James Edmonds, Movement and Stillness, 2015, Super 8 Stummfilm, 11Min., Farbe

A fleeting view of a garden through a window. The sky a radiant blue, completely cloudless. A close-up of an insect, intently pursuing its purpose. In James Edmonds’ filmic universe, only rarely does a person traverse the unfolding events as a nameless, marginal figure. The British artist and filmmaker, who was born in 1983 and studied fine arts with a focus on painting at Brighton University, has lived and worked in Berlin for several years now. Commencing with canvas and paint, he became drawn to filmmaking during his studies. He brings together both – filmmaking and painting – in exhibition settings, utilising his painted canvases partly as projection surfaces or applying pictorial gestures to the film frames to engage in the events occurring there.

Already in his childhood, Edmonds took his first tentative approaches to the film medium, during which his fascination developed especially for the actual materiality of that which is film – the film strips themselves, on which not only do lasting memories permit themselves to be captured in the form of individual photographs as unique snapshots, but also arranged in sequences as motion-picture scenes. To which, thanks to the chemical process, an echo lingers that outlasts time. This understanding of film that commences with the material, and with it the subject of remembrance and its transience, has been omnipresent in Edmonds’ artistic practice to the present day.

Later on during his time at university, James Edmonds became familiar with and cherished the world of European arthouse cinema, and began to explore and research in detail the origins of popular cinema-release movies. He was interested especially in film-theory approaches that drew a connection between the early era of cinema and the social openings that occurred in Europe at the start of the 20th century. One could mention here the figure of the flâneur, for instance, or the emergence of the shopping and leisure culture, which established itself increasingly as a mass-culture phenomenon at this time. For it was exactly this leisure culture that permitted the rapid success of European film and, within this context, cast the figure of the flâneur onto the silver screen as a representative of this new attitude to and zest for life. James Edmonds also observes current social phenomena in his films, yet without adopting a value-oriented approach.

Parallel to his studies of early narrative film, over the course of his further artistic education and training, James Edmonds focused his attention increasingly on the work of various experimental filmmakers and their liberated treatment of the filmic conventions of space and time. Jonas Mekas – with whom Edmonds associates a sense of cinematic freedom and filming for the sake of the medium – has acted quite evidently as his model, with his influence also always resonating in James Edmonds’ works. In this respect, the sequences are short, from the length of a blinking eye to a single frame, and are loosely strung together, returning to the same locations at times, or bounding through differing contexts removed from space and time.

Thus they are also reminiscent of the experimental films by Stan Brakhage, a further artistic role model for him. Moreover, in addition to Brakhage’s works, parallels may be drawn to Werner Nekes, Jeff Keen or Dore O., as well as to filmmakers such as Helga Fanderl, Robert Beavers and Ute Aurand, whom James Edmonds knew personally, who likewise have developed their filmic works commencing with the analogue film medium.

One significant aspect that also arose from this initial era of intense engagement with experimental film was the interplay of the music and the image – the score – which has continued to shape and characterise James Edmonds’ work to the present day. A fellow student at university showed him one of her Super 8 films, whose frames she had synchronised to music she had composed, and this swept James Edmonds away into a world in which time apparently played no role. The images and sound in the form of spontaneous improvisations would be screened in the local cinema, Brighton’s “Cinematheque”, where local filmmakers presented their latest works and musicians provided improvised accompaniments to them.

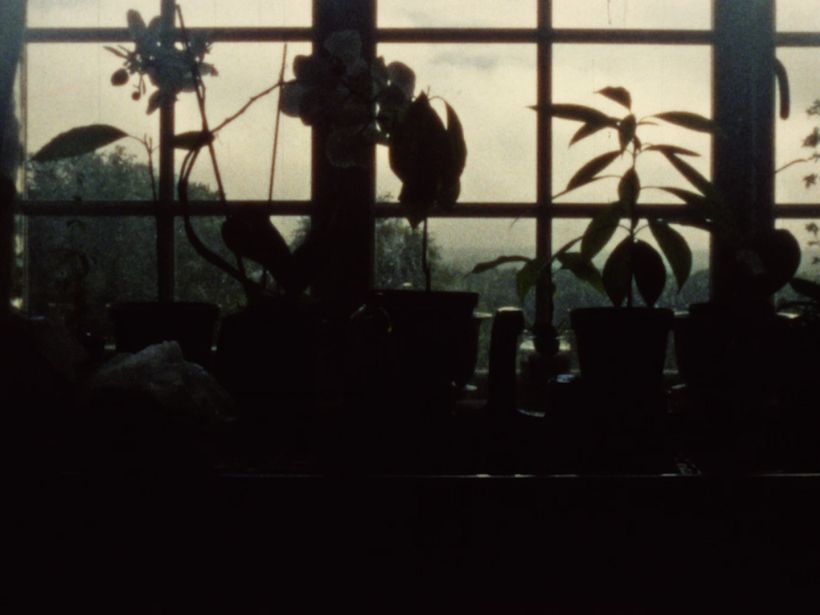

James Edmonds uses both 16mm and Super 8 to captures his impressions of the world, which are arranged together loosely as sequences of momentarily captured snapshots. Doing so, he utilises the narrow-gauge film, the granularity of the material and the inertia of the camera for his own creative purposes. In this way, extreme plays between light and dark arise, for instance, over which the properties of the material are imposed like an additional filter. The inertia of the adjusting light as the camera pans, the slowness of the zoom feature – these are things that interest him as a filmmaker and tantalise him when handling the camera, and with which he plays in his experimental short films so as to generate atmospheres. Doing so, James Edmonds, who sometimes uses out-of-date film stock, lets chance prevail when unintended colour shifts or defects in the material results, or pre-exposures are superimposed over the view he is trying to capture.

While the editing occurred almost exclusively in the camera itself in his earlier works, he has post-produced his more recent works on the editing table. Here too, he lets himself be inspired and guided by the material, rolling the dice anew, so-to-speak, painting over scenes and subsequently adding artificial black pauses doing so, or letting the scenes end in hand-drawn amorphous forms full of colour that thrust themselves at times over the frames shot previously.

In his 16mm films, James Edmonds thus gives expression to the possibilities of analogue editing, with space an overarching theme in this regard as the near and the far converge. For him, the film emerges from the physical handling of the film strips, from dealing with the material, which follows certain rules and yet still permits experiments. Film as film is what interests him, as James Edmonds indicated at a talk during the screening of a selection of his films in the Kunsthalle Mainz art venue. He characterises the genesis between analogue and digital film as being fundamentally different and not comparable in terms of the result. James Edmonds regards analogue filmmaking as an art form, as an expression of a complex aesthetic discourse that requires and demands exploration.

He also learned his craft, his handling of the material, under Robert Beavers, whom he assisted with the restoration of Gregory Markopoulos’ film cycle “Eniaios”. This trained handling of the material ultimately accorded him a new understanding of the “completed film” as something temporal, but also physically tangible in space, that can be processed by hand. While his earlier filmic pieces seem raw and unfinished, with rough edits for instance, his work has developed to involve the practiced application of various possibilities for grasping the film reel as a medium, with the design and structure of the finished film in and about this.

James Edmonds, A Return, 2018, 16mm Film, 6 Min., Farbe, Ton

This is apparent especially in his latest cinematic work “A Return”, which received a special mention in the German Competition section at the International Short Film Festival Oberhausen. Yet again, atmospheric images are arranged in sequence here, with special attention accorded to the lighting. This moves between the two extremes and explores limits. In this way, we feel reminded of the rhythm of life by day and by night – awake and asleep, living and dead. With each short scene incoherently following the next one here and condensing to create an atmosphere that permits complete submergence in this rhythm. Likewise, the filming process itself is expressed in a mirror image that shows the filmmaker at work with the camera in his hand, through which he becomes both the observer and the observed at one and the same time. James Edmonds has overlaid this flood of images with a self-composed soundtrack that is as abstract as it is atmospheric, and which underscores his truly unique pictorial language with its soft tones.

James Edmonds’ films do not follow or observe some screenplay, but rather moods, or even patterns, that he rediscovers in differing locations and which can be understood as visual echoes that he reveals during his exact observations of the world. At times, these patterns are effected by a specific lighting atmosphere, like in the short film “Movement and Stillness” from 2015, as indeed by movement, architectures, a certain rhythm or form, like in “Seasons/Patterns” from 2018/19, before then reoccurring as specific moods, such as loneliness, stillness and movement, city and country life, which James Edmonds traces and confronts as contrasting pairs. However, this idea of film never imposes on the reality of the film itself, which the filmmaker understands to be a separate, independent object. And doing so, the medium itself always remains present in the foreground, yet without reducing itself completely to this and obscuring its own visual language, which is capable of creating unique atmospheres.

Filmography:

A Return, 2018

Overland, 2016

Sternwarten der Welt / Sun Documents, 2010-11 / in progress

Inside/Outside, 2008/2015

Fleeting Landscape, 2007/2016

we will live in the blue image forever, 2007 / in progress

Fragmente/Structures, 2006-07/2009

After Hours, 2005

1 Trackback