How web series are breaking the fourth wall to become series

DRUCK: funk adapted the Norwegian SKAM into German and its multimedia storytelling. © Gordon Muehle

People are viewing films and series on their smart phones. There, I’ve said it. It makes the eyes of cinema purists well up with tears of wrath, but a long underrated format is finally stepping into the limelight: The web series.

Of course, web series did not first appear with the advent of LTE and 4-inch display screens, but the transformation in how and when we consume audio-visual content[1] – or rather our gaining of the technological capacity to consume it everywhere – has acted like fertiliser on carefully tilled soil. And web series have thrived to become the new superfood of the industry. An industry that is well advised to finally detach itself from linear output channels and their narratives and accept that the internet is the next logical stage in the evolution of television. Just like television once was for the cinema.

“Wow, it’s really well produced!” No shit, Sherlock

Web series are series, or stories in other words, that we consume via the internet. Attempting to define them as a format or even as a genre is a futile and nonsensical undertaking, as the sole quality or characteristic that all web series have is their place of release. And the prefix web, as an indication of where the series appears, will – in a digital world – soon merely be redundant. Yet for that, the oft-quoted 2012 definition from the media scientist Matthias Kuhn still remains true:

Web series are audio-visual formats on the internet that are characterised by their seriality, fictionality and narrativity, and have been produced for the web as their first place of release.[2]

This definition just has to be readjusted or pried open. Fictionality is no longer a must for a web series, with documentaries also viewable on the web in a series format. And the meaning of what is termed “serial” in an entertainment programme is also undergoing transformation. At the latest since BBC’s Sherlock, a series season no longer requires either a minimum number of episodes or regular intervals between the season premieres. Not to mention a broadcast slot punctually at the start of the traditional series season. Likewise, the term web series requires some further adjustment with regard to the public perception of them. Web series are overly defined there as being coexistent with the current film and TV industry formats. With newspaper arts sections and industry journals surprised by their high quality, authentic stories and good non-professional actors. In web series, they see a kind of preschool class, in which experimentation and play is enabled, until a chosen few are permitted to move up to the big group. Are they not aware that, technologically speaking, every Netflix original is a web series? This label is the narrative of an aging generation and outdated tradition of linear programme makers who want to retain their big player status, yet are now obliged to reacquire territory. But the paradigm shift is in full swing.

giphy.com © BBC/via Sherlock on GIPHY

Webs Series for Everyone!

Web series are displacing the old formats. And not only because we are now watching everything on the internet and are able to upload everything there cost-free, but also because the public would itself like to determine and produce which stories it wants to see. And for several years now, it has even been able to achieve its will here. There is no technological monopoly anymore. With smartphones and 4K cameras, many users have access to the latest quality standards.

giphy.com © via Urban & Uncut Studios on GIPHY

Distribution options or broadcast licences have long ceased to be the thresholds for people to release and disseminate their own stories. The rules of the game for this are set by social networks, self-publishing platforms and content networks. Here in Germany, YouTube in general and especially the funk content network from the ARD and ZDF public TV broadcasters – aimed at 14 to 29 year-old audiences – play the most important role in the distribution and production of web series.

And then Came Wishlist

© Outside the Club

funk produced Wishlist (2016), the industry game changer, and instead of screening the series in the best TV broadcast slots or via its media centre, it was released directly on YouTube. Go where the audience is. Fortunately, not only was Wishlist very well produced (in 4K), it was even exciting, thankfully. A teenage thriller about a mysterious app and with melodramatic characters – this is what German audiences expect from Anglo-American productions, but never from the predictable, format-fixated German film industry. And everyone loved it: With just under 143,000 channel subscribers and 6-digit viewing numbers per episode, even the respective stakeholders then became convinced that this web series could become something. And after Wishlist went on to win the Grimme Prize and the German Film Award, the format even appeared on the radar of the last traditionalists.

giphy.com © via funk on GIPHY

But enough about the media philosophy and the breakthrough achieved by web series in Germany. Let’s now take a look at a few successful examples and how web series have managed to break through the fourth wall.

A Norwegian Lady Was Listening

The Girls: Kiki, Amira, Hanna, Mia und Sam. © Johannes M. Louis/ZDF

The great thing about web series and their jettisoning of linear output channels is their spreading out onto the most diverse social networks and the adaptation of the format to the distribution opportunities. Or was it the other way around?

Let us take DRUCK (2018), the latest web series coup from funk.[3] In it, Berlin students in their final schoolyear are struggling through relationships and exams in a process of self-discovery. DRUCK recounts exciting and important stories from the everyday lives of adolescents[4] with convincing dialogue and finely drawn three-dimensional characters. At first we are sitting in a relationship rollercoaster with Hanna, then we find ourselves squeezed into Mia’s oppressive feminist shoes. In the current third season, we are discovering our sexuality together with Matteo.

The Boys: Jonas, Matteo, Abdi und Carlos. © Richard Hübner/ZDF

Doing so, the series manages to get incredibly close to its audience thanks to its skilful dramatic compositions and the way it avails of the output platforms. Each season, the protagonist changes and the series’ identification figure in turn. Each episode consists of sequences that begin with the stamp of a weekday or daytime. Over the course of a season, the sequences are then released on YouTube exactly on their weekday at the intended daytime. In this way, the impression is created of being able to follow the events occurring around the DRUCK protagonists at first hand and in real-time. These one to seven-minute sequences are then combined once more into half-hour episodes, which you can binge-watch later on. Moreover, each figure has their own Instagram account, on which the fans are able to see and comment on what the figures are speaking about. (“Sara posted that you’re a total jerk.”) The related fan content is available additionally via the DRUCK WhatsApp chat.

giphy.com © via funk on GIPHY

How do you come up with such user-oriented output? By listening. Julie Andem, the creator of the original Norwegian SKAM (“Shame”) interviewed teenagers on their opinions about religion, politics, love, their everyday experiences, their favourite apps and how they use them. In addition, she took note of the commentaries under each new SKAM episode and let them flow into the subsequent episodes. The fourth wall vaporised.

Apart from their highly impressive stories, both SKAM and DRUCK represent prime examples of audience interactions that to date have been reduced too often to click counts and coverage reach.

Sharing is caring

© Arte/BR

Contrary to Kuhn’s definition, web series also work as non-fictional formats. With Einfach gut leben (Simply Live Well) (2018), the Arte cultural TV broadcaster produced a seven-part documentary series on the subject of “unconditional basic income” that explores the triangular relationship of work, money and life in seven different countries, cohabitation relationships and views of life.

© Arte/BR

Although the single episodes can be accessed in ARTE’s media centre, the best way to use and view the web series is via their homepage. A question and answer game – designed as a rudimentary point and click quiz – guides the user through the series. Their answers determine the sequence in which they view the episodes. Doing so, situations in the previous episode are taken up again and lead to the next one. In this way, a discourse arises spontaneously between a user and the series. And not only is the content consumed, but even processed.

Stories via Stories

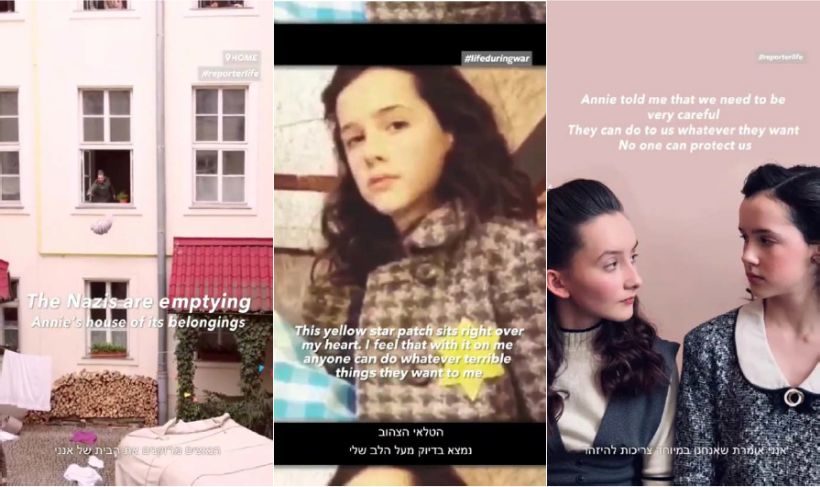

© Screenshot Instagram @eva.stories

Fiction and historically proven facts are combined in The Girl with the Instagram – a web series that occurs completely on the eva.stories Instagram account. Eva Heymann was a 13-year-old Hungarian who was transported to Auschwitz in 1944 and murdered there. From February until her deportation in June ’44, Eva wrote a diary. In order to make her story and the Holocaust accessible to a young generation, the Israeli billionaire Mati Kovachi transferred EVA’s diary onto an Instagram account. With the entries becoming Insta-Stories. Performers act as Eva, her family, her best girlfriend and the Nazis.

© Screenshots Instagram @eva.stories

Unlike with the other examples mentioned, the platform determines the design and format of the visual material directly here. Instagram is an app for mobile devices only. And Insta-Stories is a feature intended to permit the posting of images and videos in real-time. For which reason, we see the stories in an upright format, divided into 15-second snippets, shot on a smartphone and with a shaky display – because Eva films everything. In 70 short films, we see her at her birthday, fooling around in class, the emergence of the Nazis, sewing on the yellow star, the mass accommodation, the last jar of jam, the train to Auschwitz. Despite the awareness that actresses and actors are being viewed here, as well as the distance created through the costumes and setting in the 1940s, we are able to perceive and experience Eva’s story. And this is achieved especially through the usage, functioning and intention of the Instagram app.

Representation, Baby!

What else can web series do better? Representation. In the main TV programming, adequate representation of queer characters[5] or the casting of people of colour (POC) has always been lacking. In the USA especially, web series play a critical role in filling this gap, with the best examples being: Issa Rae’s Awkward Black Girl (2011) or the Emmy nominated Her Story (2016).

© funk/DFFB

With Straight Family (2018), funk has made a good effort at providing a gay-lesbian series here in Germany. The first season consisting of five episodes is devoted completely to the subject of coming out in the family and has garnered praise for its dialogue, as well as for the conspicuously inconspicuous representation of homosexual people. Straight Family was not made in cooperation with a production company, but rather with the German Film and Television Academy Berlin (DFFB). Four female directors and seven writers recommended a queer theme and produced the stories centering around Lara (lesbian) and her brother Leo (gay). Doing so, they also cast queer actors.

© Screenshot Polyglot, Episode 1 von Amelia Umuhire

With Polyglot (2015), Amelia Umuhire created a three-part gem. Amelia comes from Ruanda, grew up in Neukirchen am Niederrhein, studied in Vienna and then finally moved to Berlin. As it accompanies Babiche, who raps and would like to find a room in a shared apartment, Polyglot (“multilingual person”) deals with arriving in a new place, homesickness and the great question of identity. Polyglot was created spontaneously over one weekend in Berlin for a YouTube video competition. Dispute this, it manages to delve down metre-deep into its protagonists, although they are merely observed. There is no rigorous dramatic composition; only slivers of different situations, a minute aspect of a personal story and the filmic design adapted to this. When necessary, this consists of a steady camera or a chilling collage from surveillance videos.

Until Eternity

Web series, or series as we now call them, are starting to become aware of their possibilities. Are starting to understand about introducing and inserting their audiences, and realising that they are capable of achieving everything. Not just the TV thriller on Sunday night, or the intensive TV movie, or the Netflix original – but their very own stories.

© Arte/BR

Show us your versions of these stories. We want to see them.

[1] Close your eyes and point randomly at a study. Every one of them states that smartphones are replacing laptops and PCs and that videos are the preferred consumption format. Like here or here.

[2] Kuhn, Markus (2012): “Between Art, Commerce and Local Colour: The Influence of the Media Environment on the Narrative Structure of Web Series and Classification Approaches”, in: Nünning, Ansgar/Rupp, Jan/Hagelmoser, Rebecca/Meyer, Jonas Ivo (Eds.): Narrative Genres im Internet. Theoretische Bezugsrahmen, Mediengattungstypologie und Funktionen. (Narrative Genres on the Internet. Theoretical Reference Framework, Media Genre Typology and Functions.) Trier: WVT, p. 51 to 92.

[3] DRUCK is a German adaption of the Norwegian web series SKAM (2015). The characters, plot, visual language and design, as well as the distribution concept were assumed from the Scandinavian model. Further SKAM adaptations have been produced to date in the Netherlands, Belgium, France, Italy, Spain and the USA.

[4] Mental health, love, trust, friendship, self-awareness, sexual harassment, abuse, transgender, sexual orientation, religion, exclusion, bullying, jealousy, family stress, alternative lifestyles, adulthood, drug consumption, pressure to succeed, fear of the future.

[5] As persons, not as eccentrics.