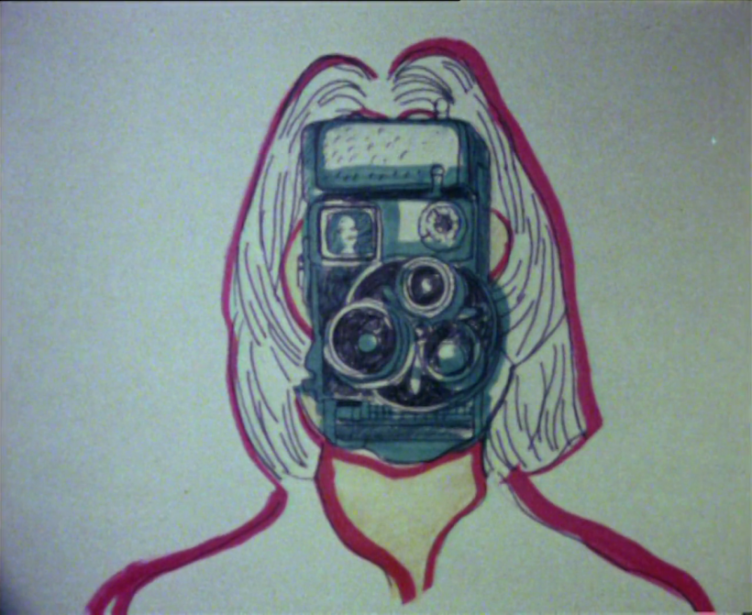

SELFPORTRAIT (1971) © Maria Lassnig Stiftung

For many visual artists who dabbled in the medium of film, critical appreciation of their filmic output remains secondary or correlative at best to the more vaunted harvest in the other arts, usually painting. We are of course thinking here about the inconspicuous category of Artist films that sits uneasily, cross legged, across the table from its cousin, Experimental film, engaging in scant and awkward social exchange. Films by artists often, but not without exception, gather attention by piggybacking on the reputation of the artist in the art world. They tend to draw the spotlight as the famed artist’s short-lived affair with experiments in a different media. The reception of Maria Lassnig’s films is not too dissimilar. The fact that she made animation films didn’t help with their reach since even within the marginalized terrain of artist films, animation remains a fringe subcategory. Maria Lassnig, the painter, is one of Austria’s most important artists, whose career, spanning over six decades, remains singular in many ways, marked by a body-aware self-representation in relation to space, objects, and animals that subsumes and eventually surpasses movements such as art informel, tachisme, and surrealism. Visual artist Amy Sillman describes Lassnig’s work as a study of

“how a body thinks and feels, the lived body as a compression machine of the imaginary, the symbolic, and the real”.

Lassnig’s paintings have been the subject of major group and solo exhibitions since the 1970s. In contrast her films, all of which except one were initiated during her time in New York in the 1970s, had an extended period of near total eclipse in terms of public exhibition since they were screened in close proximity in 1979 at the International Forum for New Cinema in Berlin and at the Austrian Filmmuseum afterwards. The revival of interest in her films is recent, most notably, the Petzel Gallery in New York devoting an exhibition to her finished films in 2011. This year Lassnig’s films returned to Berlin, as part of a special Berlinale Forum program, in conjunction with Anja Salomonowitz’s unorthodox biopic of her, MIT EINEM TIGER SCHLAFEN, featuring in Forum selection.

Lassnig attributed a great deal of importance to feelings and moods aside from the themes in her daily act of painting. The tactility and the possibility to transmit internal sensations from the heart to the canvas was a key allure of the medium for her. The camera though was an altogether different matter. Lassnig wasn’t interested in using the camera as a paint brush, she was conscious of the camera’s intervening power and understood that feelings and expressions here can only be translated and not merely transmitted. Indifferent to photography, it was the temporal possibilities of the moving image that encouraged Lassnig to embark on animation, a way to vivify still paintings.

Maria Lassnig was born in Carinthia, Austria in 1919 and studied at the Academy of Fine Arts in Vienna in the 1940s. She spent most of the 1960s in Paris and in 1968, she moved to New York. It is here that her painting would attain a new direction while she took up filmmaking as a serious vocation up until 1980 before returning to Vienna having received a professorship at the University of Applied Arts.

SHAPES (1972) © Maria Lassnig Stiftung

In her New York period, Lassnig attended a cartoon course at the School of Visual arts in 1971 and was a regular at the Millenium Film Workshop and the MERC (Media Equipment Resource Center). There she would acquaint herself with the basics of animation and meet other artists and filmmakers like Silvianna Goldsmith with whom she fostered a lasting camaraderie, first leading to showing films together at the Women Choose Women exhibition hosted by the New York Cultural Center in 1973, and in 1974, co-founding the collective Women/Artist/Filmmakers Inc. along with others such as Carolee Schneemann. During this period Lassnig devoted herself to animation filmmaking. She gravitated on themes of feminism, dance, history of the arts, self-portraiture, and non-anthropocentric metamorphosis between bodies and the inanimate world. Her characteristic jocular style was simple, effortlessly mixing seriousness and satire, live action and animation, text and image. Once she wrote in her notebook,

“My films are an antidote against the complexity of my paintings. My wish to be understandable and simple can be fulfilled through the added language in film. So, my texts are as important as the pictorial part of the film”.

Lassnig had an ad-hoc animation desk in her studio at West Broadway in Soho consisting of a light bulb, two plastic books on tinfoil, and a sheet of frosted glass with adhesive tape markings. She filmed using a 16mm Bolex camera. While she completed and signed off on only nine films in nearly a decade, she left behind twenty-five other films in different stages of production – unedited, partially edited, or simply unreleased– that she put away in a trunk and forbade anyone to access until her death. For many of these films, Lassnig left behind detailed plans in her notebooks and once she passed away in 2014, they became accessible thanks to the completion, conservation, and restoration undertaken by two of Lassnig’s former students– Mara Mattuschka and Hans Werner Poschauko. By taking full stock of her creative engagement with film, it becomes apparent that aside from animation, which was a dominant category, Lassnig experimented productively with pure live action narratives and film diaries. Working outside the experimental film trends in the East Coast– first person cinema or Structural film– the different strands within New American Cinema, Lassnig found a film language that embraced bold expressivity and instinctual improvisation, and while self-representation was a recurring motif in her films as in her paintings, they have none of the romantic excesses that mark the films of Stan Brakhage for example.

In one of Lassnig’s better known films, SELFPORTRAIT (1971, 4.5’), we confront the artist’s drawn face undergoing a series of distortions before flattening out as a canvas that hosts the figuration of her fears– of becoming what is pictorially depicted– a Woodhead, a camera, or a respiration aiding machine. In her Austrian accented English on the soundtrack aided by a musical accompaniment, Lassnig decompresses streams of thoughts, about being a woman, an Austrian in the US, communication gaps, death of her mother, the debilitation of labels, and yet the affirmation of her love for everything around. A flickering segment follows which Lassnig gradually stabilizes into frames of still drawings separated by black leader while voicing her desire to remain aware, to be in touch with her feelings, pointing to the layers that lie beyond the veil of the face. Lassnig is never shy of exacerbating the plasticity and malleability that the medium lays at one’s disposal. This is typical of Lassnig where latent biographical vignettes are satirized and humorized by mixing photographs, live action, voice, music, text, varying temporal scales, fragmentation of space, superimposition, and freeze frames. The films are evasive of a predetermined structure as they are of a singular theme gradually progressing and culminating in a humorous punchline, instead disparate motifs bleed into each other and thematic concerns echo across several films. In an essay from 1973 (Animation as a Form of Art) she identified Stan VanderBeek as working similarly with fragments of ideas rather than a story with a beginning and an end. Around the time she made SELFPORTRAIT, Lassnig embarked on elaborate conceptualization of similar projects which were eventually left unfinished– STONE LIFTING – A SELF PORTRAIT IN PROGRESS (1971-75, 7’) and KOPF (Mid 1970s, 1’). Though filmmaking remained on the back burner once Lassnig returned to Austria, she would make one last film, a musical biopic, which by her usual standards is less fragmentary. Here, clad vivaciously in changing costumes, Lassnig– in the foreground to her animated drawings– in a voice that walks the tightrope between ariose and recital, recounts wisps from her life as in SELFPORTRAIT – the domiciliary turmoil in her formative years, the social coercion for a domestic life, her struggles as an artist in a male dominated world, her time in Paris and New York, her involvement with art pedagogy on return, and her avocations in old age. MARIA LASSNIG KANTATE (1993, 7’) was produced by her colleague at the University, Hubert Sielecki and is based on a poem that Lassnig had started writing in New York.

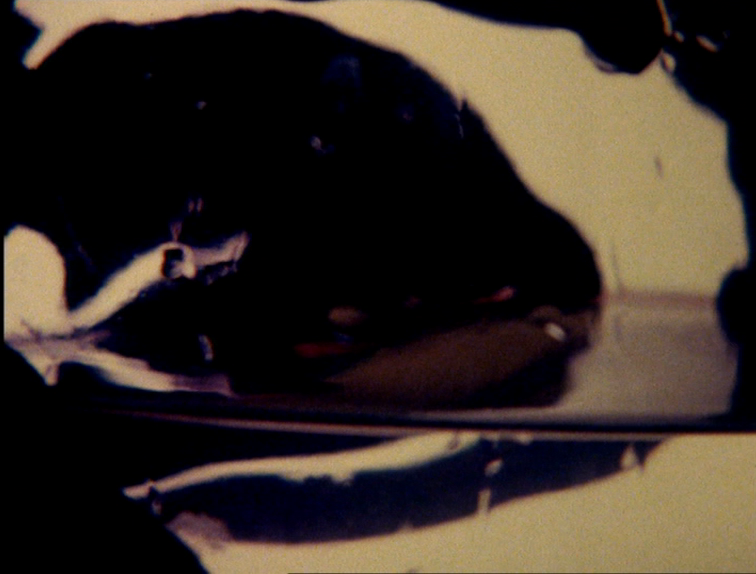

IRIS (1971) © Maria Lassnig Stiftung

But Lassnig was not entirely confined to self-portraiture and self-analysis. New York did provide solitude for her as an artist, but also opened up a world of organizing and collectivizing. A sense of isolation that permeates the viewer looking at the self-portraits is counteracted by considering a series of films from the same period titled SOUL SISTERS – IRIS (1971, 10’), HILDE (1972-76, 5’), ALICE (1974/79, 5’), and BÄRBL (1974/79, 5’). Sisterhood and feminist solidarity were in the air and members of Women/Artist/Filmmakers Inc. were actively involved in challenging male dominance in art institutions, codes of representation, and cultural censorship of the female body. SOUL SISTERS in many ways is an occasionally critical but largely tender and soulful testament to those times where Lassnig portrays friends she made in her social circles. She completed Iris during this period and left rough cuts with instructions about editing and musical scores for the rest. The compositional choices widely vary between these films, IRIS and HILDE both shot indoors deploy dynamic framing of derobed body parts and extensive superimposition while Alice and Bärbl shot outdoors are more of documentary character. One or a combination of music and narration appear in these films. IRIS, Lassnig’s formally most accomplished film, challenges the representation of the nude (she explicitly evokes Gustave Courbet’s L’ORIGINE DU MONDE), the ultimate muse of Western art, and tries to salvage sensuousness from the clutches of male voyeurism. Perspectival unity is abandoned in favor of spatially autonomous body parts filmed from varying points of view and sewn together as brief shots. Superimposition and mirror reflection then initiate a playful shadow dance between representation and abstraction.

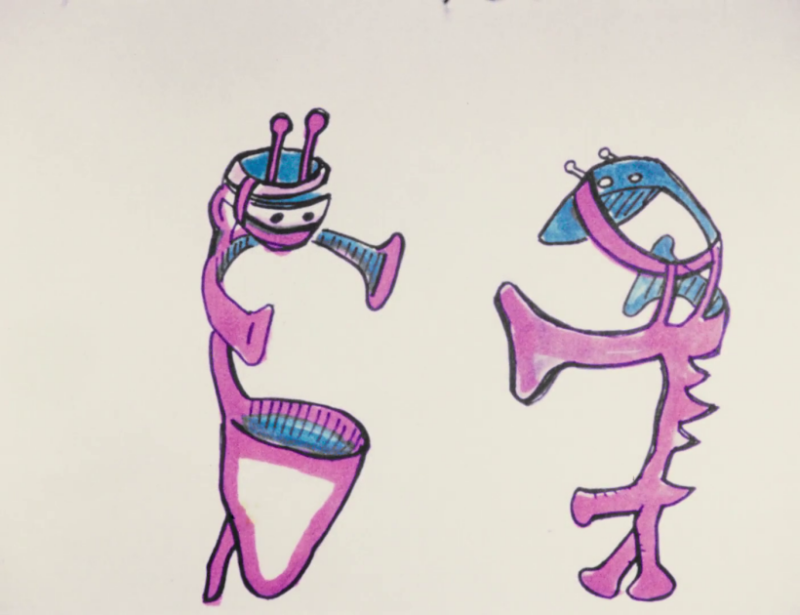

ART EDUCATION (1976) © Maria Lassnig Stiftung

Lassnig’s critique of the female figure as an image/subject (of the gaze) and the male– the purveyor of artistry from whom creativity flows – sharpens through subversive and humorous feminist readings of mocked up and animated canonical paintings in ART EDUCATION (1976, 8’). The male figure in Johannes Vermeer’s THE ART OF PAINTING (c. 1666-1668) voices his dissatisfaction and irritation at his female model since she is unable to strike the perfect pose, is emotionally demanding, and is older than ideal. Lassnig then flips this universe on its head, while the man, weighed down by the vagaries of age, poses naked with his saggy paunch, bald head, and flaccid organ, the muse turned artist now exclaims, “Honey, you’re a wonderful model!”. In further scenes we see the man in Filippo Lippi’s PORTRAIT OF A WOMAN WITH A MAN AT A CASEMENT (c. 1435-1440) narcissistically projecting his thoughts and desires onto the woman standing mute in front of him while Michaelangelo’s Adam (CREATION OF ADAM, c. 1508-1512) argues about his physical imperfections with the creator before challenging his divinity by pointing out that he is merely Michaelangelo’s creation, embodying viraginous traits. But perhaps the most formidable act of subversion by Lassnig is the insertion of her own animated characters within the macrocosm of male greatness, a couple sitting on a beach engaging in a dialogue that underscore their divergent views about marriage.

PALMISTRY (1973) © Maria Lassnig Stiftung

The absurd dilemmas of coupledom and skewed gender relations are Lassnig’s pet themes that reappear in films such as COUPLES (1972, 9’) and PALMISTRY (1974, 11’). In the latter, the possibility of intimacy between two heterosexual characters seems to hinge on a question that the man repeatedly asks his companion, “Is it the first time?”. In COUPLES, Lassnig points to the disharmony of expectations between a man and a woman in a relationship, be it sexual or how they each feel tied to it. In such films, Lassnig seems to deny the fulfillment of social expectations in both appearance and behavior of her characters. In not too dissimilar a manner, this denial is sustained with regard to human shapes and objects that constantly undergo physical transformations. These entities desert their socially determined roles by not conforming to spatial conventions or by acquiring shapes that seem mutant and not easily definable. Chairs are anthropomorphized with a pair of red lips and a phallus (CHAIRS (1971), 2’) and outlines of male bodies disintegrate into textures and patches via close ups and distortions (SHAPES (1972, 9’)). The choreographic and hypotonic nature of SHAPES summons the dance-sculptural film CIRCLES II (1972, 8’) by Doris Chase and points to another of Lassnig’s filmic preoccupations- dance. Lassnig counted Maya Deren among the influential figures in the history of experimental film and BAROQUES STATUES (1970-1974, 15’) attests to that along with two other unfinished projects – AUTUMN THOUGHTS (1975, 2’) and BLACK DANCER (1974, 1’). BAROQUES STATUES comprises visual and formal dualities – animation of still poses and live movement, a statue and a body, static and hand-held camera, single images and multi-exposures, slow and naturalistic motion (with occasional freeze frames), positive and negative imagery. Lassnig brings out the dynamism and eclecticism of Baroque dancing by relinquishing realistic depiction using the entire range of technical possibilities.

BAROQUE STATUES (1974) © Maria Lassnig Stiftung

Dynamism and eclecticism are perhaps also an appropriate description of Lassnig’s films. They refuse to be taken hostage by trends and movements; they aren’t just complementary to her paintings. They remain fiercely original and offer no cheap thrills while being humorous and playful. Gender discrimination in art history along with self-awareness are lasting themes and in the 1980s, she was the only one offering a practice-oriented film course in Vienna, in conjunction with an animation studio which she had opened. In the day and age of social media when self-affirmation and validation are highly sought after, Lassnig’s objective introspection in her paintings and films stand tall as a perfect antidote.