PIX © Sophie Linnenbaum, DOP Leonard Caspari, Szeno Christina Kirk

Sophie Linnenbaum, who was born in Nuremberg in 1986, is an observer of small everyday moments and human encounters. Yet her films are not intended to be understood as pure entertainment. Nor do they let themselves be casually consumed and then founder in our memories overflowing with moving images. Instead, the filmmaker makes skilful and at time even unorthodox use of her medium in order to produce subtle thought-provoking impulses; by questioning film itself as a medium when sequences come to a dead stop, when the cinematic means are transferred to the performers, or when scene changes are not effected through editing or dissolves for instance, but rather by having the props and scenery removed from the filmic image by extras like in a theatre. In her short films, Sophie Linnenbaum surveys and queries our togetherness: “Whenever I shoot a film, it’s important for me to consider and retain the human, the humane.” It is not only on the basis of this comment that Linnenbaum’s feeling for social structures, power relations and the value of interpersonal relationships may be measured, but rather that all these aspects can be found time and again in the plots, astute dialogue and action of her filmic worlds. And these are also the aspects that the filmmaker values and appreciates since commencing her directing studies in 2013 at the Film University Babelsberg KONRAD WOLF. This university context provided her with an early opportunity to initiate cooperations on various levels and conduct intensive exchanges about the possibilities of film, as indeed about filmmaking as a practice. And already during the first years of her studies, Sophie Linnenbaum’s short films were being screened at national and international festivals. She is currently working on her first feature-length film.

MEINUNGSAUSTAUSCH © Sophie Linnenbaum & Sophia Bösch, DOP Janine Pätzold

MEINUNGSAUSTAUSCH (Duologue, 2016), a five-minute short written and directed together with Sophia Bösch, cleverly parodies the cliché about the fear of strangers and foreigners, one that “the Germans” are said to have. Looking directly into the camera, various persons talk about their encounters with “the foreigners”. It soon becomes clear that the narrative voice does not belong to the person who seems to be addressing their words directly to the viewers, but rather that the narrators are availing of the protection of anonymity to repeat stereotypical views and perceptions that become projected onto the persons in the frame. This contrasting juxtaposition of what is being said and being shown demonstrates how extreme prejudices are capable of splitting up societies.

[OUT OF FRA]ME © Filmuniversität Babelsberg KONRAD WOLF, DOP Janine Pätzold

[OUT OF FRA]ME (2016) recounts the life story of Paul from his earliest childhood, and that from the mental world of the main character. “Sometimes I wished to be like the other children,” Paul comments retrospectively and concisely on his childhood, one in which his parents’ relationship issues left no space anymore for their child, who literally falls out of the frame one day as a logical consequence of this. And that completely visually, or rather un- visually, because from this moment on Paul is only shown partially and cropped off both on photos and even in the film itself. And from this moment on, the fear of losing himself becomes omnipresent in Paul’s life. Through a fateful meeting, Paul finally becomes part of the “Outtakes” self-help group. All manners of filmic “problem cases” clash in this group: Gisela, whose life is permanently underscored with film music, Jakob, who experiences daredevil edits and thus misses out on the best moments in his life at times, and Günter, who is a classic miscast. Hannah is always in the frame whether she wants to or not, and she can only navigate through life when she is able to share the frame with another person. It seems logical that Paul and Hannah must become more intimate, yet their bond is put to a hard test by Paul’s search for evidence of his own existence. In an almost incidental manner, [OUT OF FRA]ME connects the challenges of the filmmaker when deciding on an edit, and in turn on taking the inevitable decision against this or that one, with major societal themes. In a society that shows little regard for the individual, it becomes increasingly difficult not to lose yourself.

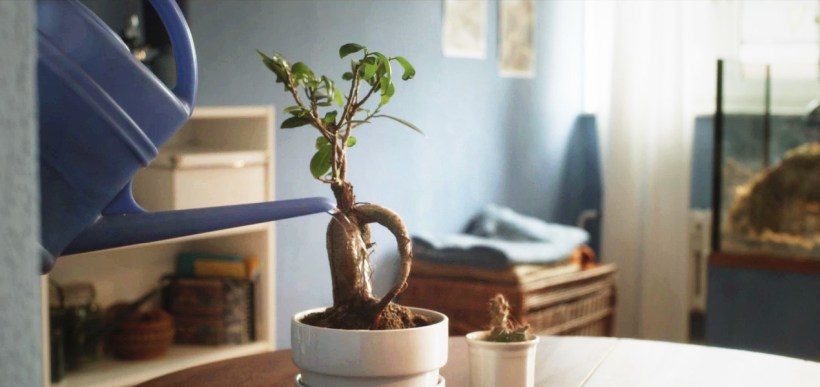

The almost 9-minute short film PIX (2017), with which Sophie Linnenbaum won the 2017 German Short Film Award, starts with a bloodcurdling scream that accompanies the final moment of a childbirth. The baby has barely landed in the arms of its overjoyed parents when the proud fledgling father holds up his camera and captures this unique moment. In fast motion, the small family’s life then unfolds before the viewers’ eyes, in ever-changing sets that are set up and broken down in the background by busy assistants, with more photos being diligently shot for the collection, quickly before each moment passes. The child’s first steps are followed by Christmas celebrations at the grandparents, followed by its first day at school, followed by one birthday after the next. And the first love is ultimately followed by marriage, an own first home and their first child. The death of the parents is followed in turn by a new life, while the framed photos on the wall preserve moments from the past, and the question remains open as to whether it is these special moments or the complete madness of everyday human existence as such that makes life so worth living.

RIEN NE VA PLUS © Filmuniversität Babelsberg KONRAD WOLF, DOP Fee Strothmann

RIEN NE VA PLUS (2017), for which she wrote the screenplay together with Michael FetterNathansky, utilises a moving portrait to describe the mental doubts of a man who is about to throw himself off a high-rise building, when a call suddenly snatches him out of the act he is contemplating. He takes the call, and the employee of a casino tells him about a main prize, for which only his signature is required. A rapprochement hesitantly occurs on both ends of the line, which is skilfully built up and timed perfectly through shot-reverse shot sequences, until yet another dramatic twist occurs in the action and Bodo’s plans begin to flounder. How far does our sense of compassion and empathy extend? How long do you remain alien, strange? The film poses such questions – and answers them in shot-reverse shots: “No one can be sad forever.”

DAS MENSCH © Filmuniversität Babelsberg KONRAD WOLF, DOP Valentin Selmke

DAS MENSCH (Pinky Promise, 2019) is part of an overall project with five fellow students from Sophie Linnenbaum’s year at the film university and it emerged from a lost bet. In all of the related films, waitresses and waiters play a role as connecting elements, while the rituals of the shared meals are surveyed and queried in completely different manners in the short films, as indeed are the relationships between the guests and the personnel. During a confirmation celebration, the tense relationships in a small family are revealed, escalating ever-more until they eventually drift off into the grotesquely dramatic.

VÄTER UNSER © Sophie Linnenbaum, DOP Janine Pätzold

Over the last two years, Sophie Linnenbaum has also turned her cinematic skills to documentaries and made two impressive films to date, in which she becomes very close to her main characters and thus remains true to her subject, the human. Taking a radically focused and subjective approach, in VÄTER UNSER (2021) Sophie Linnenbaum considers the relationships of children to their fathers. Facing the camera and placed in front of a black backdrop, six persons alternately recount their individual experiences openly. Through these individual fates, the culturally-historically charged relationships of fathers with their children become scrutinised.

NORMAL STUFF THAT PEOPLE DO © Sophie Linnenbaum, DOP Falco Seliger

It has long been no secret that the conversational tone in top-name restaurant kitchens is rough and harsh, as indeed that the route to becoming a top chef is hard and lengthy. After the years of training, switching jobs and competitions, only a relatively small field remains who can hope to achieve great fame one day. In NORMAL STUFF THAT PEOPLE DO (2021), Sophie Linnenbaum accompanies the Icelandic chef Bjarni during his preparations for the Bocuse D’Or, which is regarded as the most important cooking contest and one that requires enormous effort. As the film focuses on this lifelong dream, moments when the young man questions the route he is taking in life also slip into the scenes that Sophie Linnenbaum captures here.

Sophie Linnenbaum places the human as her subject, interacting and trapped in systems, on the stages of her filmic works. Where does the human begin and where does the film end? Does something have to end at all whenever something new begins?

Through her skilful play with genres, by falling a little out of time and back into it at the same time, by being marvellously funny sometimes and deeply sad at other times, Sophie Linnenbaum reveals that life is more than the stringing together of moments, more than the collections of photos on a wall. Also that a film does not only consist of moving images; rather, with each image that it depicts, it is even capable of making life move a little.

FILMOGRAPHY

MEINUNGSAUSTAUSCH (2016)

[OUT OF FRA]ME (2016)

PIX (2017)

RIENE NE VA PLUS (2017)

MONDAY – A GERMAN LOVE STORY (2017)

A GENTLE NOISE BETWEEN THE LINES (2017)

DAS MENSCH (2019)

VÄTER UNSER (2021)

NORMAL STUFF THAT PEOPLE DO (2021)

featuered image: PIX © Sophie Linnenbaum, DOP Leonard Caspari, Szeno Christina Kirk