COMFORT STATIONS, 2018 © Ojoboca

At one and the same time, Ojoboca (Anja Dornieden and Juan David González Monroy) make both more and less than “short films”. More to the extent that, in addition to shorts, they also create performances and installations, are currently working on their second feature-length film, and texts of an idiosyncratic literary quality accompany almost all of their moving-image works. And less to the extent that they deliberately undermine our expectations of conventional cinematic forms and genres, through to the idea of individual “works” in whose place a more comprehensive practice occurs that enacts and captures cinema as an institutional and psycho-physical space: “Orrorism, a simulated method of inner and outer transformation.”[1] It seems that it is not the artists/authors who energise and propel their films, but rather the film machine and the narrative, illusionistic, manipulative power with which it takes possession of us, guiding us and leading us astray.[2] In this sense, it is only logical that Dornieden and González Monroy also camouflage their authorship with the conjoint label of “Ojoboca”. Based on Pasolini’s idea of the camera as an “occhio-bocca” or “reality-eater”, the term also somatises the moment of the film experience: as seeing that devours and permits itself to be devoured.

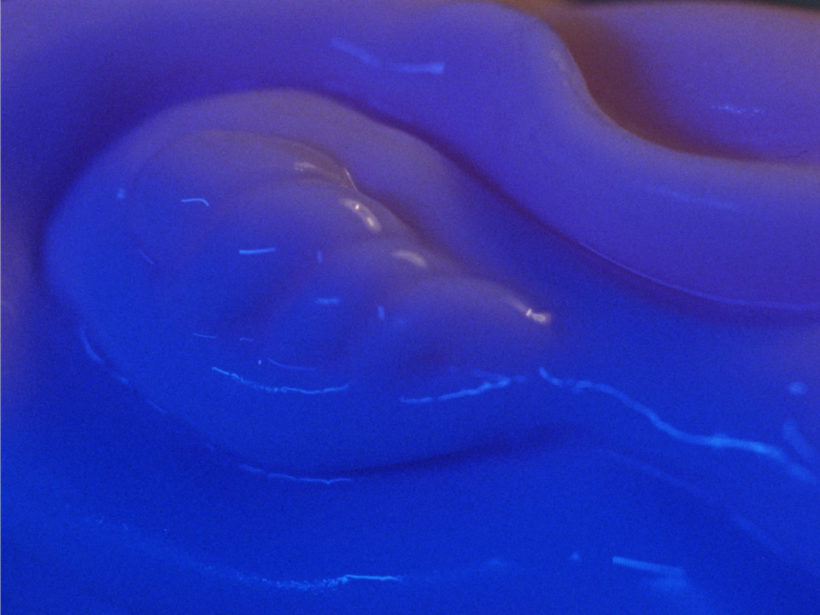

The films of Ojoboca portray our relationship with the (animate) world as a drama of closeness and distance, in which fiction and reality, the found and the fantasised, are always interwoven. Comfort Stations (2018), a film which, according to its description, was found and identified as a possible component of a psychological test, interlinks moments from nature films and the fascination of events never-before-seen-like-that with a sound collage that bounds erratically between differing versions and elements of the jazz classic Dream (When You’re Feeling Blue). We see macro shots of unspoiled nature – dew-covered plants, tadpoles, snails – whose closeness attracts at times and repels at others. Likewise, a brownish, blubbering “primordial ooze” conveys a sense that the life being shown here provides no cause for romanticisation. The motifs vary over the course of the film and progressively become incorporated by it: As a backdrop for plumes of smoke billowing colourfully, or as a spectacle in its own right, such as a dandelion being devoured by fireworks, the forest floor in stroboscopic light, or the “primordial ooze” mutating into brightly glittering lava. Landscapes become transformed into crime scenes, while the soundtrack slows down ominously.

THE SKIN IS GOOD, 2018 © Ojoboca

Close-ups of human skin, of eyes and mouths, in black and white, rupture the nature shots, perhaps so as to evoke the place in which the sensory touching of and distancing from this world occurs. In a manner similar to The Skin Is Good (2018), at one and the same time the skin is desired and feared as a place of transition, as a porous contact zone between the self and the world. The life that the film arouses is clearly ambivalent. While depicting the fragility of all living things, at the same time it reveals itself to be that which is capable of according and prolonging life: The medium in which nature still continues to exist even after it has ended. The film concludes with an ecstatic dance by viscous matter, in which everything is absorbed and everything is possible.

INSTANT LIFE, 2021 © Ojoboca

Likewise, their latest film Instant Life (2021) is, as mentioned by its three authors – it was created in cooperation with Andrew Kim – not an original work, but rather a shot-for-shot reproduction of a compilation film whose individual parts refer to a precursor of the same name. One component of all the films consists of an irresolvable riddle – one that already seems to begin in this convoluted backstory. Instant Life evokes new life in its predecessors – three lives that are, however, dramaturgically interrelated. We see crystals and cellular structures growing and decaying, storms looming and fog swirling, bleak non-places and glistening salt lakes, found or created with analogue effects, and colorised using light and filters. In this supernatural cosmos, the growth is just as excessive as the decay, with both of them merely kept in check through cunning. Progressively, the artificiality of the scenes is revealed, yet the more obvious the tricks and deceptions become, and the more emphatic the warning is of their corrosive power, the more enticing it seems to believe that the illusions and contradictions in this visual, textual and vocal narrative are true, and to follow them.

INSTANT LIFE, 2021 © Ojoboca

Instant Life is a performative instructional film about the creation of artificial life and the precarious conditions under which it exists or passes away. At the same time, it is a study on the psychopathology of the film machine, whose perversion exposes us to an irresolvable riddle. And in the alchemistic logic of Instant Life, both of them come together. The artificial life of which we are speaking here is also the life of the film. This consists of the found or fictional places and beings invoked in the film, but also its own form of existence in precarious film exploitation cycles and disturbed habitats. Instant Life also recounts its own creation from fragile and “handcrafted” materials, from almost nothing and from everything that Hollywood negates or denies.

The unique haptic quality of Ojoboca’s films is also due to this sense of their being “handcrafted”: by working with 16mm film and in self-organised analogue film labs.[3] Despite (or thanks to?) the powerful physical presence of the material, often the films cannot be placed in a specific time, as though they are deliberately seeking out an indefinite moment between the past and the future. And this is where the texts situate them that accompany most of their works as descriptions. They allude to and speak of found film footage and text material, together with the circumstances under which the artists came to possess them, of historical events and their revenants, of (pseudo) scientific experiments and séances that often branch off labyrinthine-like into further “sources”. They assert to historical depths and causal connections, and lay trails with a decorative flourish. They adamantly refuse to have the last word about a film and its authors, and thus they are the antithesis of conventional film descriptions. When the artists attend a screening, the corresponding text is read aloud prior to the screening and thus becomes part of the cinematic event. Here too, nothing is explained as a ritual transition occurs instead: Whoever takes part in this declares themself ready for everything that follows. The experiment can begin.

HELIOPOLIS HELIOPOLIS, 2017 © Ojoboca

Above and beyond the texts, the films themselves also have their own idiosyncratic way of addressing us. Quite a few of them speak to us directly. At times, these voices let themselves be identified or are assigned to characters, yet often they are just merely voices – anonymous, bodiless and faceless mediums of invocation and interpellation. In Heliopolis Heliopolis (2017), a legendary prehistoric model city of the same name – an optimised double of the real Heliopolis – forms the background to its speculative filmic reconstruction. Two computer voices alternately address a “you” (or us?) and instruct it to read texts aloud that appear on colour charts on the screen before us. Differing definitions of “inside” and “outside” alternate with shots of burning motif-candles, partly rotating on their own axis and which melt in fast motion before our eyes. As the contours of the things become fluid and the two voices become increasingly interlaced, the definitions also lose their preciseness and become more and more lunatic, as though they are mutually deforming, doubling, gobbling up and excreting each other out again.

In this filmic exercise of the imagination, the fictive historic city as a meaningful cosmic construct, reflected in the ordering system of language with demarcations, inclusions and exclusions, is not newly erected. Instead, it is disassembled a further time in a free play on absurdity. And the more exactly we follow the film, subjecting ourselves to its instructions, the more the indications and points of reference slip further away from us. Who exactly is speaking here? And who is listening? The inside and the outside keep changing sides, imposing upon each other, including and excluding us at one and the same time. This “exercise” seems like the perverse copy of the direct rapport that is commonly assumed between a film and its audience in a cinema situation; like the attempt to clutter the conventional language of cinema so long with the absurd and the abject until it implodes. And thus we are possibly not the subjects of this experiment at all, but rather the film itself is?

THE MASKED MONKEYS, 2015 © Ojoboca

If these works are also understood as a commentary on the experimental-like in experimental film, one capable of pivoting between science and séance, then The Masked Monkeys (2015), for instance, also relates powerfully to the documentary tradition in terms of its form and content. The film is based on material that was shot as part of research on the traditional dressage of masked monkeys in Indonesia (which is banned in the meantime). In coarse-grain black and white shots, the film shows human trainers and their animal performers both at work and during their time off, accompanied by a soberly spoken commentary, the style of which immediately brings to mind early anthropological films. While the commentary is initially descriptive and analytical – as a contextualisation of “foreign” cultural practices – it changes its tone almost imperceptibly over the course of the film, culminating in a vision of universal harmony and redemption at the end. This gradual change in the perspective of the female voice-over narrator is reflected in a semantic drifting that the text generates between the performer and the role, the historic role model and its current embodiment, the human and animal “master”, or the (post) colonial and the artistic mastery. This oscillating movement is expressed visually in a hypnotic five-minute flicker sequence at about the middle of the film – the close-up of a monkey’s face in a human mask. The Masked Monkeys conveys the ciné-trance state, with which Jean Rouch described his working approach,[4] from the producers to the recipients of images: A sense of being inside and outside at the same time in relation to the rituals of a foreign or alien reality, of becoming infected by events, one that not only questions the claim to objectivity of documentary images, but also the feeling of cultural distance or moral superiority in light of a cultural practice perceived to be strange and disconcerting.

A FLEA’S SKIN WOULD BE TOO BIG FOR YOU, 2013 © Ojoboca

The designation prefixing the film – “to inform and not to amuse” – also provides guidance to a further documentary project, A Flea’s Skin Would Be Too Big For You (2013). It centres around performers in a Chinese theme park who embody the occupants of an imaginary dwarf realm – the projection of a preindustrial ersatz paradise in communist China today. Of the latter, only momentary fragments appear, such as when during their free time the performers chat about their families and the towns they come from, often a thousand kilometres away, that they had to leave for the work. Otherwise, the film remains consistently in the dwarves’ entertainment territory, accompanying them to work in the park and on stage, or lets them perform dances, songs and presentations specially for the camera. The latent discomfort and unease that arises in us when faced by the staging of these socially disadvantaged persons before the camera is taken up and turned on its head with a twist at the end of the film. One of the actors says “Thank you” countless times directly into the camera – openly sometimes, doing so automatically or grudgingly at other times – and thus clearly indicates that this expression of thanks was ordered, and that specifically for us. We are being addressed as those whose presence made this staging possible in the first place. Thus, when we chafe at the filmic representation of a system that exploits marginalised life as a spectacle, we are already exposed as being part of it. In the protagonist’s reluctance, their final performance not only suggests a moment of refusal, but also a possibility of buying a piece of freedom from this system by exoticising one’s own otherness and turning it into a product.

The films of Ojoboca, whether created with a more experimental or documentary feel, develop a hypnotic suction that grasps our complete sensorial apparatus. Doing so, this is never concerned with mere immersion, with a passive submerging and dipping, but rather with the immediate experience of being implicated in or infected by the reality that the film machine permits us to see. It is as though they want to activate our antibodies so that we stay alert to and wary of this machine that is only pretending to make common cause with us.

[1] http://ojoboca.com/about-ojoboca/

[2] Dornieden and Monroy titled a program series for the European Media Art Festival 2021 “The Unpossessable Possessor”, in which they investigated the obstinacy of the cinematic apparatus, its actions and intentions, desires and aberrations. See https://2021.emaf.de/sektionen/

[3] Both are members of the artist-run film collective LaborBerlin.

[4] see Jean Rouch, Ciné-Ethnography, hg. von Steven Feld, Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press 2003, S. 39.

featured image: COMFORT STATIONS, 2018 © Ojoboca