Gudrun Krebitz Makes Experimental Animation Films – A Portrait

ECHODROM, 2022 © Gudrun Krebitz

“Are you afraid you’re not actually here,” asks a resounding voice in Gudrun Krebitz’s latest work “Echodrome” as the water ripples and splashes. There it is again – the ‘you’. A hallmark of Krebitz, a word that is at times a dialogic reassurance of the self, often addressing some metaphorical counterpart, or mostly directed at the potential audience.

“Everyone likes to be meant, to be addressed personally – to that extent, I like using ‘you’ and do so deliberately.”

The ‘you’ can also work well as a leitmotif, however, permitting us to feel our way through Krebitz’s worlds, sensing them visually. For these worlds are often opaque, indistinct, blurred, fantastically magical – we have never encountered them in this form before. They are neither narrative films nor thematic pieces, but rather experimental-associative works, yet ones that refuse to be placed in conventional experimental-formalistic pigeonholes. This is so because Gudrun Krebitz works mainly with her own voice (one exception being: “I know You”), often even assuming the role of the protagonist herself, and thus she also invites us to have an emotional-subjective exchange. And, apparently, many people feel drawn to Krebitz’s ‘you’, as though it is them she is addressing: Gudrun Krebitz’s films can be viewed at festivals across the globe; for “Achill”, her graduation film at the Film University Babelsberg KONRAD WOLF, she was awarded the Golden Horseman at the 2013 Filmfest Dresden, and for “I Know You“, the Grand Prix international at the 2010 Tampere Short Film Festival.

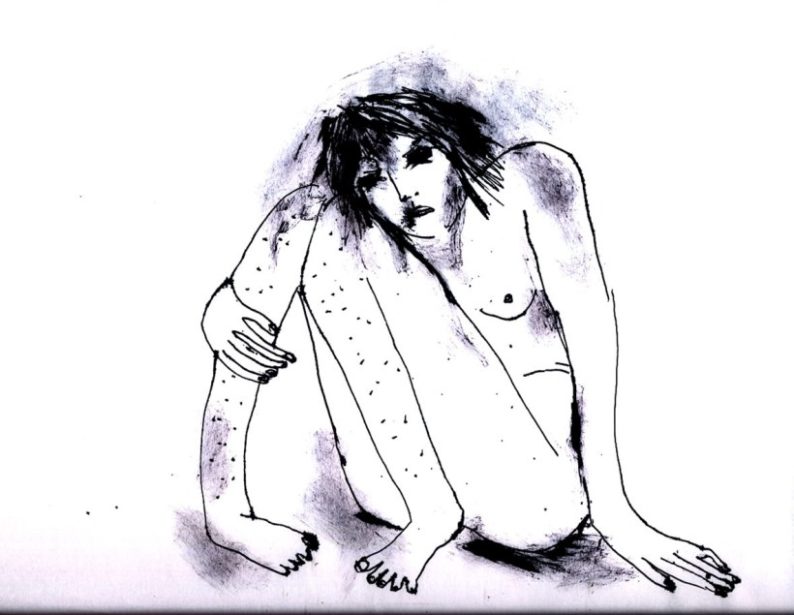

I KNOW YOU, 2010 © Gudrun Krebitz

In “I Know You”, the ‘you’ is already part of its title. Here it presents itself as something that cannot be mentally dismissed or put in a box. Or might the ‘you’ really “just” be the fear of not being able to belong, even if we do not want to belong anyway? In any case, the sketchily drawn character is constantly being trapped, with its own dancing legs transforming themselves into a huge spider clasping it tightly. Later on, the character even shoves other little arachnids into its own mouth. “The lies I ate them all,” says the distorted voice of Lola C. Bohles (one of the rare occasions when is it not Gudrun Krebitz’s own voice). The film was created without any attempt at form, message, or plan whatsoever. Nor was a synopsis provided. The associative, poetic text fragments seem to match this: They are breathless notes scribbled down in a rush on paper. “I Know You” is drawn on paper just like her second film “Shut Up Moon” – while with her 2012 film “Achill”, this minimalist style, as well as working with a sheet and a pencil, gave way to a downright obsession with the filmic material: Krebitz makes the film camera part of her creative process here, shooting herself and a bathtub, with drawn elements being added repeatedly to the images, together with painting on the film material. And for once, Gudrun Krebitz makes the ‘you’ – who is addressed gently – almost tangible, accessible, by transforming it into a romantic counterpart. A counterpart that she approaches through the fuzzy blur, or even through rose-tinted glasses, and which she then contrasts over and again with images that are even in focus at times. Yet here, neither the visually nor indeed the linguistically captured blurring represents a metaphor or a stylistic device: Gudrun Krebitz is very near-sighted – and at times she prefers the dim blur in which the world then appears to her. During the artistic process, her near-sightedness is not her Achilles heel, but rather a strength or a superpower of a somewhat different kind. One she has decided not to have treated.

ACHILL, 2012 © Gudrun Krebitz

Another superpower is her fearlessness when facing a “blank sheet” of paper, a fear she simply does not know. She says that she has always drawn. Always, never stopping through all the highs, lows and stages of her career. Drawing also provided an anchor for her when she grew up with four siblings in Graz, before quitting school at 15 and moving out. A break that seems incredibly hard when viewed from the outside. When asked about this, Gudrun Krebitz considers briefly: “Yes, in retrospect I can definitely say that this really was quite a hard break, because I was still even a child then. But at that time, I definitely thought I was an adult.” Krebitz enrolled for a year in the Vienna Art School, then began – and completed– an apprenticeship as an illustrator at a vocational school. Following this, she moved to Berlin. She completed several traineeships and then began studying at the Film University Babelsberg KONRAD WOLF – accepted onto the study course without the required school-leaving certificate as one of the few “special cases” permitted to attend the university because her professors, including the recently deceased Gil Alkabetz, recognised her unique talent and abilities. Here too, drawing proved to be a constant for her, although she did not plan on becoming a “filmmaker” at the end of her studies. Letting herself be defined by the term filmmaker represents a constriction for her, yet Krebitz also regards it as being an imprecise one especially, because it presupposes some final intention; whereas in fact she often does not know at all when drawing or writing whether a film will emerge from this:

“Basically I’m not a filmmaker, I just make films.”

Perhaps her fearlessness when faced by a blank sheet of paper is due to the fact that, unlike many other animation filmmakers, she does not plan in advance using storyboards or animatics. Quite the opposite. Her creative process is just as associative and wild as its potential reception. And doing so, Gudrun Krebitz completes almost all of the work herself, including even the soundscape level by now. Only the mixing is done by Marian Mentrup, who was already responsible for the soundtracks on her first films. When they began working together, it became increasingly clear that the dummy sounds Krebitz would insert as placeholders, so-to-speak, often functioned better than the compositions subsequently added. Yet for that, Mentrup continues to be one of the first persons to see her films and provide important input.

Such lone work can at times also benefit from the outside world, as Gudrun Krebitz experienced during her second studies at the Royal College of Art from 2012 to 2015 especially. A time in which she made some very close friendships. For Gudrun Krebitz, 2022 has proven to be a year brimming with encounters from the outside world – she was a stipend holder in April and May in Venice, and this October she is in Sweden, completing her International Film Residency in the Uppsala region.

ECHODROM, 2022 © Gudrun Krebitz

The visual heart of Gudrun Krebitz’s films consists of her drawings and paintings, which have become even more detailed and colourful since “Echodrome”. When drawing and painting, she works with all possible water-based paints, such as gouache and acryl for instance – and, if in doubt, everything that she can smudge and rework well not only with the brush, but also with her fingers. Krebitz is happy to leave “mistakes and flaws” in place, erasing some aspects and making others visible. What is striking about this: In “Echodrome”, there is rarely an image that corresponds to a classic expectation of animation images, flowing sequentially into each other. Gudrun Krebitz comments on this with a shrug of her shoulder, yet also quite drily:

“That’s how it works in ‘real’ life as well, doesn’t it?”

In addition to the painterly level, there is also the live-action level, created using video footage shot on a mobile phone or a simple, light hand camera, or even a Super 8 camera at times. And she always has a notebook with her to jot down notes as required – even when nothing happens as such.

“Basically, I can’t even go out for a jog without realising that I want to write down something.”

And perhaps this is also the reason why the idea of taking a holiday and having a break from drawing, for instance, seems so absurd to her: She does manage to keep her professional and her private lives separate, but her areas of works do become fuzzy or overlap with each other. And there is material to be found everywhere.

Following this artistic collecting of the material, Gudrun Krebitz scans in the analogue visual material and edits is all in Photoshop, superimposing levels on each other. The voice and sound recordings, which often seem celestial, are then created and added during the editing. Although “celestial” is presumably not a term that Krebitz would choose – for this would again cement the separation between the mundane and the extramundane, the within and the without, the real and the imagined, which Krebitz would like to dissolve anew over and again. That several of her films are received as flights from reality is something that truly astounds her:

“They’re not about escapist worlds, or dreams.”

And then she laughs:

“I’m a documentary filmmaker. My films are the news. They show how I sense and perceive the world.”

And it seems that the CPH:DOX Documentary Film Festival, where “Echodrome” celebrated its premiere this March, agrees with this viewpoint.

THE MAGICAL DIMENSION, 2018 © Gudrun Krebitz

The artistic distinction between the “real” and the “imagined” is an ongoing theme in Krebitz’s films. This is perhaps most explicit in “The Magical Dimension”, in which Krebitz’s voice proclaims in a manifesto-like tone (and of course at the same time not manifesto-like at all): “You can always be at two places at once. Did you know? The real world and the magical world, or if you prefer the term: The magical dimension.” We hear a light switch clicking and the previously gloomy hallway of a house party suddenly seems to be bathed in a dim red light. Krebitz says:

“The still drawings represent my insistence that this is the reality. That these things exist. And if I have a piece of paper with a drawing on it, that’s proof of its existence.”

That such visual worlds do not, at some point or other, slip into something we might call “enrapturing” or “romantic” is also due to the fact that Krebitz frequently switches from poetic fragments into everyday language, or from a serious tone of voice into an ironic one. Such as for instance in “The Magical World” when she comments drily: “You don’t believe in a magical dimension? Allow me to make my surprise face,” and then the camera reveals the hand of a stone statue in close-up that of course remains unmoving, with no expression of surprise on display. A wink of an eye, subtle humour. Likewise, her latest film “Echodrome” (working title: “Nighttime at the Well”) also has such quiet, humorous moments. And it derives a lot of its energy from water, which plays a role in many of her films, just like the ‘you’ does. She loves water in all its forms, as Krebitz mentions in conversation. The rippling and the murmuring, but especially how we humans connect ourselves with the element of water.

Time and again, Gudrun Krebitz confronts her autonomous working method and her analogue, fragmentary visual worlds by posing one of the most crucial questions within the animation industry: Is her work animation, or not? For Gudrun Krebitz, this is actually a joke question:

“It’s completely clear to me: As soon as the camera is stopped and manipulation occurs, it’s animation. As soon as a still image encounters a moving image, it’s animation.”

But pre-set production processes and predetermined animation phases are something Krebitz avoids in her work as far as possible. Because:

“Basically, the animation threatens my still, non-moving drawings.”

As an expression of her freedom. Since she regards these processes and structures as being restrictive, she also does not lay down a pre-defined set of rules to the students who can by now study the basics of “experimental animation” under her at the Film University Babelsberg KONRAD WOLF. And especially: No one is required to explain themselves. Perhaps this is also the reason why Gudrun Krebitz herself continues to search for the limits of the filmic, the cinematographic, with her own films, and regards the screen framing as a limitation on her associative visual montages that demand so much and can never be grasped (in their entirety). And that, even though by now, like many other independent filmmakers, she has to submit applications for film funding and, doing so, is also repeatedly requested to “incorporate” herself and her efforts into some specific contextual and visual form.

In order to accord her own creative process another freedom, by now Krebitz has also become involved in the field of installation art (which is also struggling with its own categorisation constraints). Right now, she is working on a mobile, walk-in 360° installation for instance, which can be experienced in both Vienna and Graz in 2023. It explores one of Gudrun Krebitz’s favourite themes, which is counted among the main protagonists in her films: The moon and outer space. She does indeed have a moon fixation, says Krebitz, and during her studies she really did work at night mostly. This fixation is related, on the one hand, to the visual components – or in other words, the actual depictions of the moon and outer space in science fiction films – as indeed to the philosophical aspects:

“That there are things out there that are so much bigger than us is something that really reassures and comforts me.”

EXOMOON, 2016 © Gudrun Krebitz

This fascination can already be found in “Shut Up Moon” and then subsequently in “Exomoon”. For the new 360° installation, she conducted research beyond her own daily routine and visited a hobby astronomers’ club in the Berlin planetarium. By expanding her animations into a physical space, perhaps the possibility will arise of being able to delve into Krebitz’s works in yet another, truly different way. By being able to also encounter her sensual-bodily works in a physical-sensory manner, rather than analysing and wanting to understand some rational filmic elements. Which would presumably be completely to Krebitz’s liking.