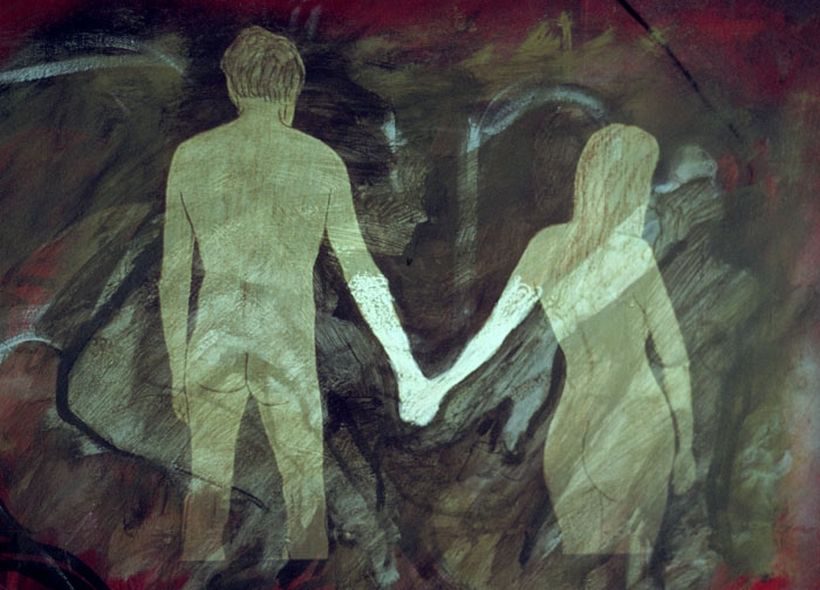

NEULICH 5 © Jochen Kuhn

If one can speak of Germany as having its own “short film establishment”, then Jochen Kuhn is by all means a charter member. He has been active as a film artist since the early 1970s, realizing his ideas in a wide range of media while always remaining true to his roots in oil painting and animation. A professor of film design at the Film Academy Baden-Württemberg since 1991, Kuhn today has nearly 25 short films to his name.

Although these enjoyed little box office success – a classic problem for German filmmakers – their critical reception was another story entirely. Already in 1981, Kuhn was honoured with the lucrative German Short Film Award for his animated film “Der lautlose Makubra”, followed by further awards at the Stuttgart International Festival of Animated Film, and the Grand Prize of the City of Oberhausen at that city’s short film festival for “Silvester”, for which he also won his second German Short Film Award. After many years of participation in countless festivals, Kuhn can boast an impressively successful short film oeuvre.

The Wiesbaden-born filmmaker, who celebrated his 50th birthday last year, confronts the widespread disdain for short film in Germany with a longstanding commitment that extends across several genres: “For me, feature films and short films are of equal value. The length of a film says nothing about its quality.” He has already embarked on the feature-film adventure twice in his career. Just how productive such a genre change can be is evidenced by his last feature film, “Fisimatenten”, released in German theatres in mid-2000. Even though the ironic, melancholy comedy, which Kuhn set in the arts scene, was shown only in few cinemas and seen by little more than a handful of art film fans, the critics were very enthusiastic. They praised the work as a “cinematic treasure” (epd-Film) that actively challenges the viewer. This is probably because the film is one of the few examples of how scenes with live actors can be deftly merged with animation to pleasant aesthetic and dramatic effect.

The concept of animated film is not always sufficient, however, for getting at the true essence of Kuhn’s works. When, for example, in his by now five-part series of everyday observances entitled “Neulich” (Recently), a painted picture is “wiped out” and a new image appears on the empty surface, this hardly seems like animation. One feels instead like an observer of a visual process of emergence and erosion, an aesthetic of vanishing. Expunging one image gives birth to another. Kuhn’s preferred palette of colours with its predominance of greyish yellow tending toward olive green subliminally evokes this idea of decomposition.

The visual level corresponds in an unaccustomed way with the content. Kuhn invites us “as viewers to penetrate into his own brain processes and to observe ourselves there as we see and complete his thoughts and watch them flow by.” This lack of classic visual continuity arouses our curiosity about what will happen next. The “Neulich” films, for instance, tell of possibilities, of everyday situations that develop their own dynamic. Out of an ordinary daily scene – waiting at a bus stop, a visit to the doctor, and all sorts of situations that can be introduced so fittingly with the gloriously vague word “Recently…” – Kuhn develops small stories with multiple options. His questioning of “What would happen if?” sometimes leads to Kafka-esque situations in which his protagonists get deeply involved in self-alienation, loneliness and the search for stability. But this dark and slightly melancholy mood is always mitigated by a quiet brand of irony and a fine sense of absurdity.

“In his films there is nothing that is not Jochen Kuhn”, commented author Sibylle Knauss. And in fact Kuhn does seem the very epitome of the independent film author, who has even taken on the entire production process for most of his films. He is painter, author, director, musician and cinematographer, and works in his own studio. Only editing and sound are left to his long-time associate Olaf Meltzer.

In order to preserve his financial independence in the face of erratic film funding and predominantly youth-oriented grants, Kuhn supplements his earnings by teaching. This is the same path taken by many of his colleagues – we need only think of Matthias Müller who, despite resounding international success, has taken on a post as professor of experimental film at the Cologne Academy of Media Arts. One can conclude that the resourcefulness demanded by this kind of patchwork biography is just what is called for in this era of shrinking cultural funding in Germany. This has not been lost on Jochen Kuhn, one of the nation’s most interesting animated film makers.

Biography and filmography are available at http://www.jochenkuhn.de