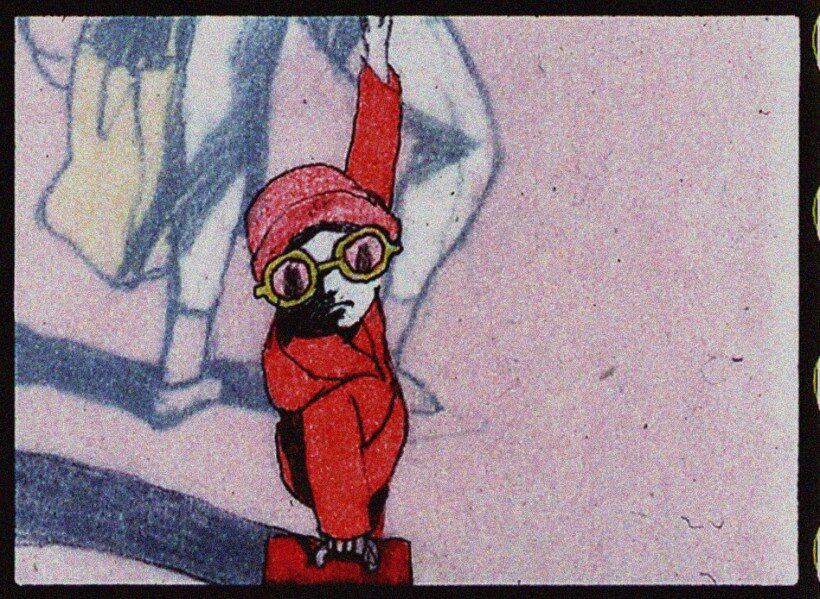

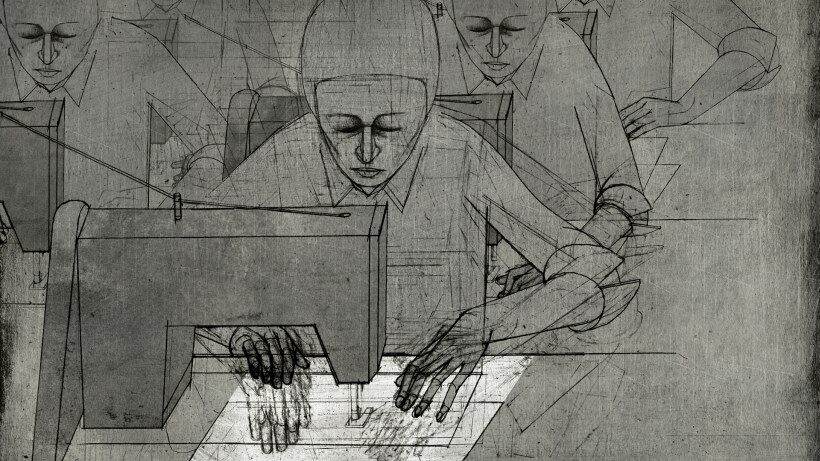

THE WAITING (2023) © mobyDOK, Volker Schlecht

An image that fits to a T – what is that exactly? And what precedes it – perhaps another image, one before the inner eye, or merely just a vague thematic hunch? These are questions that arise quickly when you explore and engage yourself with Volker Schlecht, who pivots back and forth between the moving and the non-moving image: The animation filmmaker, illustrator, drawer and Professor of Graphics Principles at the Anhalt University of Applied Sciences in Dessau is travelling around the short film circuit right now with his animated short THE WAITING (2023) Having celebrated its premiere in the Berlinale Shorts section of the 73rd Berlinale, the film’s second stop, having celebrated its premiere in the Berlinale Shorts section of the 73rd Berlinale, was this year’s FILMFEST DRESDEN – International Short Film Festival, where it went on to win the Golden Horseman Best Animated Film in the National Competition. THE WAITING deals with the extinction of a rare species of frog – and doing so it also reflects on global interdependencies and commonalities between the species, including their gasping suffocation. Yet for that, the film is also an elegantly animated homage, one that resists simple answers and ponders this extinction instead – and, in terms of its consistency, is an inspiring animated documentary. This is a quality that THE WAITING has in common with its predecessor film KAPUTT (Broken, 2016), which won numerous international awards, including the main prize at the Stuttgart International Festival of Animated Film (ITFS), as well as in the best short film category at Sundance Film Festival.

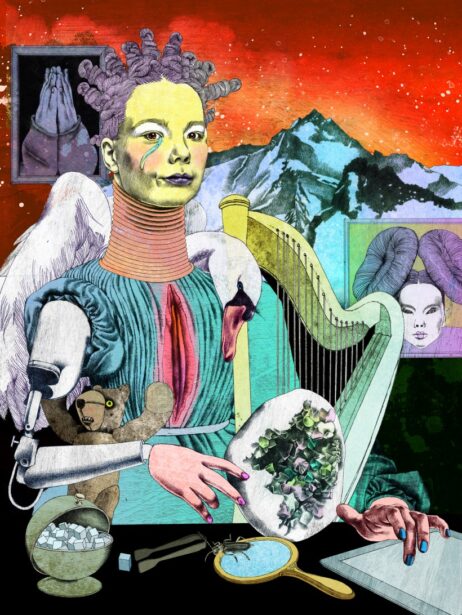

RUE ROSÉ © Volker Schlecht

The fact that by now his films are gaining recognition on an international level and he is becoming known to many in the world of short film as a filmmaker – although he is more than just that – is ultimately a biographical coincidence that could, of course, also be called fate. Volker Schlecht actually studied commercial art and graphics at the Burg Giebichenstein University of Art and Design in Halle. Eva Natus-Salamoun happened to be a Professor of Illustration there, who, through her role as a film director, had excellent connections with the animated film scene in Prague. She was the one who “opened up the world of animated film” for Schlecht, such as, for instance, by taking her students with her to Prague for a week once each year. This proved to be a proper enlightening experience for Schlecht, so that he ultimately decided to be the first person in his study year to complete an animated film for his degree studies: The graduation film RUE ROSÉ (1997), a matryoshka film that derives its energy from its rhythm, purporting to be the various gaits and walks of passersby. The Eastern European influence can be clearly felt in RUE ROSÉ: it is reminiscent of formative films from Poland, the Czech Republic and Estonia at that time.

The filmic production process was an adventure that he would not have dared to risk perhaps had he been aware of all the details involved: Without speaking a single word of Czech, Schlecht spent about six months in Prague, leaving Salamoun’s place only to go and work on the seven-minute film that he was drawing by hand in Studio Bratri v triku on the Barrandov. A massive project. RUE ROSÉ was followed by the three-minute work SONST NICHTS (2000), in which Schlecht plays with the perspectives and glances that a passerby casts at a fellow traveler.

Illustration for Musikexpress magazine © Drushba Pankow

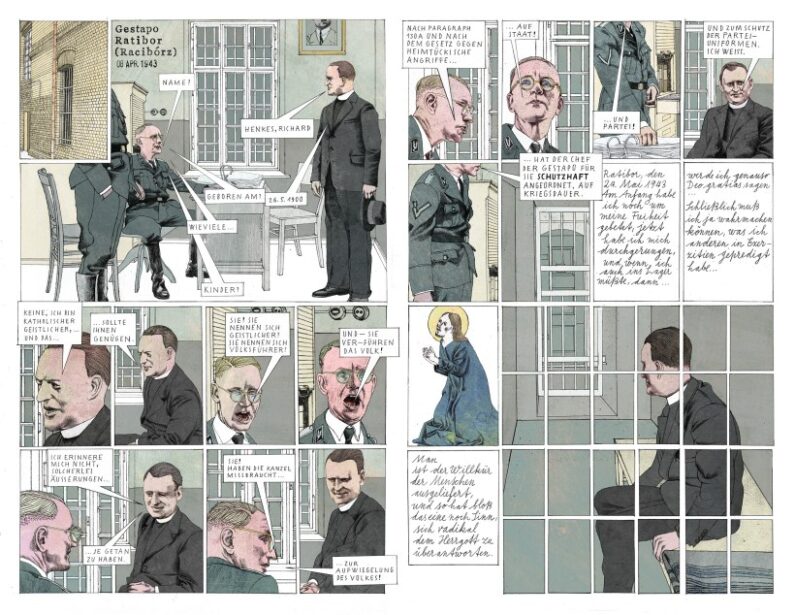

For Schlecht, the gaits and walk-cycles provide themes and even rhythm-giving stylistic elements – and they fit and work so well in the illustration medium, too, you could think they have always gone hand in hand. Yet in fact Schlecht first discovered illustration at a later stage through the work he has done together with Alexandra Kardinar, a fellow student in Halle. Calling themselves the Duo Drushba-Pankow*, their shared work and now well-known style began with an experiment: For one of their first projects – a double page in the first edition of the Freistil compendium of illustrations – both of them sat in front of a large white sheet of paper and then began drawing on the basis of the exquisite-corpse principle, with one of them drawing first and then the other one, without either of them knowing what would come of it. In the middle of and next to each other, above and alongside each other. In this way, a photorealistic style was created, in which one “does not recognize who has done what” – and that also works under a certain degree of time pressure. The co-creative process, which was analog at first, also functions in a similar manner digitally – with Kardinar and Schlecht randomly sharing the visual elements between them and subsequently assembling them together using Photoshop and coloring them. The basis for their work continues to be provided by photo references which, however, they did not slavishly adhere to, and instead turn them into their own subjects through omissions or additions. It is a style that is enjoying much popularity and being requested for numerous illustration projects, such as in the Psychologie Heute journal or Die Zeit newspaper, for instance. Schlecht knows this is a blessing, yet it is also a curse: even if both of them would like to try out something different, fundamentally they are being booked for what they are already known for. The extent to which they are ultimately able to deal freely with their referential material is, however, determined solely by the actual commissions. In “And When the Truth Does Not Destroy Me – Pater Richard Henkes in Dachau Concentration Camp” (a graphic documentary about the journey through life of the Pallottine Father Richard Henkes), it was clear that the photographs would not tolerate any changes, that the level of detail was urgently required to convey the authenticity of the resistance story being narrated. And with projects such as “Das Fräulein von Scuderi” they were able to improvise completely, which they then also did.

„Und wenn die Wahrheit mich vernichtet – Pater Richard Henkes im KZ Dachau“ © Drushba Pankow

By contrast in the field of animation, working this deeply with reference material is simply not a must, and instead, the focal subject matter provides the starting point together with the visual transformation potential of animation, as Schlecht says. With GERMANIA WURST (2008), the first short film that Schlecht drew digitally, he was concerned specifically with going through that process of transformation from A to Z in the sense of creating an associative chronology of German history over no less than 2,000 years. Essentially delivering an apparently playful exploration of the interrelations between differing conditions of state, systems, and political currents; the continuity of militarism and fascism. A German wurst mixture of topics that squeezes itself, or is itself squeezed, through the various epochs, German shepherd dogs included.

GERMANIA WURST (2008) © Filmuniversität Babelsberg Konrad Wolf

Volker Schlecht made GERMANIA WURST when he was a lecturing assistant at the Film University Konrad Wolf (2002 to 2007) before going on to teach fundamentals, animation and illustration at the Berliner BTK/University of Europe (2007 to 2020), where he was appointed professor from 2014. It was the first of three life stages by now when Schlecht has worked as a lecturer. A bread-and-butter job, yet one from which not only has he been able to draw much strength but also pass on his experience. Since 2022 he has taught the principles of graphics in the field of architecture at the Anhalt University of Applied Sciences in Dessau. A field in which he feels comfortable and unrestricted.

I did know all the other areas from the viewpoint of a do-er, but not from that of an expert, which I noticed especially in the comic field.

But despite this self-perception he has managed to teach himself much through his own lecturing work. These adaptation processes may perhaps not have been hurdles or inconveniences, but they have certainly consisted of “learning” contextual, curricular basics anew time and again, with him never being quite certain if he has mastered everything to the last detail.

© Volker Schlecht

When it comes to the principles of graphics in Dessau, by contrast, he is familiar with the material immediately, perhaps also because drawing dominates Volker Schlecht’s everyday life anyway – beyond the university, as indeed also beyond the shared work as Drushba-Pankow. Because for Schlecht, drawing freely represents a daily act, a necessity that at first “wants nothing.” There is always a sheet of paper lying around that he is working on, regardless of whether the iPad is placed beside it, or the monitor. And in fact, even the sheet of paper was preceded by a dried-out tea bag, on which Schlecht would draw with a ballpoint pen. He has already presented the “Tea Bag Series” that emerged from this, as well as other works, in the context of group exhibitions. The extent to which he himself has the ambition to also hold solo exhibitions of his work is something he does not know right now:

I am serious about being able to draw freely. But I’m under no pressure to prove myself here.

Schlecht began the drawings while working on KYRIE ELEISON (2013), a meticulous figures-from-antiquity animation. Not necessarily opaque, but far less accessible than his other films, KYRIE ELEISON thematizes Greek-Roman influences on early Christianity, interweaving religion with Mozart’s music. An Italian filmmaker would have understood it immediately, Schlecht explains, although he believes that the film is perhaps somewhat less accessible for central European and even German audiences.

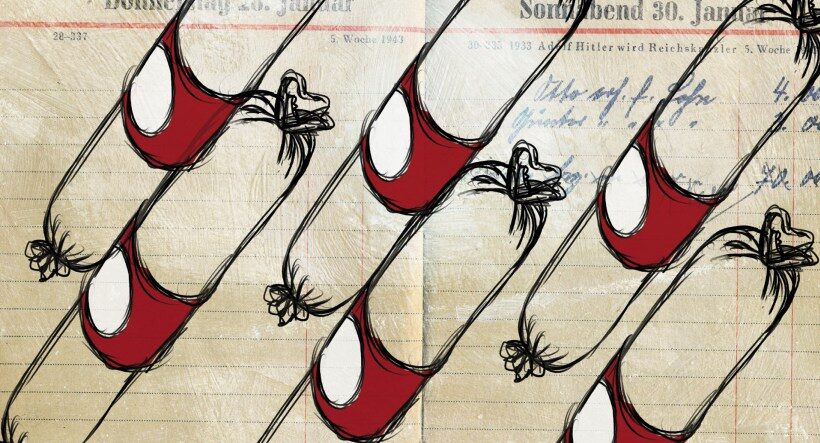

KAPUTT (Broken, 2016) © mobyDOK, Volker Schlecht

By contrast, Volker Schlecht’s best known film KAPUTT (Broken), one of the very few animated films ever to take the illegitimate state of GDR as its theme, is certainly intended for larger audiences. The basis for Broken, which Schlecht created together with the mobyDOK author and producer duo Max Mönch and Alexander Lahl, were voice recordings of former inmates at the Hoheneck Women’s Prison, which immediately shook Volker Schlecht to his core on the first listen. Here, he availed himself especially of the restricted space in the cells and the forced labor that have such a marked impact on the film, which Schlecht adapted analogously to William Kentridge by means of erased drawings. Doing so, KAPUTT (Broken) completely foregoes the use of talking heads that are found so often in animation documentaries. Solely through visualizing the ever-tighter spaces and structures in combination with the powerful fragments of memory, a claustrophobic insight into the grueling everyday life in prison arises.

For THE WAITING, on which Schlecht worked together with Alexander Lahl and Max Mönch yet again, voice recordings again formed the beginning – or rather the question, too, of whether Schlecht wanted to supply the visual world to these voice recordings. For it seemed abstract to him. But then he listened to the voice recordings closely, and he was immediately drawn to the enthusiasm of the researcher for her subject, the frog. The film was made – the first one in years – completely without teaching duties, between the lecturing period at the BTK and his appointment in Dessau. During the final phase, he also drew a lot on his iPad while travelling by train, and he gained a sudden insight doing so: It was the first time ever with his drawing that he did not have the sense of having to work “against the machine” in the digital space, or even “of having to work against its cleanness.” He realized he could use rotoscopy for the few hospital scenes, but he was only able to capture the frogs in their movements through his own drawn confrontations with them, with just a little naturalism being gained from YouTube references. And for the first time, he was reasonably satisfied and happy with the “onion skin effect” in the animation – with an image visibly peeling and emerging out of the next one, pausing, and making space for the one that follows. For Schlecht, this was also an homage to a favorite film of his, the classic PAS DE DEUX from Norman McLaren (1968).

The altered perception process that arises when working digitally is something Schlecht is keenly aware of. Thus, digital drawing and animation only saves time when you look solely at the work steps involved – yet through digital work, a craving for perfection arises that is, in turn, intensely time-consuming. For that, the trial-and-error principle, which goes hand in hand with digital work and is comparable to “chiseling away at a sculpture” or the like, can be great fun. Yet with illustration, his other major field of work, Schlecht certainly is worried about the risks of digital perfection associated with ChatGPT and other image generators. For graphic designers and illustrators especially who work using reference material, we can already ask the question of whether they will be replaced by a machine at some point. Yet for that: There is always the teaching context for Volker Schlecht, and of course his own free drawings. And then, thank God, there will always be his desire to work collectively as well to bring new films into existence.

* The name of the illustrator duo arose from a common reference to East Berlin at that time, one meant to be funny in nature, even if today Schlecht sometimes has doubts about how the name feels. Since the start of Russia’s war of aggression against the Ukraine, a clarification and explanation of the name can be found on the website.

featured image: THE WAITING (2023) © mobyDOK, Volker Schlecht