BACKFLIP © Nikita Diakur

The avatar trembles, barely able to stay up on its legs, then it falls over, its arms flailing. “Attempting a backflip is not safe. You can break your neck, or land on your head, or land badly on your wrists. None of that is nice, so my avatar does the trick,” an emotionless voice explains. The voice is that of animation director, Nikita Diakur, distorted using voice cloning software. Yet its dry humour does manage to penetrate even through the manipulative coils of the software. “Backflip” is Nikita Diakur’s latest coup, a 12-minute animated film that was created, or co-created, using artificial intelligence – or, more correctly, machine learning. A film which so enthused the jury of the 2022 German Short Film Awards, that, on 17th November, it won the Best Animated Film up to 30 Minutes in Length – the highest, most important and best-endowed award for a short film in Germany. Moreover, on an international level, “Backflip” has already garnered several prizes, including the award for “Best Design” at the prestigious Ottawa International Animation Festival (OIAF). Ottawa was not the first festival to prove that the film was not merely an amazing technical feat, but also an incredibly entertaining favourite with the audience. As his animation colleague Jonatan Schwenk recounts, they completely freaked out as they cheered on the avatar.

“Setting yourself some silly aim and then doing everything you can to achieve it – now that’s something we can all identify with easily, I think,”

Diakur commented with a smile about this particular screening. The avatar does not become a perfect athlete in 12 minutes. Instead, it blithely knocks all of the objects around it onto the floor and becomes entangled in a set of shelves. Body humour, body comedy, slapstick.

FEST © Nikita Diakur

Slapstick is a notion that often comes to mind when you take a look at Nikita Diakur’s works to date, be that his much-praised film, “Ugly” (2017), which scooped up numerous festival prizes, including the New Talent Award at Fantoche, as well as the Nelvana Grand Prize for Independent Short in Ottawa. And then there is his film, “Fest” (2018), which won the Golden Zagreb Award and the Short Tiger Award: Over and again, the characters trip up and stumble over their own feet, career into creatures and objects, causing the whole animation to collapse. The slapstick element – or better said: the enormous fun that can be had with the characters’ endless collisions – is often so present here that the film’s inherent messages risk being obscured. As Diakur says, it usually also happens that the audience finds the film hilarious, and then when he tells them that this is in fact a horror film, people laugh even more. But why horror?

“Because artificial intelligence is a technology like nuclear energy that’s not really controllable as such and can have some pretty serious consequences. We’re playing with something that we don’t actually have a clue about,”

or even

“something that could potentially break your neck – just like the backflip can.”

Yet despite the horror analogy: Diakur’s style of animation, one he certainly intends should make people laugh, is not characterised by the apocalyptic and the cynical.

“The world is grim enough, and I want to create ways to escape from it too,”

says Diakur,

“by making people laugh.”

(An aside: Diakur’s entertainment qualities even become apparent at various events: While other animation directors are visibly uncomfortable standing up onstage, he is quite capable of transforming talks about his films into highly entertaining events à la TED Talks). “Backflip” also represents his method for combatting his own fears, he says. Instead of feebly indulging in a bleak vision of the future, Diakur has in fact himself assumed control of the fear, the machine learning, here, in which a computer is trained to recognise certain principles and implement these in the form of solutions and actions. It does this by being fed repeatedly with datasets. In the case of “Backflip”, these datasets consisted of clips that show people performing backflips. Diakur spent two-and-a-half years working on his film, because he needed time, and iterations, until the avatar slowly learned.

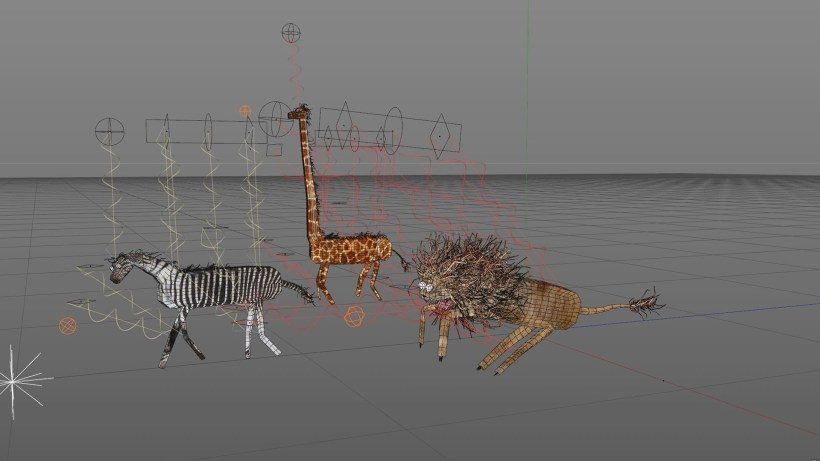

The element of slapstick in “Backflip”, created using machine learning, is an almost logical further development from his preoccupation with artificial intelligence. Prior to this, Nikita Diakur animated “Ugly” and “Fest” with Maxon’s Cinema 4D “Dynamics” feature, that is actually capable of simulating time-saving physical collisions, such as collapsing skyscrapers, for instance. He combined the feature with his characters’ 3D puppets: During the simulation process, the animator transferred the control to the computer, which interpreted the animator’s inputs with the help of the physics engine and created completely chaotic movement sequences in parts, because the feature was originally intended for entirely different “bulk” processes. The computer thus made its own decisions and in fact became a co-filmmaker. Moreover, this method presents an opportunity for Diakur to surprise himself – as the surprise element is largely absent from the animation process, compared to a feature-film set.

making of UGLY © Nikita Diakur

The results are manifold: Not only do the characters move in a trippy, manic way, they also involuntarily cause destruction. For Nikita Diakur, simulating the process of destruction in a safe, virtual environment is highly attractive – with the simulation being a way for him to explore the actual falling-apart as a physical process, as a space of possibilities. Non-rendered sequences that he inserts at times as elements of surprise, like in “Ugly”, and consistently at other times, such as in “Fest”, complement Diakur’s creative process. They are a means “to document the simulation.” And he continues:

“A rendered image is dishonest somehow. Sure, filmmaking often means telling stories that are not authentic anyway. But because these worlds are created on a computer, I think it’s better to put it out there, because their creation is also part of the story.”

For Nikita Diakur, it all comes down to “not faking too much”.

The filmmaker has come on a long and partly “analogue” route to his destruction of the perfect 3D world by means of artificial intelligence. Diakur, who was born in 1982 in Moscow and emigrated with his family to Germany in 1992, called pencils and paper his first creative tools: He drew from tenth grade onwards and took painting lessons. With the corresponding portfolio of work, he applied to take a foundation course in England that included the basics of drawing, as well as sculpture, theatre and design. Then he successfully completed a BA in Graphics Design and his Master of Animation Direction at the renowned Royal College of Art. Here, in addition to the eastern European animation artists, he also became interested in British luminaries and underdogs, such as Chris Shepherd, Phil Hunt and Jonathan Hodgson. However, the perfection that was the holy grail for the 3D animation scene at that time soon bored him; it was “too sterile”. Moreover, he missed the opportunity to surprise himself. This already shows in his graduation film from the London Royal College of Art, “Fly on the Window” (2010), which plays with constant changes in perspective: As soon as a living creature looks at another one, the narrative perspective “jumps” to that of the counterpart. This even accords the film – which was animated in 3D and also completely rendered in a “Pixar” style – its convincing rhythm, despite all of its “polish”.

The fact that Diakur has remained loyal to the animation medium, even after his graduation film, is linked quite specifically to the Animafest Zagreb, which selected his film for screening at its 2010 event. Attending the festival, he saw David O”Reilly’s “Please Say Something”, Priit Pärn’s “Divers in the Rain” and Johannes Nyholm’s “The Tale of Little Puppetboy” – all together in one screening – and he was so thrilled that he decided he wanted to continue making animation.

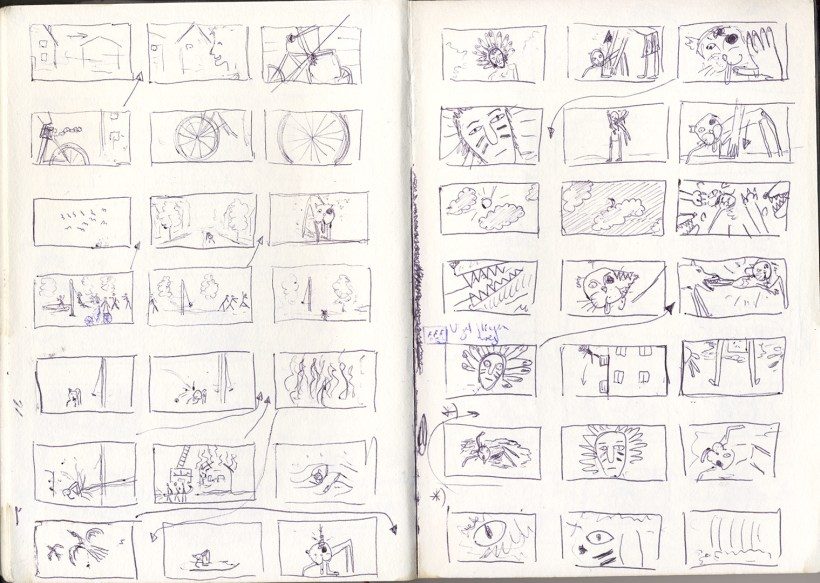

Storyboard UGLY © Nikita Diakur

A three-year block, caused by setting himself “disproportionately high standards”, was followed by “Ugly”, which Diakur completed in his free time and during his lunch breaks as a 3D designer with the German broadcaster ZDF. “Ugly” took him four-and-a-half-years, financed with a mini-budget of €11,000, acquired partly via Kickstarter. The film centres around an ugly one-eyed cat and its hellish daily struggle: It is either being attacked by dogs or catapulted through the air by a jet of water from firefighters. The only affection comes from the Red Indian Chief Redbear Easterman, whom the cat already encounters in a semi-hallucinatory state against a horribly dreary skyscraper backdrop, before it dies and reaches Paradise. A touch of “Last Exit Brooklyn”, but with a happier ending. Diakur’s inspirations here included the “Ugly the Cat” story then circulating on the internet, as well as viral kitsch. The film was widely celebrated in Europe but received criticism in Canada and the USA prompted by the current social discourses on representation and cultural appropriation there. A complicated discursive battleground, at least considering that “Ugly” is concerned with quite a bizarre made-up world; rather than it being some animated documentary with potential claims to authenticity. A grey area, says Nikita Diakur. Nonetheless he would not make it any differently today, because the character remains coherent and logical for him. And what is the lesson here? Namely that henceforth you can only make films about yourself? This is not something Diakur would like to accept – Nikita avatar or no Nikita avatar.

Only making films about himself would also be difficult from a practical, biographical viewpoint: He once said that he has “no roots” or at least feels that they are “scattered”. While he was born in Moscow, Russia’s war of aggression has made it impossible for him to now speak of it as home. Thanks to his wife, he is currently spending a lot of time in Mexico, a place where they call him the “alemán”, and he already feels a sense of connection with the country. Spending six months a year in Leipzig is also okay, but does that make him German? Who knows what it actually means to “put down your roots”, to “be tied down”.

Yet for that, the urban panorama in “Ugly” is definitely inspired by Russia, as indeed is the setting of “Fest”, Diakur’s second film after completing university. An amusing three-minute piece financed by the company Adult Swim. It depicts people in a skyscraper setting going crazy to gabber music, as well as a bungee jumper who plunges down from the skyscraper, taking down a food truck with him. The idea arose when watching random YouTube curiosities. Yet again, the protagonists are the same 3D puppets that he utilised in “Ugly”, and everything goes wonderfully wrong once again. Did he perhaps use an avatar in “Backflip” because he was running the risk of turning his puppets into parodies or caricatures? He shakes his head. The avatar was just the most consistent and logical thing to do, as he himself would have loved to do a backflip. And as for the characters’ partying and jumping in “Fest’ – you were never meant to laugh at them, for instance, but rather party and celebrate along with them.

Since Nikita Diakur’s films are now shown at so many festivals and regularly garner awards, he is able to collect FFA points (from the German film funding system). Thus, he is now always able to acquire sufficient financing for his next film projects, rather than having to survive doing gig jobs at ZDF. And until now this has also provided him with enough security to work on his upcoming projects. One of them is a film about the phenomenon of cumbia, a style of music cultivated in various Latin American cultures that is celebrated at fiestas rather than in dance schools. The first voice recordings have already been completed. Is he perhaps running the risk of being accused of cultural appropriation yet again? He shrugs. The people who are involved in the project in Mexico

“are just pleased that there’s going to be an animated film about cumbia.”

Nikita Diakur’s other project concerns interactive animation, a favourite pastime of his. Together with other animation directors, he is currently working on a kind of generative human intelligence that works in a manner similar to a gaming mechanism: You “transfer” the control within an ongoing process to the other director. And what is that going to look like?

“It’s all about an everlasting fall,”

or about someone who falls and simply never stops falling, explains Diakur.

For all the pleasure (of experimentation) he enjoys when co-authoring with other persons and computers: Of course, Nikita Diakur is aware that even this loss of control occurs within a controlled framework. Moreover, in order to tell the stories he wants to narrate, he does not just let the computer constantly whirl and spin of its own freewill; instead, he selects certain “chance occurrences” for the final film. Thus, even this freedom remains a compromise – yet one that, as he emphasises over and again, he would also like to continue approaching as honestly and transparently as possible. And we can certainly look forward to seeing whether this new human co-authorship also takes visual account of his (self) (de-)construction and invites the festivalgoers to snort with laughter and encouragement.