Driving around where the Crescents Used to Be. A Script © Marian Mayland

“Please Stop Breaking the Windows. Still Occupied,” a text panel that casually appears in Marian Mayland’s first single-channel video work, already pointing in the direction of her later films. Driving around where the Crescents Used to Be. A Script (2015) reconstructs in a collage of collected material the former location of an architectural utopia: the equally imposing and infamous Crescents in Manchester’s Hulme district, brutalist social buildings that in the 1970s replaced old, dilapidated architecture and were themselves considered uninhabitable due to construction defects only 20 years later. As it moves through a collage of archival and amateur footage, fragments from TV series and cartoons, computer game footage, rave recordings, and found quotes, the video captures the browsing movement through which Marian Mayland’s research process may have unfolded. A reading that follows the wandering gaze of the Internet flaneur, along the material, from a varying distance and through different layers of fictionalisation, from which, provisionally and unfinished, a script emerges. It is part of an extended artistic practice that already developed during her art studies in Essen and Basel between drawing and text, space, and the moving image.

The script as writing paves a path through an urban landscape that is simultaneously abandoned and present, destroyed, and deeply embedded in local memory, mediating between interior and exterior spaces. She taps into the psychogeography of a place where, from the beginning, utopian notions of a new form of coexistence overlapped with the speculation of more efficient social control. The text panel quoted at the beginning hints at the fragile sociality that emerges from this contradiction: the aggression against an inside that doubles the trauma of a gradual uprooting, but also the attempt to continue living in the edifice of a utopian construction that no longer can withstand.

Eine Kneipe auf Malle © Marian Mayland

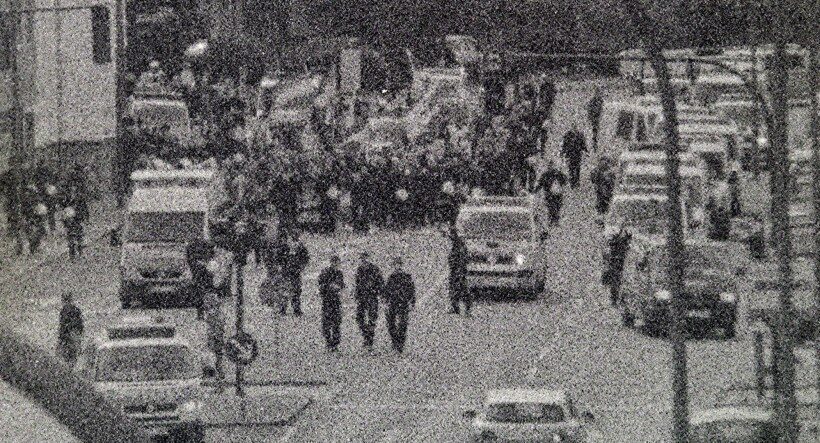

Mayland’s cinematic works interpret landscapes as political, medial, and psychological formations in which history and stories become visible without a directly demonstrative or narrative gesture to present them. This is replaced by the peripheral gaze and indirect or meandering speech, the aimless wandering, the disturbancer at the edges of the image, the noise of translation. The material basis of Eine Kneipe auf Malle (2017) is footage of an NPD demonstration in Essen, which Mayland shot on expired Kodak Super 8 films of different generations. Based on the coincidence of two “obsolete phenomena,” the voiceover reflects on the afterlife of the extreme right in new, political pseudo-alternatives, on the parallelism of political and media noise, of Novalis and Mallorca, of narration and misrecognition. In its entanglement of image and text, the film develops a suggestive pull that can itself serve as evidence for the author’s marginal remark that the essay film is probably particularly suited for conspiracy theories. Not entirely without irony, the author herself enters the picture at the beginning and end of Eine Kneipe auf Malle: as the one who supposedly orchestrates the projection – the technologies of presentation and seduction.

Untitled (a refusal of leave to land) © Marian Mayland

She also plays a role in the subsequent films – as a voice, a researcher, and a questioner who is involved in and has a connection to the places and stories her works unfold around. Even though Untitled (a refusal of leave to land) (2017), for example, extends between quotations from Joseph Wulf and Walter Benjamin, while the time period the film outlines encompasses prehistoric Deep Time to the present, she continues to narrate her own story through these historical timelines and ruptures. Not a narcissistic self, but one that is constituted at the intersections and through the overlapping of different narratives.

In Untitled, an ammonite that the artist found as a child in a railroad bed not far from her home serves as the trigger for research into the visible and invisible connections between this railroad line, a prisoner-of-war camp in her hometown of Bocholt, and the history of the Krupp family, its involvement in the Nazi extermination apparatus, and the political structures of the Federal Republic.

In static shots, the film takes us from the outskirts of Bocholt and Essen to the Krupp corporate headquarters, visually located between local recreation area and stereotypical panorama of structural change, which only through the voiceover are made recognisable as parts of a different geography. Like that asteroid whose impact 66 million years ago left a huge crater that today can only be measured as a deviation in the earth’s gravity, the traces of inconceivable crimes have disappeared –removed, hidden, disfigured, or stolen in the name of a family history. The infrastructures of remembering invariably also serve to forget.

The film persistently directs its attention to the surfaces, to the everyday (in)visible, until it enters a completely different landscape at the end: a nameless landscape into which the anti-monument of Portbou[1] carves a path for the memory of the nameless. The permission to land, referred to in the title of the film, then also points to the impossibility of arriving and staying in either of these landscapes. Rather, they cling to the heels of those who move on, stick to them, like the memory of that Krupp settlement the artist moved out of years ago.

Michael Ironside and I © Marian Mayland

The question of how spaces and lives adhere to and communicate with each other runs like a thread through Mayland’s films. Michael Ironside and I (2021) and Lamarck (2022) move through a succession of real and fictional spaces that mediate between autobiography and social condition.

They relate to each other like sibling films. Originating from the same research and initially conceived as one film, they show clear thematic references, but formally take different paths. Michael Ironside and I is based on found footage from well-known science fiction films and series from the time of the artist’s youth. We see static shots of interiors – living rooms, dormitories, submarine control centres –from which their male occupants have been removed. These rooms speak. Like the period rooms of a museum, they use furnishings and technical devices, colours, and designs, patina, and special effects to convey the fictionalised norms and atmospheres of a social status quo – in this case the 1990s.

The voiceover talks about the lives of the performers outside of their films, the diffusion of genre and gender conventions into social conditions, and their consolidation into forms of normalised violence that continue to shape adolescent and adult self-conceptions up until the present.

Lamarck © Marian Mayland

The rooms are therefore not closed, however hermetic they may appear. They form passages and leave escape routes open – even if it is not always clear where they will lead. They also allow the artist to approach a highly personal subject via the detour of narratives that are not her own. Their echo still resonates in her subsequent film Lamarck. Here too, spaces function as emotional signatures in which all things, gestures, and pitches speak and mean something, refer to one another, are related to one another. Lamarck is a film about speaking – a reserved, indirect, de-escalating manner of speaking, in which proximity always resonates as a place of longing. More precisely, the Mayland family’s speaking about itself: about or rather around shared memories, traumatic experiences with mental illness and suicide, never-realised ideas of a different, better life.

The film opens with an off-screen comment by the father about the omnipresence of military pilots in West German airspace in the 1980s, locating everything else against the absurd threatening backdrop of the Cold War. This is followed by an improvised family constellation in front of an open-cast mine – parents, brothers, partner, and daughter of the filmmaker placed in a post-apocalyptic moonscape. This is exactly where the film returns to at the end. A second take in the same constellation, but please now as relaxed “as if it were the first time.” In between are conversations recorded over the course of three months in and around the parental home and with the siblings, commented on, countered, or ironically accentuated on the visual level by glimpses of furnishing details, photos, and objects of sentimental value. The irrevocable order of “plate cloth – cup cloth – knife cloth”; letters to “Dear Grandma,” whose oppressive presence is felt beyond her death; the plant nursery as a legacy and mortgage on future life; the sagging campaign advertising ball as the remnant of a politicisation. They blend into a gently questioning portrait of a family whose communication is relieved by Mayland’s montage. For no one has to say what the things have already told. Gestures and glances will close the last gaps. It discreetly participates in this search for a common ground on which the unspeakable becomes sayable (even if it is in the mode of immoderate understatement) and the Chinese whispers of inheritance can be heard.

The question of what is transmitted, retold, and reproduced, and what control we have over it, also plays a central role in Mayland’s most recent film Outside (2023). Her first scenic work revolves around the biography of a German artist who was received as an outsider artist, primarily with images in which she ostensibly processed her experiences as a Jewish survivor of several concentration camps. It was only after her death and on the occasion of a planned homage by her hometown of Recklinghausen that doubts were raised about her self-portrayal as a Holocaust survivor, which were substantiated after further research.

Interviews with companions – a curator, a gallery owner, a historian, and a relative – staged as monologues in stylised studio settings, bring together reflections on possible motivations, contexts, and consequences of this misidentification. The decision not to identify any of the persons and to reconstruct the biography of an artist as a “case” in a model-like manner clearly highlights that there is more at stake than the question of the historical truth of an individual story. It is also about the question of how art positions itself between autonomy, trauma, and memory: How is the distance between artist and work measured? (How) can art bear witness to a foreign trauma? Is Outsider Art also beyond the scope of responsibility? Is an act of artistic self-mythologisation to be evaluated differently than the form of fictionalisation that is part of every self-concept?

As if for orientation, the camera repeatedly casts glances outside, visually linking self-statements and accounts about the artist with the everyday landscape of her hometown and incorporating them into the studio situations. The alignment, however, does not provide any final insights, no reconciliatory narrative in which what is said and what is shown coincide, in which history confronts us undisguised. Rather, without relativising historical injustice, Outside multiplies the perspectives from which a self and its relationship to the world can be told. It opens up a shaky terrain on which different realities overlap in an uneasy way.

As with previous works, Outside takes an abrupt turn at the end. The flight into the cosmos in Michael Ironside and I, the trip to Portbou in Untitled, the drone that rises above the open-cast mine at the end of Lamarck are like stepping out of the film, a detachment of our gaze from what we have seen before towards something new. Outside also leaves the constructed interiors, moving outside and letting us gaze into the evening sky, with the flickering spectacle of a large funfair taking place in the distance. The centrifugal forces of a fiction culminate in images of an abstract, collective ecstasy. A liberation? Deceit or dizziness?

[1] The “Passages” memorial dedicated to Walter Benjamin at the place where he died, Portbou, realised by Dani Karavan.