The old Éclaire works in Epinais-sûr Seine are given a new life with the use by l’Abominable © photo Nora Molitor

It is a world of its own, the world of the film labs – especially when referring to the artist-run or self-governing film labs and not the industrial or commercial kind. This fundamental distinction is no longer self-evident today and despite all the differences within the labs run by artists, this fundamental distinction is nevertheless essential. The basic idea of why people come together, to make a film or to sell a service, influences the approach. Traditionally, a contradiction existed between the processing plant and film artists or producers, as Matthias Georgi put it in his article on the history of the Geyer Works in Berlin, “The amalgamation of theatrical film business with its artistic or even just bohemian level is strictly industrial and technical creativity in film production is extremely detrimental.”[1] Today, at a time when the industrial production of analog film has largely been replaced by digital, and meanwhile, analog film and labs are experiencing hype in the (digital) film industry, within the lab world two principles exist that seem to contradict each other: technical knowledge and standards on the one hand, artistic freedom and experimentation on the other.

Creation of film labs

The emergence of film labs is linked to the history of the film industry and processing labs. In the 1960s and 1970s, numerous non-profit initiatives were founded that were more or less managed and run by filmmakers themselves, such as the Filmmaker’s Coop in London, the Collectif Jeune Cinéma in Paris, or the Hamburg Filmmacher Cooperative, and people who wanted to do “other” films and also wanted to show them. Structures then developed that gradually expanded and professionalized the lab’s activities which, at least in Europe are often funded by the city or state (i.e., Arsenal – Institute for Film and Video Art). Cinemas and distributors who work closely with the cooperatives have split off from their original initiatives and founded new ones such as Light Cone in Paris or LUX in London. These labs still bring “other”, artistic-abstract, experimental, structural, and activist short films to the public today, sometimes also creating space for forms of presentation other than cinema such as film in connection with body, performance art, and also cinematic installations. If only because of the far-reaching changes that digital film and cinema have brought and are still bringing to the field, professionalized institutions still partially evaluate and archive analog cinematic works, but the production of analog or photochemical films today takes place primarily in the labs. Only a few young filmmakers and film artists still develop their work by hand outside of the labs, such as Kim Ekberg, whose film 2GETHER was screened in June 2022 in the competition of the Hamburg International Short Film Festival.

Film poster TOGETHER (Kim Ekberg) © photo Nora Molitor

Believe the Hype…

Although some of the world’s most famous film enthusiasts take up the cause of saving analog film, such as Martin Scorsese, Tom Tykwer, and Tom Cruise who insists on being photographed on 35mm, in the film industry today, nostalgic digital references to analog are more common than real work with analog footage. Since the 1990s, however, more and more labs have emerged that take over the post-production equipment from former industrial labs, university film departments, third parties, and other institutions that discard their machines due to digitization and/or lack of space. Manual development tools in the photo and film labs have been and are being expanded to include viewing, editing, and animation tables, projectors, and sometimes also developing machines and cameras. Hamburger Analogfilmwerke was founded in 2016 specifically to “rescue” a specific device, namely the Arribloc 400 film processor, from a university that had discarded it.

Installation in the Open Space of the International Short Film Festival Hamburg / artist collective Lab Laba Laba (Indonesia) © photo Nora Molitor

Clubs, companies, and collectives are springing up all over the world, creating a scene that maintains the production of photochemical film, as well as networks that exchange and support one another across cultural and language borders. The supporters and members of the labs no longer consist exclusively of people who grew up with analog technology themselves, there are more and more enthusiastic millennials, and workshops with children are also arousing great interest. The main difficulties of the niche that has formed around the production and distribution of “other” analog film are, on the one hand, the (almost) exclusively industrially produced film material, and finding those with expertise in the specifics of different materials and devices.

The equipment and thus the focus of some labs – like the artistic practice of individual artists – also depends on the specific material that is used at a specific time or for a specific purpose. A rough distinction is that of the film formats or image size. While 35mm film was standard in cinemas in Europe up to the 2000s, 70mm film was then and is still particularly expensive and rare. Super 8 was of interest to amateurs at the time, and also 16mm material, which was frequently used for television or in nature reports and is celebrating its 100th anniversary this year, but they actually never had their destination in the cinema. Film material and the cinema come together again and again in the analog film community, but especially 16mm and Super 8 cinema are presented in spatial contexts more adapted to them.[2] Art galleries are showing more and more cinematic works. Festivals and screenings are taking place both in existing spaces and even places that have been developed to show cinematic works from the labs, including those that go beyond a classic film screening. Apart from the Berlinale section Forum Expanded, the Oberhausen Short Film Festival, and the International Film Festival Rotterdam; the Hamburg Short Film Festival 2022 has not only expanded the actual film program with more informal screenings in the “Lampenlager” and archive film presentations but also contains an exhibition in which analog experiments were included. In addition, during the festival, the Analogfilmwerke offered a workshop with Ektachrome Super 8 color reversal film, including manual development.

… read the manual

With the hype around analog in all its forms of representation and the simultaneous lack of specialists – if there ever were any, apart from the authors of the works themselves – sometimes in the context of large exhibitions or festivals, even banal things like the lighting conditions are forgotten and filmmakers or artists would do well not to hide their role as craftsmen, physicists, or alchemists and take over the PROJECTION INSTRUCTIONS[3] directly, and when in doubt, also the projection itself. The film screening becomes a performative act. For example, in the performance THE EYES EMPTY AND THE PUPILS BURNING WITH RAGE AND DESIRE by Luis Macías in which, without any recorded image, sound, or narration, he improvises with two converted 16mm projectors, film material, and emulsion. The latter are repeatedly exposed to heat generated by the projector lamp, and it is not the filmed image but the physical manipulation and chemical reaction of the material that is at the center of the performance. It is actually magical when performed live as it was at the IFFR in 2019 and at the Summer School of the Baltic Analog Lab in August 2022.

Workshop Luis Macías at the BAL Summer School (Cēsis) © Photo Nora Molitor

You can feel the projectionist’s concentration in the stillness of the room, which is broken only by the projector noise, and perhaps also catch the smell of melting acetate film, which unlike celluloid is not self-flammable. Examples of experiments and manipulations with photochemical film material are numerous. They inspired Mika Taanila’s “Film without Film” series in which the filmmaker and curator goes one step further and, among other things, showed numerous works at the International Short Film Festival Oberhausen 2014-2016 that reflect on film as a principle and a medium without a camera and film material, and convert these thoughts into action. Some of these works are also collected on filmlabs.org. The collection is of course not complete, and especially works that go beyond a simple film screening, and use alternative distribution channels, may require more detailed notes for presentation.

collective experiments

The Summer School in Cēsis, was organized by the Baltic analog Lab in August 2022 as a prelude, so to speak, to the EU-funded project SPECTRAL, which over the next four years will organize cooperations with the Oberhausen Short Film Festival and the European Media Arts Festival, as well as residencies, workshops, events, meetings, and research. This is not only being done by the Baltic Analog Lab (Riga) but also by LAIA / Laboratório da Torre (Porto), the Crater Lab (Barcelona), Filmwerkplaats(Rotterdam), Mire (Nantes), and Labor Berlin. The last three have already embarked on a joint adventure in 2014-2016, “Re-inventing the moving image” was about preserving the culture of photochemical film, SPECTRAL is about putting the Expanded Cinematic Arts in the foreground. The aim is not only to pass on knowledge and technology for the production of analog moving images, but also to consider the material, playback devices, and location in their context. The history, but also the possibilities of the analog moving image are still connected to the global and national film industry, despite the initiative of the labs to take something into custody that was neglected by the industry worldwide for many years. There are also public statements and lobbying for analog film by prominent art house representatives, such as the savefilm.org campaign launched by artist Tacita Dean, among others, but manufacturers and service providers continue to only react when it is economically worthwhile, abruptly, and without foresight of the long-term demand. It is also about the production of film material itself, which, even if there are few other companies, is almost completely under the monopoly of Kodak. And despite all the love for analog film and presentation techniques, there are also limits in the DIY labs. The production of emulsion or unexposed raw film, to which Esther Urlus from Filmwerkplaats devoted some time and trials, was largely stopped again. In Cēsis it was possible to discuss whether it might be worth writing to Kodak (or other manufacturers) as a consortium to get the film material at more affordable prices or even a recipe for emulsions. The repair and (re)construction of contact copiers, projectors, cameras, and the 3D printing of spirals were also discussed. Joint decisions on some steps usually take a little longer in context. However, the Summer School was not only used for theoretical exchange. Some attempted and successful experiments were carried out on-site. Similar to the Film Farm tradition,[4] the meeting did not take place in the big city but in a large manor house with a park in the country where a total of almost 50 participants from the global lab scene came together for a week. The attempts were by no means made only by members of the artist-run labs, but also by curators, archivists, artists, and scientists from other disciplines.

Workshop Juan David Gonzáles Monroy, Shutter-Installation © photo Nora Molitor

The results included a 16mm film projector converted into a camera, shutter installations that made moving images out of the landscape, phytograms (16mm film developed with plants), slide projections, and field recordings. In between, there were also lectures, project discussions, and demonstrations of works that were made outside of the Summer School, as well as getting to know each other intensively through practical work. Apart from the European labs, artists from the U.S.A., Canada, Mexico, and India were on-site. It quickly became clear that sometimes “nerdy” individual experiments lead to important discoveries – and there are now a number of websites and wikis through which the film lab world exchanges information – and that physical meetings and joint tinkering is essential.

Learning from each other – organizational paths and forms

Arne Hector founded Cinéma Copains with Minze Tummescheidt and was also involved with LaborBerlin right from the start. In the analog world, you cannot do without analog contact, especially since the labs are often organized as collectives, the type of organization is an essential part of them. How to manage the sharing of tools and responsibilities in spaces that are as free from hierarchies as can be possible is seen in the first part of IN ARBEIT, where exchange and learning from one another with Nicholas Rey, or rather L’Abominable, is shown in film form. While the founding of the French “role model” goes back to the 70s and the lab L’Abominable has officially existed since 1996, the lab initiative of some filmmakers in Berlin dates back to 2010. Most founders are no longer active there. Both labs have now moved several times and, somewhat differently than in Germany, instructions for operating some machines have already passed through several generations in Paris. Lately, L’Abominable has signed a leasehold agreement with the city of Épinay-sur-Seine for the site it operates, le Navire Argo, just over an hour from “downtown” Paris, for a large complex of buildings to take over the former Éclair works. Relocation and renovation are still pending. Although the lab had previously had very large rooms in a former school canteen in Aubervilliers, in which there was also space for developing machines and even its own cinema was installed, the new location is historic because a self-governing, non-commercial lab is moving to the premises of a former industrial film lab. With state and local support, the crowdfunding campaign for renovation and relocation is ongoing.

Lab meeting at the BAL Summer School (Cēsis) © Photo Nora Molitor

After learning with and from L’Abominable, Cinéma Copains worked not only in Berlin but also in Brazil with Luciana Mazeto and Vinicius Lopes, which resulted in the joint 16mm film URBAN SOLUTIONS that is currently touring through the festivals. In some places, collective labs have only been stimulated through visits by members of labs from other cities. The latest wave has in almost all cases, emerged from the initiative of older generations of analog film artists.

Nevertheless, international workshops and co-productions are rather rare and are even more rarely funded, mostly they depend on individual engagement. They have suffered from the lockdowns and especially the travel restrictions, but can sometimes be reactivated very quickly and, above all, unbureaucratically. The Summer School in Cēsis also proved this very impressively. Apart from the European labs and guests from the USA, Canada, Brazil, Argentina, and Mexico, Karan Talwar, co-founder of Harkat Studios was also present. As “Studio” suggests, Karan and his colleagues have taken over a profit-oriented film production company in Mumbai, and they continue to serve orders from the Bollywood and advertising industries. Based on the production, the collective can not only afford its own independent venue, where they have been hosting a 16mm film festival since 2017, but it can also provide space for other non-commercial initiatives and maintain an association with which they hold analog workshops and a joint engagement in experimental film practice. Unlike most European labs, Harkat does not receive any public support. Apart from old projectors, editing tables, and development machines, they also found old rolls of film in the rooms they took over that are often processed into found footage films with subversive comments on state content, or at least content prevalent in commercial films, narrative patterns, or social clichés, such as in their film 16MM SELFIE. Analog films are created radically independently and “by hand” by individual artists, and they often have aesthetic elements in common that arise from the devices and techniques used. A common film language is discussed in the group that sometimes affects the selection and work of the filmmakers and artists, who now study and work at Harkat in residency programs for longer periods of time. Karan Talwar says in the beginning, they knew nothing about the international lab world, which actually only came about through cooperation with LaborBerlin, Kodak, and the Goethe Institute. This opened up a growing exchange with European structures for Harkat in analog experimental film or expanded cinema.

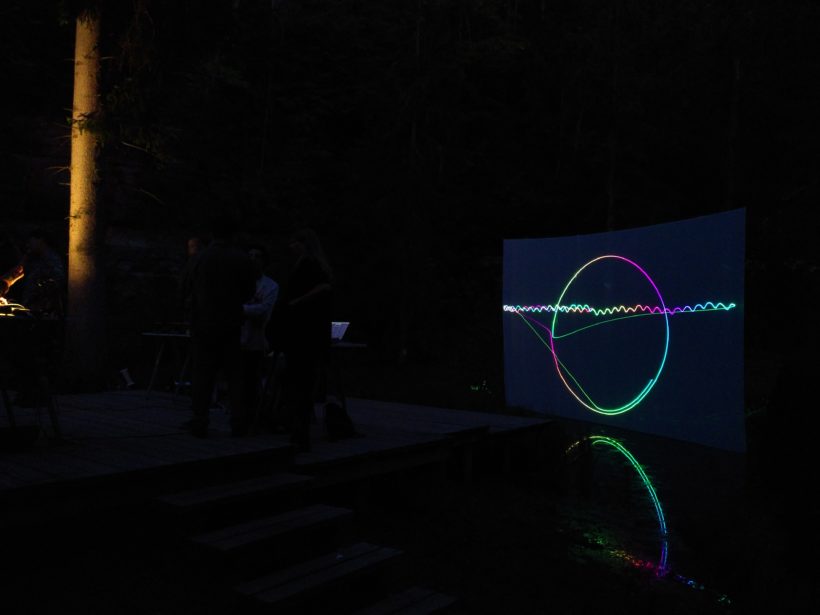

Through Bernd Lützeler, who is a member of LaborBerlin, old snippets of Bollywood productions also come to Europe and the rest of the world. There has been cooperation between him and members of Harkat for years. Harkat means something like action/movement/deed. His film HOW TO BUILD A HOUSE OUT OF WRECKAGE AND RAGS not only refers to Holly- and Bollywood but also questions the found footage approach of creating new meaning from the compilation of more or less found material or even rewriting film history. Ojoboca (Anja Dornieden and Juan David Gonzales Monroy) go a step further here: in their films and performances they treat (allegedly) found material and stories as their own and vice versa. In order to understand their work, or at least some of their work, which is not necessarily a prerequisite for liking it, it helps if you know something about the lab world and like to deal with physical, philosophical, or film-historical questions that also do not leave out cinema-era techniques. They often work together with members of other labs or archives, and most recently with Andrew Kim in the film INSTANT LIFE, which is also currently touring through festivals and that, strictly speaking, only makes sense with the introductory story, the preface, explaining why it contains performative elements. Some members of Mire are experimenting with this in a very different way. At the Summer School in Cēsis, the participants, despite the late hour, were able to see Aurélie Percevault’s performance in which she used a 16mm projector. Moving images projected into self-made clouds of fire and smoke provoked not only a 3D effect but also ghostly apparitions. Also admirable was how the clouds of smoke got lost in Bernhard Rasinger’s laser installation about 20 meters away in which a mobile screen, in the form of smoke before it dissolved, beautifully combined analog recordings with the most modern lighting technology.

Abschlussabend / Laserinstallation BAL Summer School (Cēsis) © Foto Nora Molitor

Hope remains that analog tools will not only be shared through the lab world – but if they really do become obsolete – that they will also be exchanged for new ones. Further experiments and what comes out of them will be seen in the numerous activities of SPECTRAL in the next few years. Despite all the digital overlaps and challenges that even a world attached to the analog does not avoid, nevertheless: See you in the reel world.

[1] Karl Geyers Werk in: Film-Kurier 15.07.1920. quoted in: Matthias Georgi: 100 Jahre für den Film – CinePostproduction 1911-2011: vom Kopierwerk zum digitalen Dienstleister. August-Dreesbach-Verlag München 2011. ISBN 978-3-940061-60-7

[2] In Europe, mostly in publicly funded municipal cinemas or as part of non-profit initiatives such as Kino Climates, A Wall is a Screen, or festivals such as the Dresdner schmalfilmtage.

[3] A film by Morgan Fisher, 1976, USA, 16mm, b/w, sound, 4 min.

[4] Independent Imaging Retreat, started in Canada in 1994 by Phil Hoffman providing instruction in manual film processing.