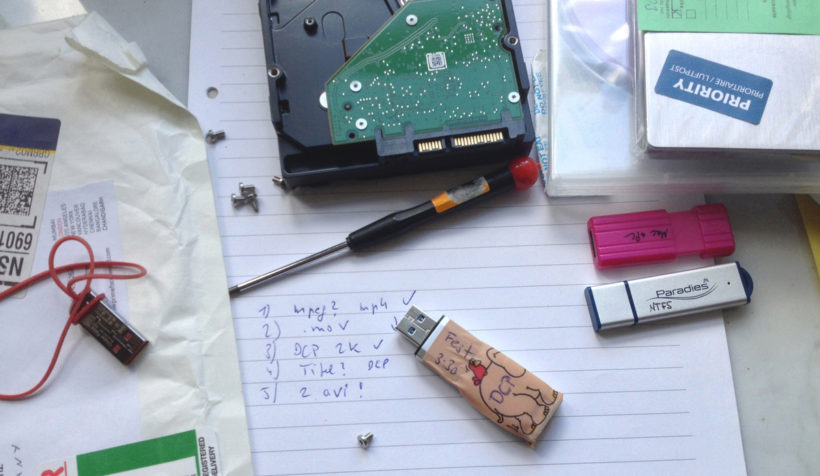

Just unwrapped: Short films on various data carriers @ rww

The digitization of cinema initially aroused hopes that short films would be able to make their way to the big screen much faster and at lower cost – without sacrificing quality. Unfortunately, this dream has not become reality. If you ask cinema operators, festival organizers and in particular projectionists about their experiences thus far, you’re likely to be greeted with a loud groan. Particularly when it comes to short film, the variety of formats has proliferated to such an extent that adapting them to varying projection conditions can turn into a nightmare. This applies especially to events screening films acquired directly from the manufacturer and not through a distributor. Most film festivals have of necessity adapted to these changing conditions, but cinemas are lagging behind. Today, nearly all festivals have their own technology departments that spend weeks preparing for screenings, ironing out errors and creating the required screening copies. But the effort and stress involved could be reduced substantially by taking into account just a few key factors. And that’s what this article is all about: namely, how filmmakers can assist with mastering the chaos of digital formatting.

The effort required to settle on a single projection format is particularly high in the short film sector, because shorts are usually shown in programme blocks, meaning that the projection system cannot be switched between films while the audience is kept waiting. What’s more, as mere event organizers, festivals are wholly reliant on the technology used in ‘their’ festival cinemas and venues. They therefore have the task of checking into the local technical specifications and communicating them to the participating filmmakers. But because short film makers are usually unable to afford special service providers that are able to meet the given specifications, they are left to deal with this challenge on their own. In one respect at least, their fears can be laid to rest: although the specifications differ from festival to festival and from cinema to cinema, there are some viable strategies for finding common denominators. What’s required is a good understanding of the material and some basic knowledge of what screening digital copies involves.

As an introduction to this topic, the following summary outlines the specifications for data carriers, container formats, codecs and a few other factors. I won’t go into all the details, but rather proceed in a solution-oriented manner by addressing only those that are truly essential. These recommendations are based on a survey of festivals and my own (painful) experiences with short film programmes at the cinema.

Tips on hard drives and alternative data carriers

The preferred physical carrier for digital films is a hard drive in a sturdy housing. Before a film is copied onto a data carrier for shipping, a decision must be made on how to format the drive, because every operating system and every playback device has its own standards and proprietary file systems.

DCI compliant Digital Cinema Packages (DCP) are the standard for theatrical distribution. For films in DCP format that are to be transferred directly to a film server (so-called ‘ingesting’), drives with the Linux file system are the best choice. Recommended here is ext3 (not ext4) and an INODE size of 128 bytes (not 256). This is important for non-Linux-based film servers such as Ropa Cinesuite and alternative e-Cinema systems. But it is also the DCI standard. 2K DCPs (not 4K) are recommended as the lowest common denominator for nearly all film servers. And if the hard drive has the faster eSata interface as well, the projectionists will rejoice, because they will save a lot of time ingesting!

Most film servers can also read out NTFS-formatted hard drives, so you’ll usually be on the safe side with NTFS (a Windows file system). MacOS file systems are generally unsuitable for DCPs. Although it is possible to copy files from a file system to a drive that is formatted differently, this entails added work and carries the risk of read/write errors. By the way, film servers will also reject the ingesting process for copy protection reasons if the copy is not bit by bit absolutely identical to its original (hashsum verification).

Memory sticks have the advantages of compact size (inexpensive to buy and ship) and compatibility regarding operating systems. They also eliminate the need for a cable and power supply. Commercially available sticks are suitable only for very short films, however, because their partitions in FAT32 format can store only data packages up to 4 GB in size. Sticks can however also be formatted with the above-named file systems and then be used to store even larger files.

But there are good reasons for choosing a hard drive instead: memory sticks are fragile (housing, plug) and slow. Also, they are too small to be properly labelled. Some festivals (for example the IKFF in Hamburg) still prefer sticks, though, because they’re so handy.

Alternatively, films can be burned as data files on Blu-ray disc or DVD, but only if this is expressly accepted by the festival. Important is that the disks are labelled as data carriers so that they are not mistaken for a playback medium.

No matter which data carrier is used, it’s a good idea to copy the data back once before shipping and then test the copy of the film. The package sent to the festival or cinema should include a list specifying the film title, file name and technical specifications (container/codec).

An alternative to physical shipping is to upload the film to an online storage network, if this is offered by the festival.

Packaging digital data correctly: container formats

The container format refers to the container that holds the video and audio streams, metadata and any subtitle lists. Common examples are .mov or .mp4 containers, although the Quicktime format cannot be played back directly by many festivals or cinemas. The container format for video and audio streams in DCPs is always MXF.

No festival or cinema is able to play all existing container formats directly. All films in a programme block should have the same format. This is the only way to compile a trouble-free playlist (show).

In the short film sector, the introduction of the DCI (Digital Cinema Initiatives) standard for DCPs is more of a problem than a solution to the question of format. Few of the smaller cinemas and cultural venues, let alone pop-up cinemas, can afford the extremely expensive equipment needed. And film manufacturers face much greater effort and higher costs for producing DCPs. Most short films are made in HD resolution and lower, possibly even still in 2K. Hardware media players, which are inexpensive to purchase, would then suffice for playing MP4 films in HD. Interfilm Berlin has developed an interesting solution for this problem, which has also been used occasionally at the festivals in Hamburg and Clermont-Ferrand.

Compression: codecs

Video codecs are electronic circuits or applications that encode the data stream and decode it again when the film is played back. Codecs are used to reduce the amount of data. They are ‘lossy’, meaning there are some losses in image quality – which are more or less apparent depending on the setting used for the encoding.

When producing DCPs, the motion JPEG 2000 image compression algorithm is used. One feature of this codec is that it calls for 24 frames per second, because it compresses only individual frames. For displaying movement, this is better than the usual compression through omission of similar content in image sequences. However, in all countries with a 50 Hz electricity grid, a frame rate of 25 fps is the rule for electronic images (US: 23,98/29,97). Therefore, anyone making their own DCPs has to make sure that image and sound are transformed into 24 fps!

No codec is equally suitable for all areas of recording, editing, post-production and projection. Just like with the containers, each operating system has its own codecs. As Apple is the most widespread operating system used in post-production of short films, H.264 and Apple ProRes are semi-standards.

H.264 or the Open Source variant x264 are too computation-intensive for editing systems, but very well suited for playing films. H.264-compressed films are accepted by all festivals. Festivals that play files instead of DCPs usually demand H.264 or alternatively MPEG-4-encoded files in mp4 containers.

Apple’s ProRes is suitable for both post-production and further processing. This is because the codec is able to cope with up to 8K resolution at relatively low data rates. But it is not suitable for playing films. ProRes is preferred only by festivals that produce their own files or DCPs for film screenings. In this case, it is also irrelevant that ProRes is typically packed in .mov containers, because the film will be transcoded anyway on a Mac for playback.

Tip: For filmmakers, ProRes files in Quicktime containers are best as source format for any possible subsequent conversions (as a kind of digital inter-negative).

Picture power: bit rate

The bit rate describes how much data can be transported in a given amount of time. The unit of measure is bit/s, or bps. If the bit rate is too low, quality suffers (causing, for example, a weak picture). If it is too high, too many units of information are dispatched simultaneously, which typically leads to a jittery image. How many bps a playback system can cope with depends on the processing power of its components and, in networks, on their bandwidth.

For DCPs, the DCI standard recommends up to 250 Mbps; however, some film servers (or projectors) are unable to cope with this maximum bit rate. The recommendations of the festivals range between 150 and 200 Mbps with a variable bit rate. The reason for this recommendation below the standard is not only the varying facilities available to festival cinemas but also the amount of data to be managed. The higher the bit rate, the larger the file, the longer the ingesting process takes and the more disk space is required.

For files that are transcoded by the festival, there are no uniform recommendations. The best bit rate for files (except for DCPs) that are played back in an unprocessed form depends on the performance of the playback devices used (computers or hardware media players). The following guidelines will usually apply, however: For a resolution of 1080p, up to 20 Mbps will be sufficient. And for 720p, 10 Mbps will be enough. These values are incidentally at the upper limits of what is specified by online platforms. In this case, therefore, filmmakers can save themselves the trouble of creating various differently formatted copies of their film.

Easier in comparison: sound

Unlike the video stream, the audio stream with its modest amount of data poses few problems. Audio can be delivered uncompressed (‘lossless’). Bit rates of up to 1.5 Mbps are unproblematic. A typical setting for playback would be: lossless 48 kHz at 1440 Kbps with Apple Audio Codec (AAC) or PCM/WAV.

Sound problems will be encountered, however, if the audio stream is delivered in 5.1 Surround and the cinema does not play films from servers equipped with Dolby processors. For such cases, it is advisable to mix the sound in stereo. Then there will be no unpleasant surprises, such as the complete failure of a vital sound track.

Warning with regard to subtitles

Nearly all festivals prefer ‘burnt-in’ subtitles that are part of the image – in contrast to separate subtitle documents that must be synchronized during projection. This is actually a disadvantage, because some containers, in particular DCPs, can contain multiple subtitle lists in different languages which can be freely chosen or also hidden during playback. A single version of the film would hence be sufficient for use in several countries (Original with Subtitles) and at home (Original Version). However, separate subtitles that are not embedded properly are a common source of error. Subtitles might also run asynchronously or contain font tags that cannot be interpreted by all servers. Even big-name DCP manufacturers make mistakes like these!

Different picture formats may not fit into a single masking frame

Image formats are also critical, in other words the aspect ratio and the horizontal or vertical resolution. Ever since digitization, the old analogue standards such as normal, widescreen and scope no longer apply. And where they do exist – for example DCPs in flat (1:1,85) or scope with fixed pixel values – errors can occur, for example in the transcoding of films that were originally shot in HD 16:9 (1:1,77). Most cinemas have vertical movable masking panels (at a fixed height) to compensate for varying widths, but the zoom can of course not be adjusted to varying heights for different films shown in one programme. Here as well, filmmakers must declare what is required, because otherwise how is a projectionist to know whether the film is to be shown square, anamorphic or in Superwide-Scope with Letterbox?

Workflow – festival production

As too many filmmakers do not comply with specifications, festival organizers have begun to analyse all submissions and to transcode films that do not fit their playback system themselves. In the days of analogue cinema, it was sufficient to pass the film through a rewinder and check the copy by hand, and any required format changes could be made during the screening. In the digital age, however, an additional, highly specialized field has opened up for comparable work. Preparing films has become much more time- and personnel-intensive. This means that several assistants with very specialized knowledge are required (digital technology, IT, mastering, projection technology).

A typical workflow might in short look something like this: Cataloguing of incoming or downloaded films in a database, storage on a central server, analysis of the formats, consultation with the filmmakers if anything is unclear, transcoding onto the festival’s own system, recording of work processes to keep colleagues informed, copying films to the festival’s own hard drives or media players, transporting them to the cinemas, ingesting into the local film servers, creation of playlists for each programme block, and finally an on-site video and audio test. This extensive workload begins up to six weeks before the event – work that can be nerve-wracking if filmmakers don’t follow the ‘rules’!

Don’ts: From my own experiences in daily cinema work

Last year, the short film programme of a student festival was held at our cinema. The films were left with us without being checked first. The packages we received held DCPs on memory sticks and hard drives, files on memory sticks and data discs as well as screening Blu-rays. Of the 12 films in the programme, only three were in a form we could use directly! Of five DCPs, only two were playable at all (errors in the folder structure or the composition play list). One DCP caused a crash that paralysed the film server. Two different films appeared on the server under the generic name ‘AnnotationText’ and one file was simply called ‘myairbridge’. Most bizarre of all was a DCP that was divided into two compressed archives in .rar (!) format and then burnt onto an unlabelled data Blu-ray … All in all, we really had a lot of fun 😉

How to cause festival staff the most aggravation …

- Do not read the technical specifications or do not try to comply with them.

- Never label a hard drive, because it mars the look of the housing.

- Send a link for downloading the film but no password (it’s a secret after all).

- Call the file ‘MyFilm’ (seeing as you’ve already indicated the title on the entry form).

- Start off your film with two minutes of colour bars and black and a countdown (proving you’re a cinephile who knows what professional video tapes used to look like).

- Do not include any written information about codecs, container format, video or audio format, because you already said on the phone that the film is in the normal format and you don’t understand all that stuff anyway.

- When your film is to be shown, bring a new version with you on your laptop that you would like to test right away.

Best practice

- Read the technical specifications and ask about anything you don’t understand.

- Get professional help if you encounter difficulties.

- Only make a screening copy, or have one made for you, after addressing points 1 and 2.

- Include with your film a ‘leaflet’ with the technical specifications, including the above-mentioned factors (container, codec, bit rate, video and audio format) and indicating any deviations from the festival’s specifications.

- Before shipping: Do a test screening at a friendly cinema.

- Deliver the film before the specified deadline for screening copies.

- Ask the festival if everything is okay (no later than two weeks before the festival, because by the week before at the latest everything has already been set up).

- Have a relaxing trip to the festival, treat the projectionists and festival producers to a beer, and enjoy the screening!

Reinhard W. Wolf