“I’d like to create images that fuel the illusions of memory,” says the artist Robert Seidel (1), who positions his work between film and projection art. This conflicting field of eroding forgetfulness and volatile reassurance is found between experiencing and recollection. He shapes and forms this flexible space of negotiation between the traces of the concrete and a constantly self-updating perception. To do so, he reams his way through sediment layers of the self-evident and reduces this down to its core, so that merely a drawn gesture remains.

Drawing from the series “glimmer”

He then returns from these depths, rearranging and layering on top of each other, transforming individual essences within a digital space, connecting them into an aesthetically impressive fabric that is capable of providing a fleeting hold to these threads of an ephemeral memory. Seidel abstracts, so as to sensually create an apparently familiar grace with painting, animation, light and space. Grace that traces the concrete at least in its possibilities when it is already not graspable. Doing so, Seidel seldom remains “short film-like” in a purest sense. Instead he shifts the coordinates of short film, such as the image framing, length and projection space. Then steps out of these in order to draw attention to them.

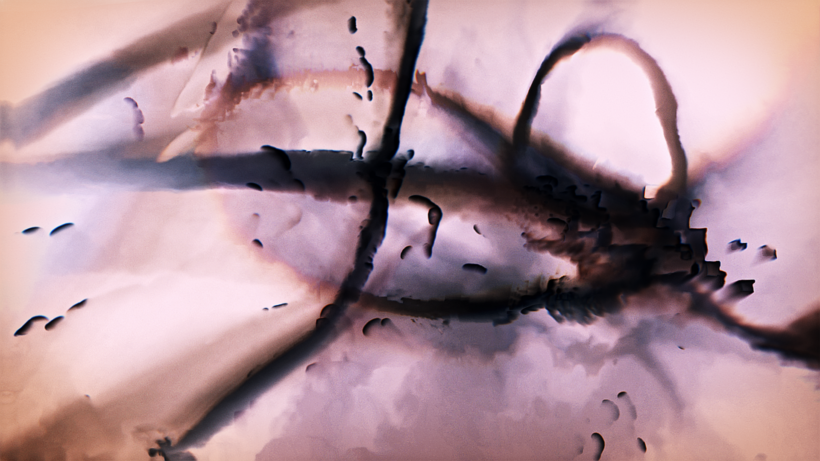

The audio-visual work E3, which emerged from a discovery phase, was created in 2002. In this video diary produced during a three-month stay abroad, he repeatedly subjected his own abstract gouache painting to extremely watery brushstrokes and digital transformations. The strokes and shapes slip and slide, shifting around and forming new structures. The changes are captured in single-frame shots, with the artistic result laid bare in the re-animation. No “final state”, no completed image exists, but rather the ceaseless state of the painting as such, the movement within the image. Seidel is fascinated by the temporal and the processual, which he is capable of making visible by means of film.

Already in 2004 at an early stage in his artistic career, Robert Seidel set an unequivocal milestone in the recent history of digital film animation with his work _grau. At the same time he made what is arguably his “most short film-like” work. Unlike in E3, time is not stacked up here, but stretched out. Seconds of an imaginary car crash become a digitally experienceable subjective eternity. Even the film’s length of 10:01 minutes is, in its binary readability, part of the conceptual framing. Seidel orchestrates the lack of orientation and the shreds of the experience from the existential situation of the car crash into a composition that brings together the fragments without them forgoing their autonomy.

sfumato, Supernova Festival, Denver, USA (2018)

The moment is disassembled, spread out like a flabellum against an empty background, as though on an autopsy table. 3D scans of body parts, MRI images of Seidel’s brain and organic elements referring to hair, teeth and bones remain vaguely recognisable. The sculptural slivers have strikingly natural geometries and visually create an organic fabric that never rests. Despite its abstraction, _grau appeals to our capacity for empathy in relation to bodily infirmities, proverbially getting under our skin while being half-stuck in a lab coat. This refreshingly complex and at the same time emotional approach in a non-representative 3D animation was rarely found in the short film scene in 2004, for which reason it caused a sensation at numerous international festivals.

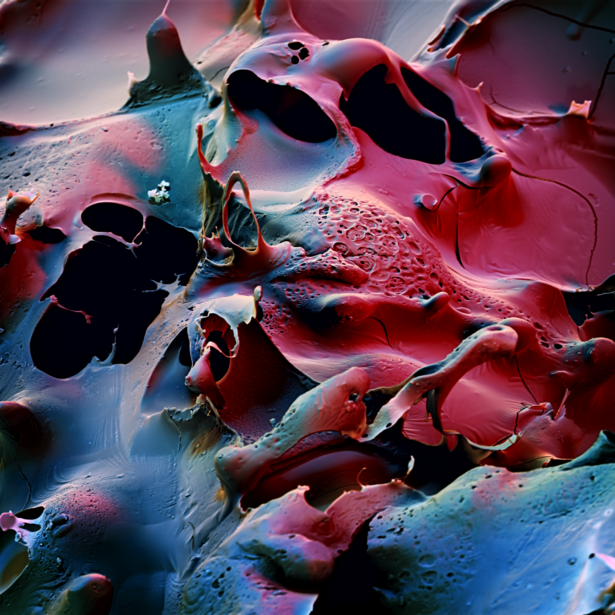

It is not by chance that art and science often converge in Robert Seidel’s oeuvre. Before deciding to take media design studies at Bauhaus University in Weimar (Germany), he was a biology student at Jena University for a while. The son of a physicist is still fascinated today by visualisations in the natural sciences – with the factual means of analysis there becoming an artistic tool for Seidel’s explorations. His aesthetic approach creatively abrases his exploratory interests, so-to-speak. Many of his works emulate observational studies from microbiology. The cycle of emergence and disintegration prevails in his dramaturgy, in which the edit as one of the central filmic tools almost never occurs. The pictorial masses stretch out cell-like via digital transformations and draw themselves together again.

“Pulsating” is arguably the paraphrase most frequently used for the breathing rhythm of the artist’s animated works. Protrusions and threads cautiously feel their way forwards like tentacles and encounter the borders of the neighbouring image cells. In _grau for instance, they form gentle fur-like surfaces with thousands of fibres, rolling as a whole through the image, leaving traces of light and colour behind. Seidel models artistic organic worlds into figures of time as they have amazed us since the early days of silent film, such as when for instance plants are shot in a single-frame process and then grow and bloom again rapidly in the shortest of time as though by magic when projected in the cinema. The continuous filmic-processual in combination with the aesthetic gracefulness of natural life processes elicits in Robert Seidel’s works a desire to watch that gladly embraces abstraction.

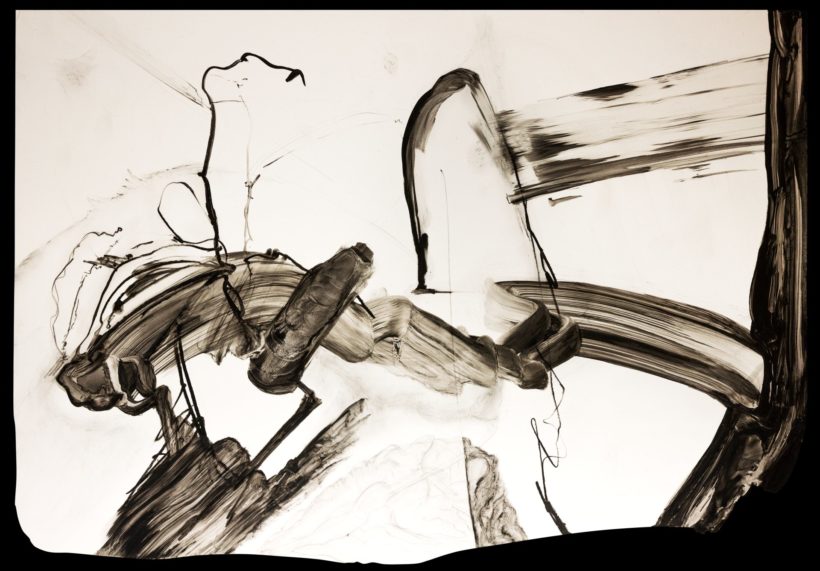

Preliminary study for “fulcrum”

This aesthetic provides many points of contact for differing areas: Visual arts, science, film, design and music. Despite the artistic focus of his work, as well as several commercial commissions he has undertaken, Seidel avoids one-sided appropriations. Yet likewise, he forges experiences: A major telecommunications company has utilised his uniquely original creative style without permission for their advertising; funders are repeatedly unable to allocate his works to their funding categories they themselves have named. Moreover, it happens that project-related support frequently does not provide the required space for his complex technical testing and experimentation. His vision here sees the need for a central laboratory for various artists working with projection art in order to be able to really break free from the structures currently handed-down. At least to the extent that in purely scientific facilities, access by externals artists to the expensive visualisation equipment there is still highly limited: On the one hand, due to a lack of interest in the artistic intensification this involves and, on the other hand, from the desire by the scientists there to protect their own ongoing research. Primarily for production-related reasons, he stepped back from cinema works after _grau to some extent, focusing instead on projections in galleries and public spaces. To some extent, because Robert Seidel regularly produces “documentations” to his expanded animation projects or releases parts of the projection footage as short films. And especially in the context of film festivals, these then make their way back into the cinemas. However, in Seidel’s experience, general audiences at the projection events beyond the cinemas deal with abstract animation in a far more open way than they do in a cinema context.

His first facade projection in 2008, which was called processes: living paintings, brought together science and animation anew. The front of the Phyletic Museum building in Jena became a screen for Seidel’s living paintings. With them taking over the building with some meandering, kraken-like gestures. The archetypes that appeared and their transformations formed references to the collection in the evolution history museum established by Ernst Haeckel in 1908, as well as to Haeckel’s artistic-creative depictions of his research findings. The visual elements were subordinated only to a limited extent to the architecture of the building’s facade. Regularly recurring architectural forms, such as windows for instance, and the entrance area were playfully incorporated. With choreographies of light radiating through the windows out of the building’s interior in symbiosis with paintings projected onto its outer skin. The light and video layers run in opposite directions. The resulting duet was played back as a loop, although there was no permanent repetition of the same content: The musical framing – a sound collage from Robag Wruhme – had overly long loops, and through this the sounds in phases constantly extended into the neighbouring images.

Unlike with his works for cinema, the artist’s projection works are also generally location-dependant, meaning that they are primarily created in an exchange process with the relevance, dynamics and situation of the specific local setting. The location for scrape (2011) was the extremely busy Seoul train station square, which is encased in countless advertising displays. On the outer surface of an office building, whose LED-fitted facade was one of the largest in the world at that time, luminous monochrome layers scrolled out of the darkness. At one of the most intensely commercialised locations of rush and haste, scrape absorbed the advertising lights from the darkness of the night and created a contemplative situation that was sufficient in and of itself, and which erased every economic value.

MUE, Palais des Beaux-Arts, Lille, France(2018)

In order to be able to react to the respective conditions and challenges of his projection locations, Seidel continuously adapts his working processes:

“The challenge with projections and installations is that you conceptualise ideas that work perhaps as filmic images, but don’t do so anymore as such in the projections. A part of the image is too dark, the movement is too slow or the contrast is not high enough. That’s why I keep my creative options open and first fashion my material into its final shape and structure on location.”

The subsequent realisation of the projects’ documentation in a short film format thus represents the artistic challenge of being able to effect closure to an open form.

Robert Seidel retains the processual aspects of the filmic in his works, yet for that he has continued to disengage himself further from cinema by intensifying his endeavours with projections in real space. In advection (2013), abstract light paintings were projected onto a water fountain. Fluid shapes like huge brushstrokes or crystals floated bodilessly over a fountain at the Lichtsicht Projection Biennale in Bad Rothenfelde, and seemed even more organic and spatial because the masses of water did not form a static screen and the light was constantly refracted in it.

As a radical contrast to this, the artist permitted static but non-flat surfaces to breathe in folds (2011). In Lindenau Museum in Altenburg, he clad plaster casts of ancient sculptured torsos in abstract, coloured folds of light. The moving light was cast distortingly around curves, nestling itself into dark folds and forming artificial shadows at unexpected places, before instantly moving on. The spatial dimensions of the statues became multiplied and reshaped. Which could be experienced without having to change the viewing position. The real torsos shimmered through the projection, continuously changing their character – held in the abeyance between vision and illusion.

In 2017, Robert Seidel undertook a similar reinterpretation of found objects but on a far larger scale for the Digital Graffiti Festival in Alys Beach, Florida. The tempest installation involved building facades, artificial fog, water fountains and parts of a park landscape, and it structured the space using differing painting and drawing techniques as well as a soundscape by his long term collaborator Nikolai von Sallwitz. The screen became voluminous and spread out framelessly upwards, sideways and down in the depths, depending on how much light there was and where it was being reflected from the wind-blown wafts of fog and nature. The fascinating beauty with which the surroundings were overlaid with vibrant colours and structures from differing painting and drawing styles proved unsettling due to its discontinuity. Seidel created tempest (reminiscent of Shakespeare’s “The Tempest”) in the knowledge of the dramatically changing weather conditions at this location. The illuminated trees seemed like the invocation by the magician Prospero come true when a storm brought unplanned additional movements and flashes of lightening into the installation during the projection.

In the trilogy: black mirror (2011), tearing shadows (2013) and grapheme (2013), the projection became a sculptural installation – as Seidel ruptured the screen to become a walk-in film. In order do so, complex organic paper and plastic shapes – sculptural reproductions of his drawing studies – were arranged in the space. The artist had collected the drawing studies in diary form over a longer period of time.

The transferring of the drawing studies into the three-dimensional reality of the exhibition space, the route to be taken through the fragile sculptures and the changing relations these had to each other as a result, the brief transformations of the sculptures caused by the moving painting projected onto them: The trilogy was comparable to a perpetual process of becoming and realisation. The sculptures appeared to act at one moment like fixed, graspable bodies in space, before behaving almost immaterially a moment later.

Likewise, abstract drawing studies provided the source material for vitreous. Created in 2012 as a large-format LED facade artwork and then finalised in 2015 in a short film version, Seidel fashioned virtual sculptures out of drawn two-dimensional elements to do so, which led their own lives, interacted with each other and warped themselves into complex meshworks. These hybrid entities did not hide their natural flatness, yet they did press into the depths of the image at the same time.

In one of his curatorial projects Robert Seidel took another route. While his curatorial works such as for the Austrian Film Museum, the Kunstsammlung Jena art collection, the Denver Film Society or the Künstlerhaus Bethanien art centre in Berlin availed of classic exhibition and screening formats, Crystallized Skins, a pavilion in “The Wrong – New Digital Art Biennale” (2015/2016), was devoted to virtual sculptures that were created by thirteen international artists. Their matter, consisting of polygons and the designing DNA, arose from digital animation. White, textureless and static, these sculptures referred to plaster cast collections of ancient sculptures steeped in history. However they did exist in a threshold zone of perception: It was possible to experience them three-dimensionally in the pavilion, or as they were originally conceived. Yet their actual habitat remained the two-dimensional film.

With Husby-klit bk., Robert Seidel returned to the cinema screen in 2017. However, the work is at home in many other contexts as well above and beyond this. In a dialogue with the music piece of the same name from the band Esmark (Nikolai von Sallwitz and Alsen Rau), Husby-klit bk. alternates between being a music clip and a visualisation of sounds through to being an experimental film and an installation – depending on the exhibition context. As is the case with many other works, Seidel used software he himself developed in order to immerse himself in the live performance character of Esmark’s working method especially, so as to instinctively and improvisationally combine his visual elements with the sound elements, such as in the Soundart 2018 event in the WDR Funkhaus TV broadcasting centre in Cologne. With the clip on the internet or the film in the cinema merely being one version, one interpretation of that situation in which it was created.

By contrast in the Weilheim Municipal Museum, Husby-klit bk. was exhibited scenographically. A museum room became a diorama, on which the ecstatic structures of the projected video images glided over regionally historic everyday objects and across the walls. For this, Seidel arranged individual exhibits separately to some extent. In this way, a small incense burner briefly grew to become a huge shadow tower that disappeared like a chimera a moment later in the diffuse, pulsating fog of the video light. The surfaces of the museum objects were newly appraised haptically through the visual perception. The static historical picture there, asserted by the space as being a museum setting, began to falter, proportions kept changing, and distortions arose flickeringly. The exaggerations resulting from the video projection created a new focus.

sputter, series of micro sculptures captured with electron microscopy (2015)

For Robert Seidel, such artistic shaping and creativity are the result of a long process of experience:

“Fifteen years ago, I would have visited the museum and looked for a piece of clear wall that would work for me as a screen for the projections. But the location was made to be changed. Nonetheless, I worked here solely with the timber framework that provided a far more enclosed framing than with the completely open tempest, for instance. But this approach proved to be excellent because many of the artefacts in the museum are frequently exhibited in frames and display cases. And the viewer often thinks that objects in such frames are a detail or a part of a whole – in the sense of a window onto something larger. However, if you don’t have such a frame, you have to create the illusion that something is large and all-embracing because the framing edges are lacking that would suggest it continues beyond them. But for that, you’d have to clarify some technical obstacles in turn that’d make a production cost intensive because of the more powerful projectors required, among others. And the artistic performance itself then quickly becomes a fraction of the calculation.”

The distorted video footage in Husby-klit bk, which was originally real, indicates in fleeting forms objects found on a woodland walk. Tree bark, ferns and scattered sunspots on grass shimmer through the overlaid images. The work’s basis consists of travel shots that Robert Seidel collected without a specific aim but because of their visual expression. The shots do subsequently detach themselves from their specific local origins both in memory and in the work processes, yet their contours never completely dissolve and thus influence the current process of perception. In this way, whether in the cinema, the gallery, the museum or an open landscape, Robert Seidel creates aesthetic intermediate spaces and locations.

www.robertseidel.com

instagram.com/studiorobertseidel

(1) All quotes in the text from an interview by the author with Robert Seidel on November 5th 2018 in Berlin.