VoD offerings by film festivals – screenshot collage of clips from the Eventive platform

Film festivals generally serve two main functions. They showcase new films in a festive setting and facilitate encounters between the industry and the audience. Under pandemic conditions, neither is possible in real space in a physical location. In the first part of this article, I described and analysed alternative online formats for the meetings and discussions that normally take place at festivals. This second part is devoted to the streaming solutions that replace screenings in the cinema.

I would like to point out first of all that this analysis focuses on the short film sector, which has some special features that are not comparable to other forms of films and festivals. The main difference lies in the economic environment. To the extent that one can speak of a market at all in the case of short film, it consists of widely ramified niche markets that are usually located in the intermediary third sector[1], or it is part of other markets, such as the education or art market. In this respect, much of what I describe here applies only to short film.

Hello World!

At the outset of the pandemic, many festival organizers were thrilled with the surging view rates on their websites. One festival even reported more than 1 million “visitors” in April – an otherwise unattainable number. In the initial euphoria, many festivals, whether out of ignorance or calculation, were boasting new records in their web statistics, although this in fact says nothing about the quality of each visit, as total page visits, including those of bots, were counted as unique actual festival viewers.

Unfortunately, not many festivals have to date released statistical data that could really provide us with a detailed picture of the situation. It would be important to know, for example, the number of individual film views and how long they were watched. Lacking such data, I had to rely on indirect measurement methods that reflect only rough trends. These include dwell times on festival pages as determined using SEO tools, showing in most cases between 2 and 5 minutes. However, these are only average values including “drive-by clicks”, while really interesting parameters, such as the view duration per film streaming, remain hidden.

“Filmmakers need to know how many people saw their film, how much of it they watched, and be able to use this data to build a case for their film with distributors, press and other audiences,” says producer and distributor Brian Newman in an IndieWire article[2] about whether filmmakers should take part at all in online festivals.

Visibility – pros and cons

Assuming a functioning film market, the greater visibility offered by online festivals is actually counterproductive. This only applies however to films that have prospects for being sold for TV or VoD. For these films, only a physically unique screening or premiere at a renowned festival would work to their advantage. Widespread streaming by contrast – no matter by whom – is commercially damaging.

The latter may not be true for short films. But there is certainly added value in this case as well that can only be generated by festivals that take place physically. This includes the attention generated for the film and the value of direct feedback from the audience on site[3].

And the buzzword “visibility” also obscures discrepancies between the quantity and quality of the exposure. There is, after all, a difference between delivering a film to a lone viewer as a data stream on a laptop and projecting it for an audience on a big screen at the cinema as part of a public event.

It would also be interesting to find out which types of viewers from which regions are reached by film streaming who would otherwise not attend the actual film festival. Theoretically, anyone on this planet who has an internet connection can access online offerings.

Apart from global inequities[4], paywalls that may be too expensive, or censorship in the respective country, the reach for online films theoretically has no limits. Nevertheless, almost all film festivals and most short film festivals have opted for geoblocking.

Reach – global and/or village?

Nearly all festivals reviewed reported that the number of countries reached was higher than the number normally physically represented by visitors to the festival. This is hardly surprising but would have to be quantified in more detail – including a comparison to online offerings before the pandemic. With the help of server statistics, such evaluations can be made by the festivals themselves – but are difficult for outsiders! A comparison is also complicated as each festival excludes different territories by means of geoblocking.

Online web statistics tools are in the meantime fee-based. What I was able to find out without subscribing to such services is therefore based on free results offered as teasers for a subscription[5], allowing only broad trends to be identified and guesses made.

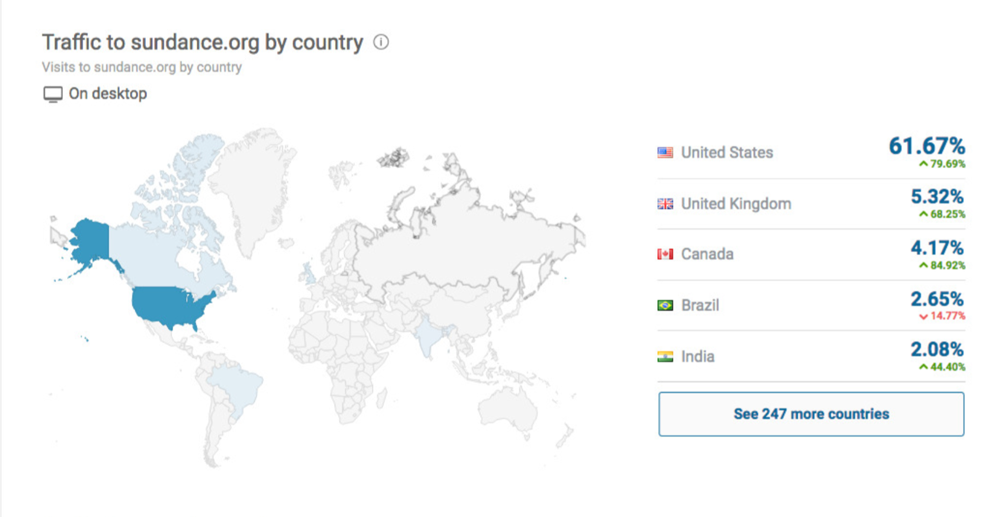

In terms of geographic reach, these glimpses of the statistics reveal that all festivals receive the most page views from their own country. Ten days before the start of the current Sundance Festival, for example, more than 80% of website visitors came from the USA, followed by single-digit shares from other countries. During the festival, the US share dropped to 62% and views from other countries increased.

Sundance “Analytics by country” – screenshot of SimilarWeb

Some festivals have themselves commented on the origin of the users of their online services. Below are some revealing statements on this topic by festivals of various types focusing on a variety of genres:

• CPH:DOX reported, “Previously, 90% of our audience was from the Greater Copenhagen area. That figure is 70% this year, with 30% coming from the rest of the country.”[6]

• According to the International Short Film Festival Oberhausen’s press release, internet users in almost 100 countries watched the festival films online. Festival passes were purchased in around 60 countries and trade visitors from almost 70 countries used the online services. In comparison, physical visitors to the festival in 2019 came from more than 50 countries.

• DOK.fest Munich commented that “at the regular festivals (…) the majority of the audience comes from the greater Munich area. This year, more than half of the visitors were not from Bavaria.”

• The Filmschoolfest Munich (no geoblocking) announced 10,000 international views, though “our regular Munich audience has also remained loyal to the festival”.

• The Filmkunstfest MV in Schwerin reported: “37.14% of the users of #filmkunstzuhause came from Mecklenburg-Vorpommern, almost 20% from Berlin and over 14% from Hamburg. Apart from the big cities, web users from other German states also visited the site, including almost 7% from North Rhine-Westphalia.”

• The Flatpack short film festival (UK, without geoblocking) announced: “Around half of the audience for our physical festival tends to come from Birmingham, but in this case it has been less than a quarter. The proportion of international web hits went from 5% in 2019 to 20% in 2020, with a particularly strong showing for countries like France, Hungary and Japan that had a presence in the programme. 68% of viewers were UK based.”[7]

Festival communities and neighbours from home

It is worth noting that most film festivals have been able to retain their regular audience and that the people who are reached online in addition to that audience have either geographical links (neighbours) or socio-cultural ties (communities) to the respective festival. Whether it’s more one or the other depends on how the festival was physically networked beforehand, and how well it has established itself regionally or internationally.

Festivals whose concept commits them to certain film formats or which are important meeting places for filmmakers and professionals (“industry festivals”) can expand their international reach online but remain dependent on their inner circles (“communities”). I found this subjectively confirmed in the online discussions published by festivals I am familiar with: I recognized the names of most of the commentators.

So-called audience festivals also reach in their online editions predominantly viewers from their geographical surroundings. They benefit here from classic word-of-mouth advertising. The social ties that festival cinemas foster are helpful here.

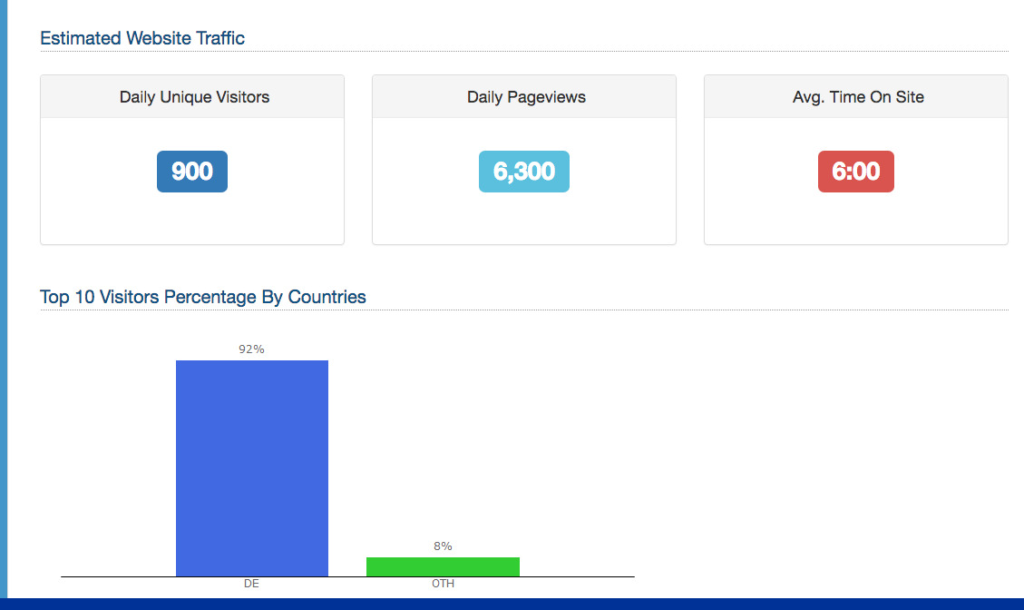

Example: Film festival traffic figures and countries of origin in percent (screenshot of Site Traffic Estimator site)

Summing up, even if the geographical reach of festival programmes can be extended through online streaming, there are many indications that new target groups or other audiences are actually being attracted only on a small scale.

Visibility again: hits vs. clicks

Many short film festivals do not or cannot register actual viewing numbers for individual films. This is especially the case when they put short films online in programme blocks. Few have published data on which films have been viewed and how often. Here are some interesting comments on this topic:

• According to a press release issued by the International Short Film Festival Oberhausen, internet users in almost 100 countries watched the festival films online in 2020. Well over 2,500 festival passes were sold to viewers from around 60 countries. In addition, over 1,000 industry visitors from almost 70 countries took advantage of the festival’s offerings. However, since passes were sold giving users access to the entire festival (€9.99 flat rate), the viewer numbers cannot be directly compared to previous years. The year before, the festival reported 18,200 admissions to programmes, 3,800 of which were so-called purchased tickets. There is no difference between the two years in the number of accredited industry visitors.

• With 75,000 “viewers” counted, DOK.fest Munich has been the most successful of the German festivals online to date (as of 12/2020). The press release did not however state how many people accessed the film programmes. According to my own calculations based on the report on the proportional solidarity payment to cinemas (€19,000) and on ticket sales, I estimate that about 25,000 online tickets were purchased for film programmes.

• Nippon Connection recorded 15,200 “on demand plays” and about 10,000 page views of live programmes (mostly talks and discussions). The year before, 17,000 admissions to on-site events were registered.

• The Filmkunstfest in Schwerin, which considers itself an audience festival, normally has up to 19,000 visitors. In the online edition, the film programmes (including five short-film reels for €4.99 each) were viewed just under 2,500 times.

• The festival interfilm Berlin reported: “Over 18,800 digital cinema seats were filled. That’s almost as many as in a ‘regular’ edition.” (PR 18 December 2020). The festival offered 32 programmes on the VoD platform Sooner for one month at a flat rate of €7.95 (festival pass).

• The Vilnius International Film Festival took stock as follows: “IFF films were streamed 56,000 times. According to data from the research company Kantar, most often two people watched each screening. That adds up to 112,000 total viewers. In comparison, last year’s festival was attended by 126,000 filmgoers. Despite these numbers, we lost over half of our target ticket revenue, which is a significant financial blow (…).”[8]

So in terms of the “visibility” of the films in the programmes, the difference between films streamed online and those shown at the festival cinema is often not as great as page-view figures might suggest. And very locally oriented audience festivals are less likely to succeed in outstripping admissions to physical film screenings with views of their streaming offerings. One must assume, however, that there is often more than one person watching (who neither counts nor pays) behind each click.

It is noteworthy that documentary festivals are more successful online than festivals that mainly show feature films. Perhaps audiences are simply used to watching documentaries on television rather than at the cinema?

It is also conspicuous that, over the course of the pandemic, the popularity of online film festival offerings has declined. This corresponds with the general trend in media use, in which an extreme increase at the beginning of the pandemic was followed by streaming fatigue.[9]

Streaming models

Most short film festivals have opted for an online concept that mimics physical festivals. Competition films are therefore shown online in full-length programmes. This simulation tactic makes sense in that the willingness to pay for individual short films is very low. The potential commercial prospects are however undermined by the many providers who stream (only) short films for free. What’s more, it is unrealistic to ask home audiences to pay for films they have never heard of.

In fact, festival payment models for individual films always put unknown filmmakers at a disadvantage, and not only in the short film sector. As a rule, only films advertised in the media or films by and with big names have really high ratings.

The simulation of physical festivals also includes geographical and temporal restrictions. Nearly all short film festivals have opted for geoblocking, although there are not really any sensible economic arguments speaking for territorial restrictions in the short film sector. The restrictions are made more for reasons of festival policy. In an ideal world, short-film makers would not have to fear that they would be denied access elsewhere because of constraints on international availability and the demand that festival submissions be premieres.

Nevertheless, this example shows what a complicated situation arises when traditional concepts from one cultural practice (cinema, festivals) get mixed up with the characteristics and expectations of another cultural technology (ubiquitous internet access). There is no such thing as an accessible place on the internet (in the cloud ;-), just as there is no such thing as a “premiere” there if what is meant is a unique event taking place at a specific time in a specific place.

The simulation of the cinema theatre with its limited number of seats (space) per screening (time) by artificially limiting online streaming would seem paradoxical. The world of the internet, perceived as a metaverse, is after all limited only by bandwidth and storage capacity. In the simulation, on the other hand, a festival visitor buys a virtual ticket to his or her own home, where only a few people can sit on the sofa to watch a film online.

The most important advantage of distributing films on the internet, namely anywhere, anytime access, is thus nullified. For filmmakers, the only benefit of artificially limiting access is that the door to festivals that demand premieres is then not closed to them. Insofar as they can never be sure whether they will be selected and accepted “elsewhere”, this form of speculation ultimately puts them at risk of forfeiting greater visibility for their films.

From the perspective of the festivals as well, such limitation would at first seem anachronistic at least in economic terms, because they are missing out on potential view fees. On the other hand, these restrictions (still?) seem to be working. VoD providers that artificially limit views, such as Festival Scope and MuBi, among others, confirm that this is so.[10] The success of the strategy can probably only be explained in terms of behavioural psychology, for example with the FOMO phenomenon (fear of missing out) or with a compulsive sense of “urgency”.

Is VoD a viable option for the future?

In 2019, “streaming wars” was the buzzword of the year in the VoD industry. It refers to the competition between online and cable as well as with IT and media companies that are newcomers to the market (e.g. Disney). Against expectations, all of them saw growth in 2020, but only because of the pandemic. Market analysts[11] predict the end of growth and a market shakeout as early as 2021. The buzzword of the future, they predict, will be “streaming fatigue”!

In Europe alone, there are already more than 300 VoD providers. The independents and quality labels among them are struggling to get out of the red – despite EU subsidies[12]. Unlike “good old” analogue technology, VoD requires many more production and delivery steps than a film lab, a distribution office, a film warehouse and a cinema. The intermediate steps required to offer films of adequate quality[13] online to a larger audience include, in short: a digital master, conversions for different end-device formats, storage and provision of data by the data centre of an Internet Service Provider (ISP), and distribution of the files via a Content Delivery Network (CDN)[14], possibly with a global presence but with regional data centres close to the end users. In order to make all this possible, software is needed for web programming, rights management (DRM), a client management programme, a payment system and so on. All of these are significant cost factors.

In Europe alone, there are already more than 300 VoD providers. The independents and quality labels among them are struggling to get out of the red – despite EU subsidies[12]. Unlike “good old” analogue technology, VoD requires many more production and delivery steps than a film lab, a distribution office, a film warehouse and a cinema. The intermediate steps required to offer films of adequate quality[13] online to a larger audience include, in short: a digital master, conversions for different end-device formats, storage and provision of data by the data centre of an Internet Service Provider (ISP), and distribution of the files via a Content Delivery Network (CDN)[14], possibly with a global presence but with regional data centres close to the end users. In order to make all this possible, software is needed for web programming, rights management (DRM), a client management programme, a payment system and so on. All of these are significant cost factors.

Whether a film festival can succeed in gaining a foothold with online film offerings in this technical and economic environment – we might call it a shark tank – remains to be seen. The price wars have already begun …

“Sign up for a new annual subscription by 30 June and save 40%!”

“Unlimited streaming of over 2000 films from our catalogue for 6€ per month”

“Immerse yourself in a bath of documentaries”

“Hurry now before this offer expires!”

“It’s a tsunami of online screenings, masterclasses and free yoga classes all around you! This needs to be addressed. While the importance of an online presence is greater than ever, it’s also harder than ever to stand out, to even get that chance to reach an audience.” This is how Asia Dér and Sári Haragonics describe the situation from their point of view as documentary filmmakers.[15]

Networks are currently being established[16] that may stand a chance of mastering this challenge. And yet it is certainly telling that joint projects between festivals that have already been around for some time, such as the Doc Alliance’s dafilms.com platform, are struggling.

Film festivals have other interests than just distributing films. Their status also depends on the internationality, number and quality of their guests. And public sponsors also appreciate their impact on the local economy. Festivals create financial and ideological incentives through audience building. This ranges from free accreditations, to invitations including travel expenses, to fees paid to curators, workshop leaders, lecturers, etc.

A considerable portion of these costs could be saved by forgoing personal participation – perhaps even increasing the festival’s global profile in the process.

If taken to its logical conclusion, however, this strategy would entail a thorough change in the core business of festivals, transforming them into a kind of alternative Amazon Prime. The cultural loss would be very painful, just like the supplanting of cinemas by streaming platforms that is already being predicted by some.

Hardly any festival will set out to completely reorganize itself, but almost all of them have announced that they will be taking a two-track approach in future, i.e. that they want to put on “hybrid” events. Viable concepts for such a dual strategy have yet to be developed. In particular, it is not possible to foresee what consequences a stronger online presence might have for the actual live event. The absence of international guests? Reducing the on-site audience by half?

Online reach does not equal distribution, and distribution does not equal exploitation. Even in the hybrid model, significant fees are hardly likely for the filmmakers. Ultimately, the pros and cons of online participation must be weighed on a case-by-case basis. Film by film and festival by festival. Only one thing is for sure: personal encounters, the experience of hospitality and conviviality cannot be replaced by telecommunications and must therefore have a place in the true sense of the word.

Link to Part 1: Film Festival Corona Strategies – A Critical Look at Techniques and Formats

Film Festival Corona Strategies – A Critical Look at Techniques and Formats (Part One)

Footnotes:

[1] “The third sector is characterized by a mix of the regulatory mechanisms prevention, support, contract and solidarity. Organizations in the third sector are distinguished by their economic, political and socially integrative functions.” (Gabler Wirtschaftslexikon)

[2] https://www.indiewire.com/2020/05/filmmakers-questions-virtual-film-festivals-1202229623/

[3] See also our online article “Online Please Not Forever! Some Filmmakers’ Experiences”

[4] According to the latest study conducted by We Are Social, the “Digital 2020 Report”, 40% of the world’s total population remains unconnected to the internet (31% of the total in Southern Asia and 27% in Africa). In many countries there is additionally a gender gap. See also: https://datareportal.com/reports/digital-2020-global-digital-overview

[5] A note on indirect research using free analysis tools: Most providers, such as Alexa, only provide sample data, in other words, only the first few results are shown. Through detours and comparisons, at least some clues can be extrapolated, particularly when larger festivals are analysed. The Audience Geography list is likewise capped after three countries. And unfortunately only data from very large websites with a lot of traffic is read out. In Europe, even Rotterdam is not “big enough”, let alone any of the short film festivals.

[6] Tine Fischer in an interview: “How CPH:DOX survived its biggest crisis”, www.dfi.dk, 24 April 2020

[7] https://www.independentcinemaoffice.org.uk/blog-how-flatpack-took-their-festival-online-during-the-coronavirus-crisis/

[8] Press release 10 April 2020

[9] See also our article: “Too much content – studies show how #stayathome influences media usage“

[10] See our article: “Short film festivals and video-on-demand Part 2: Collaborations with VoD providers”

[11] For example Maria Rua Aguete in the article “The Streaming Wars Could Finally End in 2021”: “For Netflix and Amazon, 2021 will be their smallest year of growth in absolute terms since 2015 (…) the battle may be over. It will just be a matter of which is left streaming.” (Wired, 14 December 2020, https://www.wired.com/story/disney-plus-hbo-max-streaming-wars/)

or: “Brutally Honest Insights on a Wild Year in the Streaming Wars” (Variety, 30 December 2020, https://variety.com/2020/digital/news/streaming-wars-2020-netflix-disney-plus-hbo-max-1234876686/)

[12] In a panel discussion on VoD in Oberhausen, Anaïs Lebrun reported that MuBi would finally make it into the black that year (2019)

[13] A distinction is made between the measurable Quality of Service (QoS) and the more subjective Quality of Experience (QoE). QoS deals, among other things, with questions of reliability and speed of transport, sound and picture quality, and automatic adaptation to the capabilities and dimensions of the different end devices (from mobile phones to XXL mega TV screens). QoE, one might say, refers to ease of use for the viewer. In other words, questions of manageability, design, navigation, search and information functions, handling (e.g. payment), and controllability during playback (e.g. pause, fast forward and rewind).

[14] The main suppliers of this technical infrastructure are: telecommunications service providers (in Germany, for example, Telekom and 1&1); data service providers, some of which also offer CDN services (e.g. Amazon Web Services, Rackspace); and/or stand-alone CDNs such as Akamei, ChinaCache, CDNetworks, EdgeCast Networks and Wangsu. In between there are technology providers for CDNs such as Adobe, Azur and Cisco.

[15] Source: survey by Filmmaker magazine during the festival Hot Docs: https://filmmakermagazine.com/109738-hot-docs-2020-doc-makers-discuss-the-digital-edition

[16] See our articles: “Doc Around Europe und andere neue europäische Festivalnetzwerke” https://www.shortfilm.de/doc-around-europe-und-andere-neue-europaeische-festivalnetzwerke/ (in Germany only)

“Vier Kurzfilmfestivals haben VoD-Plattform gegründet”: https://www.shortfilm.de/vier-kurzfilmfestivals-haben-vod-plattform-gegruendet/ (in Germany only).

“Online Aggregators Boom During Pandemic Crisis at Festivals”

1 Trackback