Birgit Hein was among the most important figures of avant-garde film culture in Germany and Europe. Along with her ex-husband and collaborator Wilhelm Hein, she led film into radical and uncharted territories, concerning herself unreservedly with the development, criticism and dissemination of avant-garde film. She started out collaboratively making films with Wilhelm Hein in the late 1960s which continued for nearly two decades and then made films on her own. She simultaneously established herself as a reference point for experimental film scholarship in Germany, worked as a performance artist, devoted herself to film curation in art spaces and underground film venues and taught at the university. She passed away in February 2023 at the age of 80, leaving behind a trail of pioneering accomplishments, singular in their scope and significance. In this article, I take a close look at Birgit Hein’s[1] work in the 1970s, a period which marks many radical and aesthetic aspirations in society and art, a phase where Birgit Hein (and Wilhelm Hein) almost single-handedly set the stakes for experimental film culture in West Germany.

Writing

Birgit Hein published Film im Underground in 1971[2] , the seminal book on experimental film, a first of its kind in Europe, which meant that in the male dominated experimental film world, she would have a rare recognition of her own (rather than as a subordinate to Wilhelm Hein). Birgit Hein was the sole author of this book and of all the key texts she wrote on the subject in the 1970s.

Writing and filmmaking as part of a unified intellectual endeavor was not unheard of in the first half of the 20th century, Jean Epstein, Germaine Dulac, Sergei Eisenstein, Maya Deren, to recall but a few names. However, it really gained prominence among experimental filmmakers in the postwar era, when it became apparent that meaningful discourse around experimental film was scarce. Some writers-filmmakers of note here would be Peter Gidal, Lis Rhodes, Paul Sharits, Hollis Frampton, Claudine Eizykman, Peter Weibel, and Valie Export among others. If one adds curation to the mix, this small group will dwindle further.

In the 1970s through her writings, Birgit Hein was aiming for a condensation of the history of avant-garde cinema, differentiated from variants of independent, political or alternative cinema in their formal rigor. While the emergent European new waves in the 1960s (French, German, Italian…) looked at the modern Hollywood films of the 1940s and 1950s for inspiration, both as the focal point for theoretical investigation (semiotics, psychoanalysis) and visual stylistics, it was obvious that avant-garde film needed to look elsewhere.

In the US during the 60s, Andy Warhol made films, Fluxus and New American cinema was consolidating through the decade, P. Adams Sitney had penned down his essay on Structural Film in 1969 (somewhat hastily), and Annette Michelson edited the special issue of Artforum on Film in 1971, the same year as the publication of Film im Underground. Michelson shared with Birgit Hein a vision for a history of experimental film that connected several developments in the 1920s to the 1960s. Though Michelson’s historical preference was for the Soviets, Dziga Vertov and Sergei Eisenstein, Birgit Hein oriented her attention towards the first three decades of 20th century when abstract, surreal or documentary films were made across Europe. This was a much more resonant context for Birgit Hein than erstwhile West Germany. She wrote as a filmmaker, valuing formal achievements in films (predominantly short in duration) otherwise unnoticed, and critiquing acclaimed films within journalistic and festival spheres. She dealt with concrete formal problems rather than abstract theoretical positions. The full scale of the theoretical and topical affinities in her writings from the period cannot be covered here though a few salient points are outlined below.

-

- A materialist framework: Film, rather than representing external reality, chooses to represent its own material reality and structural logic, film as the subject of film. (Der Strukturelle Film, 1977[3]).

- De-romanticization of art and film: No beautiful images (with pronounced painterly attributes). Denouncement of the romantic roots of artistic/authorial creation, ideas congruent with the post-structural thought (of Roland Barthes, Michel Foucault) on authorship. Exploration of non-art and non-composition as ideas drawing upon Fluxus.

- Politics and Avant Garde: For the Heins, politics is equivalent to active sociopolitical change and did not involve framing of formal problems (in process-based non-representational art) via consideration of leftist ideas (like Peter Gidal). Co-existence of leftist politics and experimental filmmaking was comprehensible only as a social condition (Avantgarde und Politik, 1976[4]). A reason for such a position could be that in West Germany at the time, direct expression of sexuality or nudity on screen was heavily censored. Experimental filmmaking of any kind was obviously incapable of registering decisive shifts in such social and federal attitudes.

- The influence of New American Cinema (NAC): Birgit Hein unabashedly acknowledged NAC as the pivotal reference point for filmmakers of the experimental persuasion (Film im Underground (1971). She is frank in her assessment of the intellectual gaps in European Film culture at the time when dealing with experimental film. She notes the singularity of the Knokke experimental film festival in the 1960s in Belgium vis-à-vis more traditionalist festivals like in Oberhausen.She however made it a point to devote necessary attention to Germanophone filmmakers with a formal edge, clearly understanding the dual challenge that faced them- to avoid being eclipsed by the Americans and to cope with deficient critical frameworks dealing with such films back home. Some filmmakers she wrote about were Kurt Kren, Dore O, Werner Nekes, Heinz Emigholz, Valie Export, and Otto Muehl. (Return to reason (1975)[5]

- Interfacing with the art world: Birgit Hein was quick to grasp that the art world sometimes provided a better context for experimental film than traditional cinemas. In her curatorial work, she presented significant film exhibitions in art venues. Late 60s and the early 70s were also the formative years for artists’ film and video, growing out of the Happenings movement, Fluxus and Land Art in the US. Birgit Hein wrote about these films, demarcating works such as Gas station (1969) by Robert Morris and Frame (1969) by Richard Serra from other formally obvious ventures.In 1974, Birgit Hein would write the introductory texts for the revolutionary TV production at WDR, Künstlerfilme, that broadcasted films and videos by Richard Serra, Keith Sonnier and Bruce Nauman, commissioned by Wibke von Bonin, who was also instrumental in the realization of Fernsehgalerie by Gerry Schum in 1969-70.

Filmmaking

Birgit and Wilhelm Hein during the 70s often re-edited and re-used material from their previous films leading to multiple versions of certain films. This probably was in keeping with their firm belief that works of art should have an open and evolving form rather than the conventional closed form that suits historical canonization. Thus, some uncertainty hovers over the final versions of their films in this period.

Here I will take up the discussion of two films made by the Heins in the mid-1970s, namely Strukturelle Studien (1974, 23’) and Materialfilme (1976, 35’) to reflect on some of their relevant concerns at the time. Both films admittedly have multiple versions with varying lengths and presentation modes. The duration mentioned above are the versions I could access. Discussing Strukturelle Studien in 1976, Birgit Hein said,

“Strukturelle Studien is an open construction. It can be continued or changed without any danger of losing its essence” [6].

STRUKTURELLE STUDIEN (1974) © Birgit and Wilhelm Hein

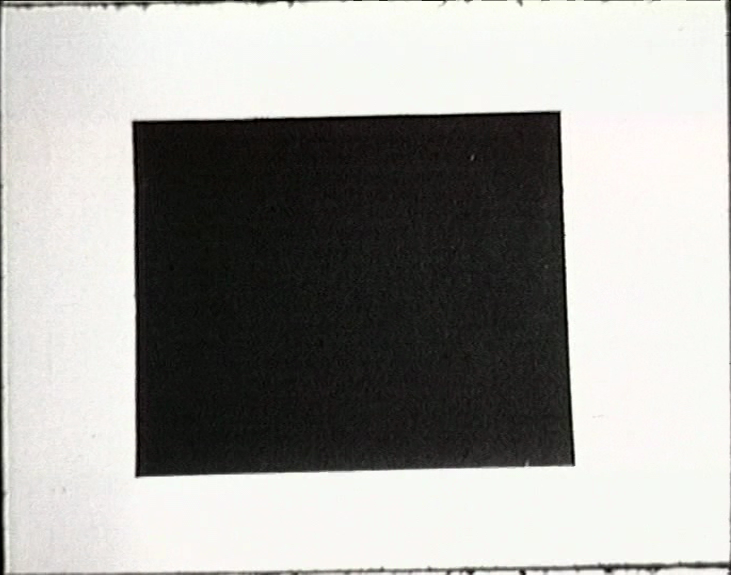

Strukturelle Studien sidesteps the expressionist character of many of the material films by the Heins and aims to illustrate and enlist different forms of movement and associated optical effects mimicking the manner of a scientific demonstration. This includes naturalistic movement, optical sensation of motion by the act of recording and projection/flicker, afterimage, phi-phenomenon, light movement (and its impact on spatial perception) and camera motion (variations in focal length). The film opens with the image of a black square on a white background, a probable allusion to Kazimir Malevich’s Black Square paintings which for the Heins “was the essential experience in the confrontation with contemporary art. … a zero point from which only new questions are possible”. For many of the contemporary artists in the 70s, including filmmakers, perception and illusion were key terms. A lot of the impetus in theory and practice was devoted to evince the illusionary devices of culturally dominant art/cinema. The film is episodic where each of the approximately 30 segments (excerpted from films finished by the Heins between 1969 and 1974) illustrates some form of movement. The film is quasi structural, the number of frames for each sequence was predetermined, however the sequentialization itself does not follow an evident (or withheld) logic, so the film does not progress in any set manner. It is a rational exercise of studying movement, depiction of which is among the key compositional skills of filmmaking. The focus on movement is of some other consequence. Andy Warhol aside, the Fluxus group (and associated filmmakers like Paul Sharits and George Landow) was the most impactful for the Heins, its founder George Maciunas named the group such (the Latin word Fluxus means ‘to flow’) to denote a constant state of non-stasis.

Materialfilme (followed by Weissfilm, 1977) is one of the emblematic material films by the Heins and is the culmination of nearly a decade of work dealing with materiality, representation, non-composition, and reproductional character of the film medium, which started with their iconic and most revered Rohfilm (1968). Materialfilme was initially conceived as a three-screen expanded cinema piece as Birgit Hein described it in Kunstmagazin (1977) [7]:

“Three-fold projection, with a scratch in each, the black leader, clear leader and the unexposed material. The three frames of the film are projected adjacent to one another and then over each other. At the same time the size of the images is varied and the projectors alternatively switched on and off. In this way a constantly changing image with different illusions of space and depth is brought about by the same basic material and projected onto the screen”.

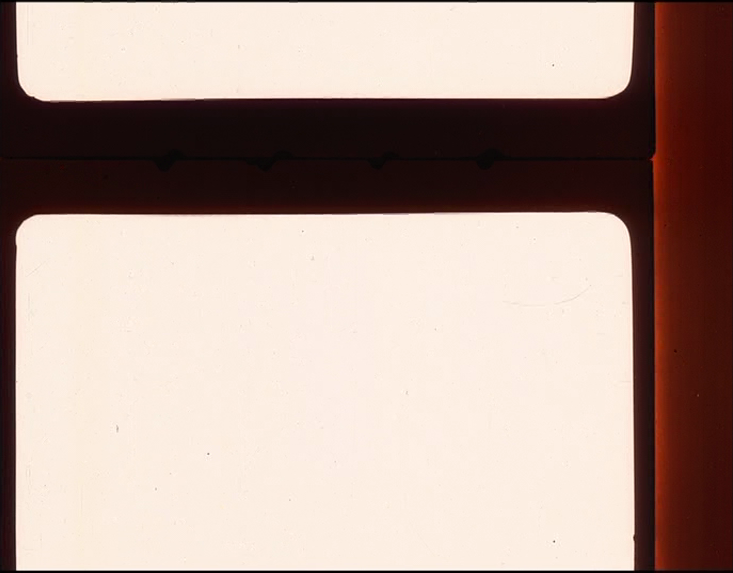

MATERIALFILME (1976) © Birgit and Wilhelm Hein

The film now exists in a different incarnation though, a single screen 35 min version on 35mm. This evolution from what Birgit Hein describes above (most likely on 16mm) to the existing version is hard to ascertain, though it surely would have involved re-photography and further addition of bits of film. The Heins combined new film with material that has been scratched by projection. This comprised film leaders (countdowns and China girls), photographed framelines, optical sound tracks, end-reel color paints and pure color frames. The physicality of the material, which is supposed to mute itself in favor of the pictorial content, becomes the subject of the film.

MATERIALFILME (1976) © Birgit and Wilhelm Hein

Materialfilme follows in the footsteps of Rohfilm, which was an articulation of how the image is a function of the optomechanical and photochemical processes of production and reproduction (shooting, developing, printing, projecting) of an image on screen. If Rohfilm is complementary to Alvin Lucier’s I am sitting in a room (1970) in the Sonic arts (for its concern with the material imprint of reproduction), Materialfilme more readily alludes to Milan Knizak’s Broken Music (1979) that relies on anarchic fragmentation and reassembly of the source material.

MATERIALFILME (1976) © Birgit and Wilhelm Hein

Curating

Birgit and Wilhelm Hein (along with 11 others – filmmakers and journalists) founded XSCREEN, a platform for screening independent films in Cologne, in 1968. They were inspired by the meeting of the European filmmakers at the Knokke Film Festival the same year. In Hamburg Das Andere Kino was already in existence thanks to Werner Nekes and Dore O among others, as were Freunde der Deutschen Kinemathek and Kino Arsenal in Berlin, a few similar initiatives from the time. Initially, XSCREEN showed films by the Austrian Film Co-op, Italian underground and Andy Warhol. Alongside such films, all the splinter groups from KPD, or the German Communist party in West Germany, showed their films – newsreels and political documentaries. The films from the New American cinema were extensively programmed, as were the films by Otto Muehl, which invited an intervention and confiscation of film reels by the police. The curatorial intent at this point was to identify and showcase films that would escape circulation through traditional channels. The programs tended to be monographic in nature or linked to a geographic area. The Heins, in keeping with their filmmaking, avoided anything beyond that – no dynamic cross curation based on formal or thematic threads (none of that curator as artist stuff), only the works had to meet a certain standard. XSCREEN was the torch bearer for later micro-cinema and underground initiatives, some of its members went on to become commissioning editors for television channels like WDR and ZDF.

Advertising for XSCREEN © Birgit and Wilhelm Hein

The other important curatorial arbitration by the Heins in the 1970s was in placing experimental film within the art exhibition context. Birgit Hein had written about the uneasy status of experimental film inside the cinema infrastructure (including non-commercial setups of arthouse and community cinemas). They had to contend with the challenges of exhibiting film in the art context with fixed starting and finishing time, possible sitting arrangements, and limited adaptability of film projection in comparison to video art. The two most consequential of such events were Kunst bleibt Kunst, Projekt ’74 at the Kunsthalle in Cologne and Film als Film at Documenta 6 in Kassel (1977). At Cologne the focus was on contemporary structural film while in Documenta, which Birgit Hein co-curated with Wulf Herzogenrath, the objective was to trace a long tradition of film’s existence within or in proximity to other visual arts (mainly painting and sculpture) from 1910s to the present day via display of art objects, light shows and expanded cinema performances alongside single-channel projections.

By the end of the 1970s, artists were beginning to get frustrated by the constraints imposed on them by museum spaces. The Heins, taking a cue from that, turned to performances dealing with marital and social problems in venues such as small cabarets and bars. They did not make structural or material films after 1977. They would only return to the cinema with Love Stinks (1982), an intensely personal film made during the couple’s year-long residency in New York. Birgit and Wilhelm Hein would eventually separate later in the 1980s. Birgit Hein would continue to make films on her own, occasionally curate film programs and teach at the HBK Braunschweig until 2007. She remains an unparalleled persona who donned the triple role of writer, filmmaker and curator with radical effectiveness.

Thanks to Marc Siegel for his inputs during the writing of this article.

[1] https://www.birgithein.de/

[2] Birgit Hein, Film im Underground (Frankfurt/M. , Berlin , Wien : Ullstein, (1 Jan. 1971))

[3] Birgit Hein, “Der Strukturelle Film” in Birgit Hein, Wulf Herzogenrath: Film als Film. 1910 bis heute, Stuttgart 1979, S. 180-188

[4] Birgit Hein, “Avantgarde und Politik” in: Frauen machen Kunst. Ausstellungskatalog. Bonn 1976/77

[5] Birgit Hein, “Return to reason; On experimental film in West Germany and Austria” in: Studio International, Vol. 190, Nr. 978, Nov/Dez 1975

[6] Birgit Hein, “On Structural Studies”, in Structural Film Anthology, ed. Peter Gidal, London: British Film Institute, 1976, pp 114-119

[7] Birgit Hein, “Expanded Cinema.” in: Kunstmagazin Nr. 4, 1977