Pitfalls, tricks and glitches in video conferencing (with zoom bombing;-), meme by rww © CC BY-ND

Since the start of the pandemic, film festivals have admirably sought out and found alternatives in terms of what they offer their audiences, even in the face of losing their screening and event locations.

In part one of this article, I am discussing and analysing online formats that have been chosen to replace physical encounters for talks and discussions. Part two, which will be published later, focuses on online solutions to replace cinema projections.

The basis for this article consists of records of website visits and publications by the festivals. Taking a random-sample approach, to date I have ‘visited’ just under 90 short film festivals and festivals with short films in their competition programmes. Most of the data – amounting to about 1,000 screenshots and documents – comes from the period at the start of the pandemic.

The Initial Situation: Online Facilities Prior to the Pandemic

Almost all festivals had already gained some experience prior to their first online edition, and they were able to build upon this. This consisted of social media usages, as well as applications for the event management and the film selection viewing. These areas were expanded to become the new pillars supporting this non-physical (online) presence. The former as platforms for discursive formats and the latter as distributors for streaming formats. In this way, it was expected that the essential features of a film festival – the encounters, discussions and talks among the attendees on the one hand and the film selection viewings and cinema projections to audiences on the other hand – could be ‘translated’ into a digital context.

In the past, social media platforms were used by film festivals to a more half-hearted extent as they maintained quite a distance to them mentally speaking. And as a rule, the festivals’ PR and press sections were responsible for this. But with the pandemic, they were suddenly accorded a central role in the activities, because they held the promise of being able to rescue the interpersonal sociability aspects and conversation culture of the festivals to some extent. The question then arises of whether this could succeed – and how. I have structured the presentation ‘down-to-top’, ranging from less complex to more complex applications and formats intended as options for festivals.

In order not to fall into the ‘trap’ of understanding the mainstream platforms that currently exist and are used overwhelmingly by festivals as a natural extending, so to speak, of the physical activities into digital networks, I will try to present and critically question this on the basis of concrete examples and implementations that struck me when browsing festival websites. So as to be able to understand and convey better the inner logic of what is offered digitally, together with the cultural tools and technologies, I shall also cast an eye on their media-historical genesis.

Option 1: Virtual Communities – Facebook & Co

Brickfilmfestival, online festival party with traditional rhubarb pie on Discord, screenshot dated 13.06.2020Brickfilmfestival, online festival party with traditional rhubarb pie on Discord, screenshot dated 13.06.2020

In the early days of the internet, so-called bulletin board systems (BBS) arose as discussion forums. The Well[1] in California’s Bay Area was one of the best-known ones. Already back in 1993, Howard Rheingold described The Well in hopeful terms as a model for democratically organised ‘virtual communities’: »social aggregations that emerge from the Net when enough people carry on those public discussions long enough, with sufficient human feeling, to form webs of personal relationships in cyberspace”[2].

Such a platform intended for an open discourse that enables and facilitates global networking would be ideal for the situation in which we find ourselves today. One notable and highly interesting aspect, which cannot be presented in detail here, is that according to Rheingold, The Well only worked for people who lived in the same region (Bay Area).

However, the cyber pioneer’s visions already foundered a decade ago in the face of economic reality [3].

Platforms like Facebook or messenger services such as WhatsApp constitute the commercial successors of this idea. But unfortunately, any discourse and networking there act and serve merely as showpieces and promises. In the backend, it is all about user data and not about the content. For the algorithm, a click is enough to record what is essential for the business aim, namely the ‘likes’ accorded to a product or a lifestyle. The users have adapted themselves to this and developed a specific communications culture. With it all merely being about expressing an opinion, rather than entering into a dialogue. The comments by users about film talks and festival discussions then also match this level, such as »Super, impressive!« (…) »Hello world«(…) »Congrats!« (…) »Wow!«. We can also do without such monosyllabic reactions and responses, which is by the way the case on platforms that cultivate a distinguished style. Video conference playbacks on Vimeo, for instance, generate almost no comments.

Conclusion: Such platforms do indeed have the advantage of providing cost-free space for the posting of pre-recorded talks and discussions. Yet for that, the ‘visitor’ comments are monodirectional interjections, and not offers to have talks or discussions. For which reason, they are unsuitable for communications in the sense of the conversation and discussion practices found at film festivals. And as feedback from the audiences for the filmmakers, this format is almost worthless.

Digression: 25 Years of Video Conferences and Virtual Film Festivals

In 1994, the first “QuickCam” for computers came on the market. In 1995, researchers at Cornell University commercially launched the CU-SeeMe video conferencing software, which was initially utilised on a professional basis by ABC News. Parallel to this, Apple developed its QuickTime Conferencing (15 B/sec, 320p, b/w).

VFF webcasting from laptops in Oberhausen © private QuickPict images from Peter Wintonick

That same year, Pierre Bongiovanni and Cherise Fong from the CICV Centre Pierre Schaeffer (Montbéliard, France) issued an invitation to Le Festival OLE (On-LinE) »to test how we can use the internet for the exchange and the distribution of digital artworks [4]«. In 1996, the iLine Group (which emerged from Indiewire) streamed the opening gala at the Sundance Festival. The group belonged to the Canadian documentary filmmaker Peter Wintonick (Manufacturing Consent: Noam Chomsky and the Media). Wintonick founded the Virtual FilmFestival. »VFF (…) hosts realtime press conferences with directors and other film notables from film events around the globe.[5]« The VFF broadcasted on a daily basis from the next Sundance Festival. In Europe, the Berlinale used the system from 1996, and was then followed by the International Short Festival Oberhausen (curated by the author of this article).

Option 2: Digitalised Video Telephony [6]. – Videochats

The current methods of choice for conducting talks and discussions over longer distances consist of videochats and video-conferencing applications. Both live transmissions as well as time-shifted playbacks (with or without editing or processing) of recordings are possible. And many festivals were already uploading such recordings online even prior to the pandemic. The increase in call-ups or accesses online has, however, remained low during the pandemic.

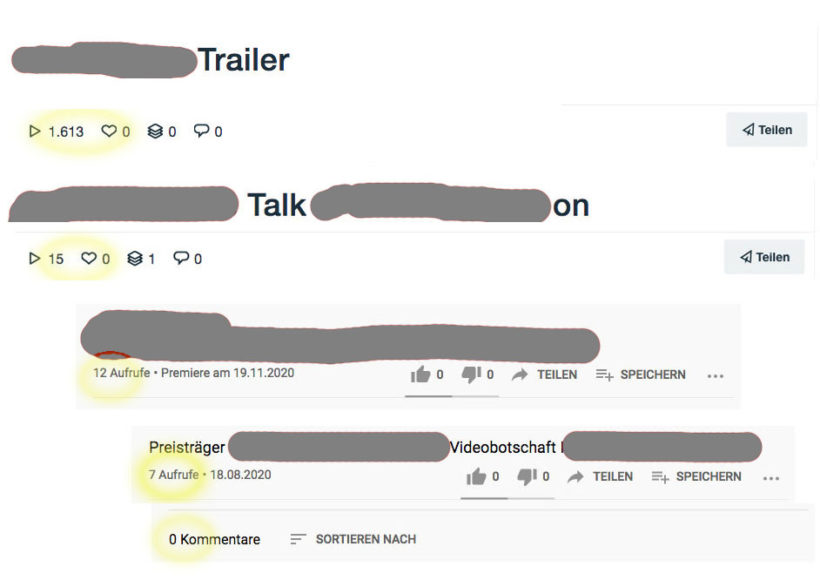

Example: Participant figures, views on Vimeo and YouTube (anonymized)

With the exception of masterclasses and practical workshops that are called up or viewed online clearly more often, the number of accesses to the discursive options offered are mostly only in a double-digit range. At quite a lot of the discussions and talks broadcast live in which I myself ‘participated’, I found myself alone with two or three other persons. I suspect that there are technical reasons for the low interest, but also deficiencies on a conceptual level.

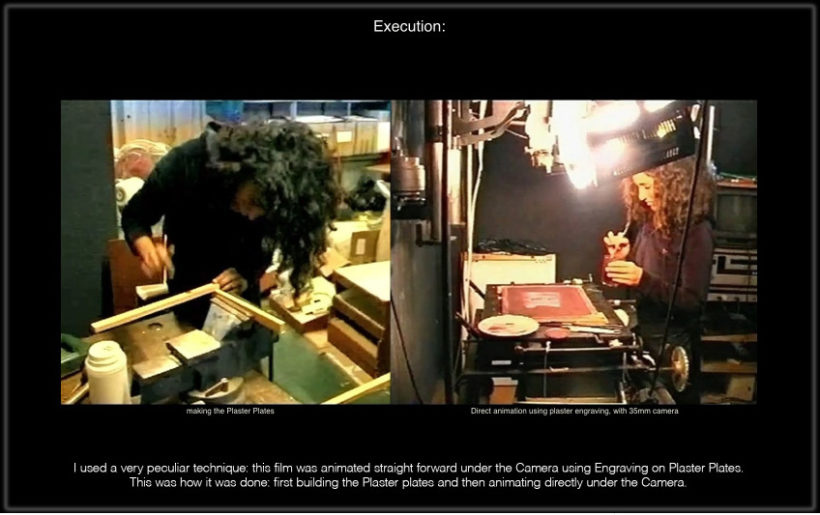

That online presentations which are well thought-out conceptually can be convincing is revealed by Regina Pessoa in her contribution “My Creative Process”, which interfilm Berlin posted for a masterclass with the filmmaker.

(see image with link, cmd <view image> enlarges the presentation in the same window)

The first technical shortcoming consists of the fact that it is impossible to work professionally with standard consumer equipment, tools and applications. The low-quality cameras mostly have only millimetre-sized optics that also cannot be set or adjusted (colour temperatures, focal lengths. etc.). The in-built microphones record background noise from their surroundings and the loudspeakers cause echoes. Likewise, there is often a lack of bandwidth and stability in terms of the network transmissions. With the results being artefacts, asynchronisms, packet losses and major latencies.

Now while this may not be a tragedy during a private Skype call to your granny or favourite uncle – for a broadcast potentially being disseminated to the public worldwide it certainly is so, in my opinion. And that especially when such a broadcast should serve and function as the presentation and self-presentation route for filmmakers and film festivals.

There is no further need here for me to present the numerous fails, occasional oddities and just plain awkwardness to be found at times in online festival discussions, as it is reasonable to assume that by now everyone involved have themselves probably been the cause of them, or at least seen them. During physical encounters, the cultural skills of communications learned over the millennia support us. The body postures, gestures, looks and much more signalise important information to us. But for that, the willingness to talk and communicate, our agreement or rejection, disinterest or exhaustion, and indeed our personal mood that moment, become ‘lost in transmission’. We only have to think about how during a meeting we can agree spontaneously to a short break without having to talk much about this or even hold a vote with raised hands.

The second source of errors and faults consists of ‘shoots’ without any recording assistance, such as visual direction, lighting, camera operation or sound recording. All of this is left to the computer – like with surveillance cameras. Or the visual editing gets transferred beyond our control to the algorithm of the conferencing software, with the audio level determining which image will be placed in the foreground or moved to the sidebar.

Conclusion: Using the modest technological conditions that also permit everyone to become their own selfie director, quality inevitably suffers. Yet some of the related faults and deficiencies would be avoidable (please see suggestions for improvements below).

I found some positive approaches to avoiding faults and deficiencies at DOK.fest Munich. At its video conferences, in addition to the moderation, they apparently also had a director who was mostly included in the shot at the start of the talk or discussion – which I also found to be pleasant. (please see image)

Film discussion on Vimeo, DOK.fest Munich studio (left above), director Lina Maria Mannheimer (left below) and team at home, screenshot 09.05.20

Perhaps the fact that the DOK.fest Munich’s online presence is counted among the most successful to date under the German festivals has contributed to this.

The Danish CPH:Dox festival also enjoyed high viewer ratings, even though the organisers only had a few days to relocate it online. The highest viewer numbers I have been able to record to date for a live videochat occurred during a talk with Edward Snowdon: More than 2,000 people watched the talk simultaneously. But of course, this is not really a fair comparison considering the individual involved and other circumstances – as it was clear from the start that Snowdon could only participate by video link.

Option 3: Television – IP-TV

Recordings of talks and discussions that had been properly prepared and reedited, rather than assumed unchanged from live videochats, were received more favourably by the viewers and filmmakers involved[7]. In any case, the streaming of talks and discussions that can be staged and post-produced represents a good option. Which is basically television, or more correctly IP-TV – the distribution of broadcasts by internet protocol via data networks.

At the International Short Film Festival Oberhausen, the talks with filmmakers – embedded in a TV programme style but not uniformly post-produced – were edited in between the films in the competition programmes streamed in blocks.

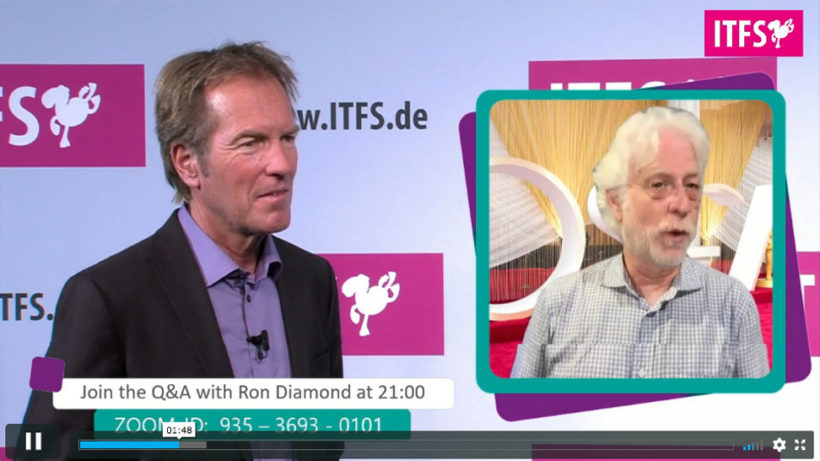

Live broadcast of the Stuttgart International Festival of Animated Film on Vimeo, screenshot dated 06.05.20

Live television formats tend to be applied more rarely. The Stuttgart International Festival of Animated Film was the first one to ‘jump in at the deep end’ with this approach, but they did cover their backs by engaging a television presenter. (Image)

Possibly I may have overlooked other live broadcasts. As a viewer, you cannot clearly recognise anyway if, for instance, a choreographed or staged festival opening is being broadcast live or from the box.

Although they correspond to the old linear television prior to the invention of the video recorder, IP-TV formats are still more suited for conveying festival atmospheres than are the interactive chat-and-click participation formats.

Conclusion: IP-TV has broadcast one to many and there is also no feedback channel available for audience participation or ‘virtual encounters’.

IP-TV means that no attempt is made in the first place to imitate or replicate online a festival with its talks, discussions and encounters.

The understandable attitude of many film festivals to act as though their festival really had been held not only caused the breakdowns and faults mentioned above, but is also perplexing because it intrinsically contradicts the reception and the media usage experience of the ‘festival visitors’, of whom not all are actually “digital naives”. The naive attitude of some festival organisers also found expression in occasional linguistic gaffes by their PR sections. Sentences that we often heard, such as “bring the festival event to your sofa “, “festival programme conveniently at home”, or “raise a toast to the award-winners with a glass of good wine”, are pure blarney.

Option 4: Immersion – Virtual Environments

Even if some organisers talk about virtual meetings or festivals (a further naive misunderstanding): Two-dimensional screen applications are not virtual environments. True virtual environments, such as computer-generated 3D constructions, have not yet been discovered by festivals as an option for encounters. To my knowledge, with there being only one exception which I have already presented in the article entitled: Reinventing a Festival – The GIFF in Mexico as a Physical, Digital and Virtual Event.

I would suspect that the main reason for this reluctance consists of the fact that film festivals which – as described above – make every effort to feel like a real festival let themselves be deterred and discouraged by the visual image or appearance this involves. And I do have to admit that perceiving 3D constructions as festivals locations really does take a lot of getting used to, as indeed does accepting avatars as being yourself and other persons. Yet for that, elaborately designed games do show that photo-realistic virtual environments are also possible. But practically speaking, this is more likely to be utopian[8].

And the development of such virtual environments takes longer than that required for a vaccine;-)

When viewed from a communications theory perspective, however, such reality-replicating 3D constructions do have the advantage that they are better able to fulfil some functions of a physical festival than do the re-productive formats mentioned above. Chance encounters, dialogue-based participation and self-determined communications and actions (’empowerment’ so to speak) on the part of the participants is possible, and even the participants’ own appearances can be specified. It is only when you have your glass filled with a cocktail at the festival bar – which is of course also a virtual environment – that you do then find yourself colliding against the final electronic frontier.

Ethical Aspects

Social media platforms and video-conferencing applications are quite intrusive from both a social and technical perspective. They pry (with a camera and microphone) into private spaces and make these available to the public worldwide. Conversely for the filmmakers involved, however, no public space arises[9]. The linguistic term for this effect is called interactive loneliness.

On a technical level, the pre-requirements for participating are often borderline, especially with (apparently) cost-free applications. And that namely when they require or involve the installation of applications that are uncontrollable by the users. Due to the monopoly position that many platforms enjoy, we have no choice but to agree to their terms and conditions even if we would prefer to not let malware and spyware become embedded in our own home office.

For these reasons, responsible handing and use of digital techniques would be desirable. When under pressure, many festivals that feel more connected with the technical and cultural practices of the analogue world tend to overlook these issues.

Ideas and Suggestions to Improve Quality

Automatic photo booth © Reinhard W. Wolf

The attractiveness of dialogue formats and other online presences will increase once their quality improves. The dreary online screen conferences recorded on video thumbnails, in which the people look like they have been photographed in an automatic photo booth from the last century (image), are something we hope soon no one will have to look at anymore. Nor have to listen to what sounds like a bad mobile phone connection coming from a bathroom.

Control room, Nordisk Panorama 2020 © Niklas G. Ivarsson, NP

The technical and personnel outlays just to provide clean audio and video for the transmission of talks and discussions is, unfortunately, not inconsiderable. Instead of using ‘consumer products’, investments need to be made in professional cameras and mikes, image-editing and sound mixers, as well as in studio personnel. Some festivals are in a position to afford this or are already well-equipped to do so (please see image above).

However, this is only halfway useful when the conversation and dialogue partners are not able to become involved in and keep up with this. And this represents an almost insoluble problem for festivals which show films from countries that are less developed industrially, as well as from independent filmmakers (digital divide). After all, even here in Germany there are regions with such miserable mobile network coverage that having the best image and sound equipment there is futile.

Without the appropriate studio and network technology, live broadcasts make little sense. They are only worth considering for festivals with an international direction that want to reach beyond their own neighbouring time zones, and that when recordings from them are released and broadcast subsequently.

Not only should video conferences be moderated, they should also have assistance. Whoever is moderating should be able to focus their concentration entirely on this and not also have to take care of the image and sound direction.

Film editing should not be left to the app. Publishing automatic recordings of talks is easy and cheap. But that’s also how they look. They resist all principles of film montage. Video conferencing apps, as successors to video telephony, are really only good for dialogues between two people (reverse shot). It is paradoxical when festivals that value the craftsmanship and aesthetic quality of films depict their protagonists as stacked tiles. A collection of picture windows in which everyone is looking into a different selfie camera or squinting obliquely at their own screen does not represent a common conversation situation. Rather, visual strategies should be conceived and practised that establish spatiotemporal continuity or cinematically convey the disparities of different locations as well as directions of gaze and dialogical relationships among the participants.

We could, in my opinion, really take a step back from recording and broadcasting video greetings and messages. They are mostly full of the exact same platitudes and, with no audience present, fade away to nothingness in the data universe.

Well-prepared talks, discussions and footage that are professionally edited are better than improvised videochat recordings. And as is already the case with some festivals, stills or film excerpts could be edited into such professionally produced works to round them off.

It would serve to improve their comprehensibility and reach if film talks and discussions were subtitled filmmakers involved[10]. Likewise, it is preferrable for filmmakers to speak in their own mother tongue and thus be able to express themselves better, than is the case in video conferences at which there is not a single ‘native speaker’ present in most cases.

It would be nice if festivals could come together and – in a task-sharing structure – produce such film talks and discussions as small films, and make them available to each other reciprocally. In this way, an archive of lively film history would be additionally created that could also be used by other parties, such as the film libraries and cinemas, for instance.

Investments should be made in better communications and video-conferencing applications that do not infringe on privacy rights or are politically compromised. Above and beyond the cost-free platform services, there are alternative telecommunication and conferencing applications that have not yet been tested by festivals and whose additional functions and features have still to be exhausted. It is to be feared that smaller short film festivals will not be able to afford or do this, especially in light of the fact that they may have adopted a ‘hybrid’ position due to the current situation and thus already have double outlays and facilities. Cooperation between event organisers could soften this aspect.

Don’t Get Discouraged!

At the start of the pandemic, I felt disheartened by how few call-ups and accesses were made to the discursive talks, discussions and similar options. Especially when compared to the festival trailers that – although just one click further – weirdly managed to get ten times the numbers of clicks everywhere [11]. When the talk or discussion about a short film attracts call-ups in the double-digit range, that really is a very low number compared to typical social media postings. The requirement here is to disengage ourselves from the attention economy of the commercial internet.

It may be comforting that at a physical festival, especially when the films in a complete programme block are discussed together, the festival visitors often do not want to participate in this anymore or simply just want to listen instead of holding discussions with the others there. On the internet, the discussions as recordings have the additional bonus that there is the chance of viewing them again after the actual event and ‘collecting points’.

(End of part one – part two focuses on online streaming models for festival films)

[1] Acronym of “Whole Earth ‘Lectronic Link”, online community founded in 1985 by Stewart Brand, among others, that belonged to the founders of the Electronic Frontier Foundation and The Grateful Dead, etc.

[2] The Virtual Community, Homesteading the Electronic Frontier, Howard Rheingold 1993

[3]Due to a lack of finance, the domain had to be sold in 2012 to a group of investors

[4] From a contribution by Reinhard W. Wolf for the first website of the International Short Film Festival Oberhausen, 1995

[5] Ditto, among others, the VirtualFilmfestival broadcasted contributions with Ken Jacobs, William Raban, Misao Sanada and Cate Shortland

[6] The technical basis consists of establishing the telephone connections on data networks (voice-over-IP), the digitisation of speech and a synchronous transmission of digitalised image recordings; in order to make the talks and discussions available to the public, the image and sound have to be recorded in a second step (capturing)

[7] Please also see “Filmfestivals: raumzeitliche Ausdehnung führt zu Verwerfungen in der Kino- und Festivallandschaft” (Film Festivals: Spatiotemporal Dimension Leading to Distortions in the Cinema and Festival Scene)

[8] There are already highly promising solutions for economically commercial purposes

[9] Please also see our articles on experiences of filmmakers

[10] Please also see “Kostenlose Videountertitelung von Online-Videos” (Cost-free Video Subtitling of Online Videos)

[11] Right at the top: The trailer of the collective YouTube festival “We Are One” with 362,000 call-ups (registered in October)

3 Trackbacks