One of the many recent upheavals in the film and festival world, in this case caused or presumably accelerated by the pandemic, involves the expansion of festival activities beyond the traditional festival period.

It is simply astounding how quickly one festival after another is embracing this trend – regardless of size and profile. Festivals both large and small – whether with a documentary, feature or short film focus – are today extending their programmes beyond their usual time and place to present offerings both online and at the cinema. Festival tours have been around for a long time, but more recently festival programmes are also being rerun at cinemas after the fact, or festivals are putting on satellite events in other locations or even other countries. In addition, films from supporting programmes are rerun or streamed either during or after the festival. The above-descried activities are presented as pre-festival, online festival, pre-game or post-game.

It is difficult to tease out a unifying concept here or a common strategy. Rather, it seems that anything goes at the moment. It is an open question anyway whether film festivals today can still agree on a common mission or are expected to follow a consistent formula. More interesting and important is the question of how they are reacting to their different social, cultural and economic environments to find new solutions that nevertheless remain true to their ideals and the expectations of their guests. Today, no two initiatives are the same, just as the festivals are not equivalent either – each has its own cornerstones and history. What they all have in common though is that they are currently extending their reach in space and time.

Year-round

In Germany, a media arts festival, transmediale, has taken the most drastic step. Originally presented by a media workshop as an alternative video festival, it was timed to coincide with the Berlinale, but in 2021 the organizers announced that the festival would now be presented year-round. Instead of putting on a five-day event at the Haus der Kulturen der Welt as before, various formats were scheduled throughout the year, taking place – surprisingly for a media arts festival – predominantly in analogue physical form.

“For the first time since 2001, the transmediale will not be staged at the Haus der Kulturen der Welt, but will take place online and at selected sites in Berlin as a multipart event programme. In addition to international residencies, workshops and commissioned works, the 34th edition will feature an entire year of exhibitions, film screenings and a discussion programme that investigates the material, technological and cultural aspects of refusal from a critical-reflexive and interdisciplinary perspective.” Nora O Murchú (artistic director of the transmediale)[1]

“In her opening greeting, O Murchú emphasizes that this decision is due not only to the pandemic but should be seen as a response to the ever-increasing pace of cultural production and consumption.”[2]

Home Delivery Service[3] – simultaneous and hybrid

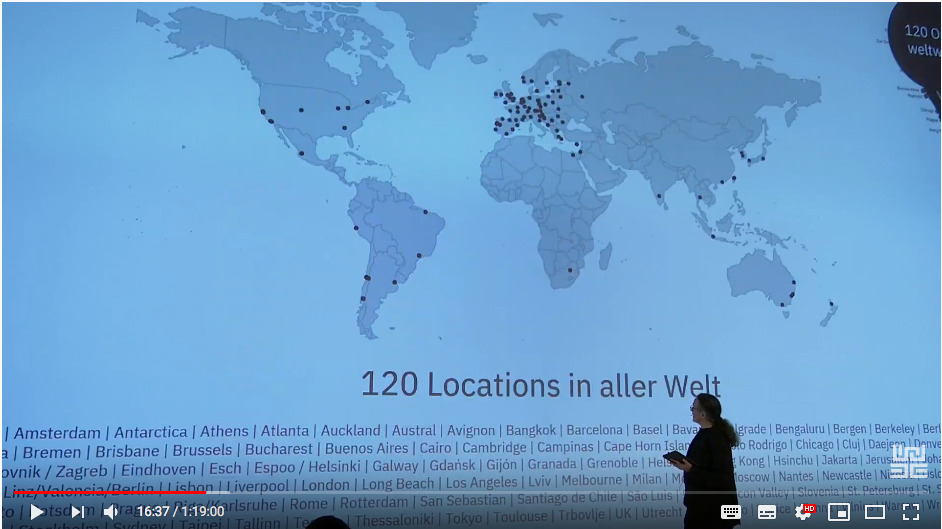

By contrast, the Ars Electronica media art festival in Linz, Austria, which is much more strongly influenced by digital cultural practice than transmediale, took place in 2021 “physically not only in Linz but all over the world – dozens of partner institutions around the globe will open their Ars Electronica Gardens with their content, which can also be experienced via the Internet as the hybrid Ars Electronica from September 8–12, 2021.”

Ars Electronica Pressekonferenz 2000

To demonstrate the expansion of the festival, a key visual from 2021 showed a world map with sister cities on many continents. As a stage backdrop for the on-site events, the image manifested in sheer monumental fashion the festival’s global claim.

The key visual for 2022 takes things one logical step further and shows planets in space. Linguistically, the expansion is evoked in programme titles such as “Deep Space” and “Planet B”. The term “Home Delivery Service” for the festival’s educational programme is very apt by comparison.

Noteworthy, however, is that Ars Electronica did not extend its activities in terms of time but adhered to the traditional festival week (8–12 September 2021).

Noteworthy, however, is that Ars Electronica did not extend its activities in terms of time but adhered to the traditional festival week (8–12 September 2021).

Similarly, the International Short Film Festival Oberhausen limited the screening of competition films to a fixed festival period. Since 2021, though, there have been separate online and cinema competitions. As it is not possible to submit films to both, filmmakers had to/ were allowed to decide between the two in advance. In 2022, the competitions were held at different times, with the online versions running before their on-site counterparts. This gave festival-goers the opportunity to view all the competition films. The festival took place on site for the same period as before the pandemic. However, exclusively youth and children’s film competitions were held on the first and last days of the six-day festival. The on-site German and international competitions were each shortened by one programme. The running time of the films on the four additional days of the online programme corresponded to about one and a half additional German and four additional international competitions. The festival thus expanded both its programme volume and programme period.

Online extension

Oberhausen’s programming was then extended for a significantly longer time through its participation in the three-month online European short film programme THIS IS SHORT.[4]

Among the short film festivals expanding only their online offerings is the Bamberg Short Film Festival, which showed competition films online during the 2022 festival and for a week afterwards. The Monstronale Halle festival did likewise, offering films on the platform Filmchief for ten days post-festival.

In 2021, DOK Leipzig also opted for a time extension on the internet. While the 2020 festival had been planned as a hybrid event, the festival did not continue its streaming offerings until after the festival week was past, from 1–14 November.

Of the German short film festivals, interfilm prolonged its online presence to the greatest extent. After the physical festival took place on the traditional dates, with seven screening locations in Berlin, interfilm 2021 put its complete programme online for almost a month in cooperation with the VOD platform Sooner (formerly realeyz). As a new addition, the festival also held an online-only competition with audience voting “in advance” of the festival.[5]

Virtual hubs as a special case – expanding into the metaverse

Some film festivals use so-called virtual hubs to allow their guests to communicate with each other, but only a few have embedded content, let alone video streaming there. After the innovative Festival Internacional de Cine Guanajuato in Mexico (see report [6]), led the way in 2020, this year the Stuttgart International Festival of Animated Film also took a step in that direction. As part of the German Federal Cultural Foundation’s project “dive in. Programme for Digital Interactions”, the festival developed its own project called “ITFS & Raumwelten VR Hub”. In the Hub, visitors can meet and interact as avatars in reconstructions of real festival locations or in a lounge or digital workshop rooms. The ITFS VR Hub also hosted streaming events in 2022. For example, the open-air programme on Stuttgart’s Schlossplatz was broadcast live to the Hub cinema.

Online year-round

A pioneer in year-round programming is the LGBTQ+ film festival Frameline in San Francisco. Now in its tenth year, the festival is putting “Frameline Voices” online, a 12-month programme of short films. Frameline Voices was originally intended as a programming offer for cinemas. However, with the exception of its own festival cinema, the “Castro” in San Francisco, the initiative was not a great success because other cinemas were not eager to screen the films. Over the years, the programme has evolved into its current format, easily accessible to all for free on YouTube. But the filmmakers do not ‘go empty-handed’. The festival actually pays a screening fee for the selected films!

Very recently, Frameline also launched “Streaming Encore”, which, after the June 2022 on-site festival, will show 69 programmes, including nearly 80 short films, in an online rerun – but in this case with geoblocking, so that they can only be viewed in the USA.

The Tallinn Black Nights Festival PÖFF likewise offers year-round online activities, in technical cooperation with Shift72, as does the NH VOD of the New Horizon Festival in Wroclaw, in cooperation with Springer Polska – to mention only two examples on which we have already reported in the past [7].

Activities and satellite programmes in cinemas throughout the year

Individual programme reruns at a festival’s home location as well as touring programmes have of course been around for a long time, as mentioned above. But these activities have been greatly expanded bit by bit. Initially, film festivals used such offerings to keep their regular local audiences warm throughout the year, for example with open-air summer cinemas, or to reach out to new groups of viewers.

Travelling festivals that screen the same programme at different locations have also been around for quite some time. Rather than being based at a central location at a certain time of year, they were conceived from the start as travelling shows. What is new are satellite programmes that were initiated with a view to minimizing the risk of cancellations during the pandemic while reassuring donors and sponsors by spreading out geographically and over time. Prime examples are the Sundance Film Festival and, in Germany, the Duisburger Filmwoche. The latter was unlucky in its first attempt at launching satellite programmes [8] in 2020, as only one site (in Switzerland) was not affected by a lockdown. However, the festival persevered with the idea, and a recent programme took place this year at Berlin’s Arsenal cinema. Sundance for its part scheduled so-called “Local Lens” programmes in its own state as well as appearances in film hotspots across the United States. Sundance, too, has remained true to this concept and recently (9–12 June) hosted a Sundance Film Festival in London, for example – including two programmes of shorts.

Regularly recurring activities at the cinema

It is noteworthy that since pandemic-related bans on large gatherings have been relaxed, the amount of off-festival activity in physical locations has significantly exceeded that on the internet.

The number of festivals that schedule regular rather than only occasional events is steadily increasing. A few examples: The KFFK/Short Film Festival Cologne launched a KFFK “Short Monday” at the Filmhaus Kino in January 2022, exground regularly shows a “Film of the Month” at the Kommunales Kino Caligari in Wiesbaden, and the Rotterdam Film Festival presents a programme every first Wednesday of the month at the Lantern cinema (where the IFFR was founded). The Stuttgart Festival of Animated Film presents programmes of selected films from previous festival years on the last Monday of each month at Stuttgart’s downtown cinemas.

The high proportion of documentary film festivals and thus documentaries among the off-festival screenings is striking. The Duisburger Filmwoche has already been mentioned above with its satellite programme. Other prominent examples from Germany include the Kassel Dokfest and DOK.fest Munich. Under the title “365 Days of Documentary Film”, the Kassel festival presented one film each month with guests and film discussions at the cinema [9]. This was similar to the strategy of DOK.fest Munich, a very large festival in terms of both its offline and online reach, with its year-round cinema programme DOK.aroundtheclock [10]

Taking a closer look at the selected titles, it is noticeable that they are almost exclusively films without distribution. In retrospect, these films, with the exception of a few titles, did not find a distributor later either. For producers and filmmakers, this situation is at once gratifying and regrettable. Gratifying, because the films are being shown on the big screen. And regrettable because they have no nationwide theatrical release and are featured only at one-day events.

In terms of film promotion policy, the extensions beyond the core festival period attract funds that are not part of the usual film funding system. To my knowledge, Austria is the only country that explicitly mentions physical “satellite events” as an objective for its state (festival) funding [11].

From the point of view of cinemas that cooperate with festivals year-round, such events make for interesting programming and are even lucrative, as festivals pay rent for the use of the cinema. These programming concepts allow culturally oriented cinemas to expand their offerings to include events with guests and film discussions – features that are part of the core mission of Kommunale Kinos in Germany, for example, but which they would otherwise be unable to provide due to lack of staffing and insufficient institutional funding.

Festivals thus assume the usual functions not only of distributors but also of arthouse cinemas (without having to operate, let alone build venues themselves [12]). Optimistically, it can be assumed that these developments will open up paths to greater global visibility and distribution for films that would otherwise not enjoy such opportunities, and that the programmes will attract new cinema audiences. But that is not yet a foregone conclusion. Serious scepticism was already raised several years ago. Cultural critic Paul Willemen charged that in reality film festivals only create a “bottleneck effect”, ensuring that non-commercial films remain outside of official distribution channels. Meanwhile, traditional distribution channels were reserved for mainstream blockbusters. “Festivals”, says Willemen, “don’t bring cinema closer to the people. On the contrary, they encapsulate and isolate films, shielding them from a wider audience and thus effectively reducing any chance of proper presentation”[13].

If the momentum continues as described above, it will have far-reaching consequences for the film and cinema landscape. Only festival studies and the future will show which consequences those are.

[1] Nora O Murchú (Artistic Director) (https://www.kulturstiftung-des-bundes.de/de/projekte/film_und_neue_medien/detail/transmediale_2021_22.html).

[2] 2021 https://www.art-in-berlin.de/incbmeld.php?id=5639 (in German)

[3] “… all kinds of exciting offerings for schools, universities and companies – all of this is ‘Ars Electronica Home Delivery’. Whether you’re at home in your living room or office, in the classroom or lecture hall, on the tram or subway, on the train – from anywhere, you can join us on this artistic-scientific journey into our future and get involved. Whenever you want, for as long as you want!” https://ars.electronica.art/homedelivery/en/

“It’s about trying things that haven’t been tried before, to be an example from which others can learn. The Ars Electronica Festival sees itself as an expedition ship that takes us on a journey into the contradictions of our time. It’s more than just a stage for coming together; it becomes a sandbox for testing different fields of action and breaking down previous thought structures.” (Gerd Stocker, https://ars.electronica.art/aeblog/en/2022/05/27/its-about-trying-out-things/).

[4] THISISSHORT.COM is a joint platform of the four short film festivals Go Short (NL), International Short Film Festival Oberhausen (DE), Vienna Shorts (AT) and Short Waves Festival (PL).

[5] “Eyes Wide Open Online Award” on Sooner

[6] “Reinventing a Festival – The GIFF in Mexico as a Physical, Digital and Virtual Event” (https://www.shortfilm.de/en/neuerfindung-eines-festivals-das-giff-in-mexico-fand-physisch-digital-und-virtuell-statt/).

[7] “Weitere Festivals eröffnen VoD-Plattformen für Streamings unabhängig vom Festivaltermin”

[8] df Satelliten https://www.duisburger-filmwoche.de/festival20/satelliten-information.html

[9] https://www.kasselerdokfest.de/365-tage-kasseler-dokfest

[10] https://www.dokfest-muenchen.de/DOKaroundtheclock

[11] Film festival funding criteria, Austrian Federal Ministry of Arts, Culture, Civil Service and Sport, Oktober 2021

[12] No rule is without an exception: In Frankfurt, the Department of Culture commissioned a feasibility study for a film festival centre, fearing that in future there might not be enough cinemas to accommodate the approximately 20 festivals in the city.

[13] Quoted from: The Film Festival as an Industry Node, Dina Iordanova, University of St. Andrews, 2015.