is currently enjoying a hype. In order not to interrupt the curatorial flow, the titles and all the credits of the individual short films were omitted. Upshot: “The Curator is Present – The Artist is Absent” (text panel in video portrait of Hans Ulrich Obrist by Marina Abramovic).

Areas of tension and convergence in the film and art sectors

The younger generation of film curators takes its cue more and more from role models, practices and curatorial methods in the art sector. Conversely, few attempts have been made to date to reflect theoretically on what is involved in curating films or to conduct the requisite research. In Curatorial Studies, the “exhibition” of films still plays a subordinate role. Due to the temporal nature of the medium of film/video, curatorial models taken from the art world, which is predominantly occupied with exhibiting objects, are difficult to translate to film.

Film festivals with competition programmes can most readily be compared to art fairs. Art fairs are not curated exhibitions but events at which the latest works of selected artists are presented to the public and potential buyers. Traditionally, the task of art fair “programmers” consists in selecting galleries and determining the right spatial arrangement and staging to ensure that adequate attention is paid to the individual works of art. As with competition programmes at film festivals, this task of selection and arrangement is usually delegated to a committee.

Nevertheless, an erosion of these principles is in progress not only at film festivals but also at art fairs. Many large art fairs now have sections with curated exhibitions that are grouped around the market-oriented core. At Art Basel, for example, the main “Galleries” section (art market) has already been joined by two platforms for curated exhibitions (“Feature” and “Art Unlimited”). More and more of the other art fairs as well are allowing galleries to curate their sales stands and present the works in a museum format.

Analogous tendencies can be observed at film festivals. Film rental agencies and distributors are thus increasingly curating their trade shows. And once film markets are curated, the last stronghold of curator-free programming territory at festivals will have been taken!

Reinhard W. Wolf

(Programmer and curator)

Coming soon, Part 2: Short film in the cinema programme

Sources and links:

www.on-curating.org/

http://www.filmfestivalresearch.org/

The year of the curators – A reader’s digest of a mega-trend