GLÜCKSPFAD © Thea Sparmeier, Pauline Cremer, Jakob Werner

When exactly did cartoons fall behind other animation films using differing techniques? Strictly speaking, even James Cameron’s overwhelming epic “Avatar” is pure animation to a large extent, with up to 60 percent of it consisting of animated parts. The interplay of the cutting-edge VFX, CG animation and motion capture technology has little to do with a “real film” – i.e., one in which the camera captures real acting performances (fictional film) or realities (documentary). On the other hand, the drawn sheets in an analog cartoon film captured sequentially by the camera only then result in a “real film” when a consensus exists that any such film can also pass itself off as a documentary. In fact: That which is filmed or photographed also always exists before the camera as a true reality. But does that not just make all of this even more complicated?

A realization: Should I now ponder aloud about the film review’s reservations at touching upon animation film, I am inevitably stepping onto thin ice. Neither do I appreciate the artificial worlds of fantasy especially, nor have I ever really felt enthused by classic animation films. My partial ignorance here is, however, due to animation film being so rarely regarded as a subject that film reviews take seriously. Such as the “Zeit” newspaper review of Jonas Poher Rasmussen’s documentary animation “Flee” (2021), whose unique style was accorded no special mention by the critic who penned it. In this way, animation films remain pure vessels for a story with a message – and become invisible on a formal level. Or else they are elevated to a fetish by the handful of experts who have absolutely mastery over all the differentiating nuances and can effortlessly juggle terms such as Kodomo, Shōjo, Shōnen or Josei. Yet both sides, the ignoramuses and the aficionados, avoid providing some kind of aesthetic clarification to an equal extent: For the one, the style is not worth mentioning, while for the other one, the fascination is self-evident. Yet this leaves us emptyhanded as to why a specific animation film should be especially good.

As I had stayed well clear of this area to date, to prepare for this piece, I undertook some self-experimentation and penned my first ever animation film review. I chose Masaaki Yuasa’s “Inu-Oh” (2021), which we had included in the Berlin Critics’ Week screening program at the start of the year – despite my opposition to it as a selection committee member. The film’s advocate was a colleague who is highly devoted to Japanology and animation film. Yet even he was unable, taking the criteria or words of the film review as a basis, to plausibly explain as to why this film deserved to be the first animation film ever to make it into this screening program since the launch of the Critics’ Week in 2015.

Admittedly: I just do not know where to start with animation film. Yet I do know, as a programmer of experimental film screenings at the UNDERDOX film festival, that access to certain film categories is fundamentally hindered by our simply knowing too little about them. What should we expect if I were to write a review of an animation film even though I am really not versed in this? It quickly became evident: A review in the sense of a judgmental analysis (which would, of course, be quite a restrictive definition for a film critique) would not be possible. So I first took a detour into the descriptive, before then plunging into the research aspects. And as I wrote, another film came to mind that provided an important foothold for me: Sumiko Haneda’s “Into the Picture Scroll – The Tale of Yamanaka Tokiwa” (2004). Created as a documentary in the sense defined above, the filmmaker tracks with his camera along an historic scroll of pictures from the 17th century, on which an ancient legend successively unfolds. We included the film, which was shown for the first time here in Germany in 2004 at Berlin’s Arsenal Institute, in the screening program of our first ever edition of UNDERDOX, which demonstrated just how fascinated we were by this work. The intersection between document and experiment seemed astounding to us, as indeed did the surprising volte-face of creating a fictional film solely by filming a document. Yet at that time, I did not realize that this could also be an animation film.

Which is something I realized even more as I wrote about “Inu-Oh”. To animate means to enliven or ensoul, and so I traced back the “anime” word to its original meaning of breathing life into artificial worlds. The mechanical unfolding of the scroll in “Picture Scroll”, captured by the camera, takes up an early idea of cinema. From this perspective, anime as such seems uniquely suited to recounting the origins of Japanese culture and the arts – and “Inu-Oh” is concerned with exactly these beginnings, focusing on the origins of Nō theater, among others. So I now had an argument. And suddenly anime seemed like an aesthetic inevitability to me, even a necessity. My elation blossomed.

Thus, regarding animated images as an early form of cinema proved to be my salvation during this, my first serious analysis of and confrontation with animation film. Other examples then came to mind: What, for instance, is the early work “The Horse in Motion” (1887) from Thomas Edison if not an animation film? In order to determine whether a horse has all four legs up in the air at one and the same time, together with the British photographer Eadweard Muybridge, he created a chronophotographic series that was played back by means of a kinetoscope or “movement seer” and caused the photos to move – or: he animated them.

Other primitive preforms of cinema are similar. Every child knows the flipbook, and even today in film didactic courses, the students first draw and then craft and construct for all their worth. And look: With just some minimal shifts in the characters being depicted and by flipping through the images at a specific speed, the drawings gain movement. Which also represents a fascination with the animation technique and the optical illusion especially. Yet if we know too much, this effect becomes lost once more. During my schooltime, I visited the TV animation studios where the German semi-cartoon series for children called “Die Sendung mit der Maus” is made, because I was in the same class as the son of the “mouse” animator, Friedrich Streich. I thought it was amazing there, but also a disillusion. The drawers of the animation images, who were sitting in a row at a table in the studio (this was in the early 1980s), were slaving away like busy bees doing piecemeal work.

On the subject of bees. Childhood in Germany during the 1970s and 1980s did of course involve corresponding TV viewing experiences. There was Hiroshi Saitō’s “Maya the Bee” (1975-80) and “Wickie and the Strong Men” (1974-75). And there were classics, such as Walt Disney’s “Mickey Mouse” (from 1928) or Bob Clampett’s “Porky Pig” (1964-1972), as well as “Tom and Jerry” (1940-1967), created in Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer’s big studios. There were also works that came from Europe, such as Bruno Bozzetto’s “Mr. Rossi” (1960-77), Annette Tison’s “Barbapapa” (1974-77) and Zdeněk Miler’s “The Little Mole” (from 1957).

With a list like that, cartoons inevitably found a home in our childhood, and that in two respects. One striking aspect in this was and is the recurring large, bulgy eyes, found to the same extent in the Japanese anime films “Maya the Bee” and “Wickie” as indeed in all the other cartoon genre formats, be that with US, Italian, French or Czech characters. The childlikeness of the characters created here is driven by biology, as we know from the behavioral researcher Konrad Lorenz. The large saucer eyes, shifted anatomical proportions, accentuated body midline and short limbs appeal to our protective instincts and generate a euphoria of cuteness within us, one that even works with objects. Which means that the ever-popular cartoon movies from Disney, Hayao Miyazaki’s acclaimed anime “Howl’s Moving Castle” (2004), as indeed the celebrated Pixar films such as “Toy Story” (1995) or “Finding Nemo” (2003) are all just especially successful at pressing our biological buttons. And the scheme utilized in all these major productions: The immediate, intuitive reaction of the viewers is driven by the charm and appeal provided. Which is something that even works in horror movies, such as in Tim Burton’s “Frankenweenie” (2013) or Henry Selick’s “Coraline” (2009).

Yet under the omen of the film review, mistrust is certainly needed when it comes to this charm-reaction-pattern in animation films. Film reviews – and critiques in general – should expose and debunk such manipulation strategies, regardless of whether this might be the evoking of “overwhelming” emotions by using a string orchestra to perform the score, or by placing a cognitive message in the viewers’ minds by means of a suggestive editing sequence, such as in a propaganda film. For the inevitably schematic nature of a drawing is especially suited to transporting simple messages. Like in the cementing of gender roles and stereotypical looks in Disney classics, such as in “Beauty and the Beast” (1991), the embracing of the funny and pleasant fat characters in “Ice Age” (2002), or in the diversity-washing of stereotypes, such as in Disney’s “Pocahontas” (1995).

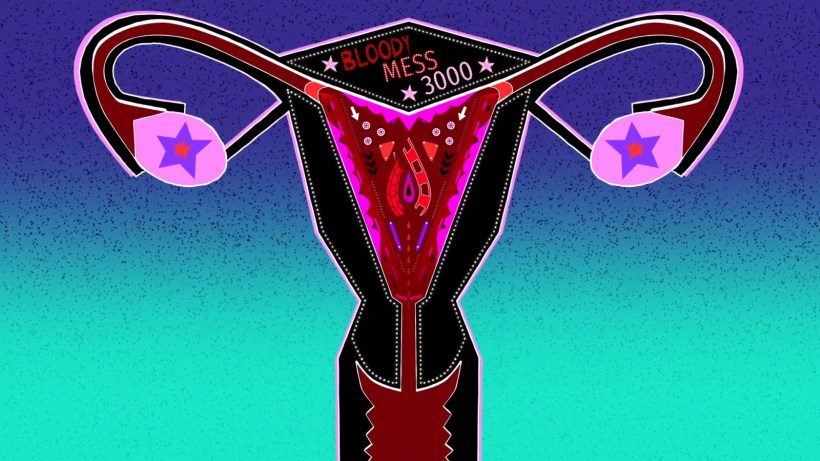

HIT THE ROAD EGG © Sabine Redlich

Drawings constitute necessary simplifications, stylizations and indeed symbolizations. And, more so, even sophisticated films intended for an adult audience often transport a “new naivety” that, as per the French phenomenologist Paul Ricoeur, displays a “prerational symbolic power”. When complex suffering is reduced to a few strokes and lines, such as in Simon Schnellmann’s quite harrowing chemotherapy short film “To the Last Drop” (2021), and gender issues become immersed in the joys of life, like in Sabine Redlich’s ovulation film “Hit the Road, Egg!” (2021) and the depilation film “Happytrail” (2021) from the trio Thea Sparmeier, Pauline Cremer and Jakob Werner, then we are also dealing with didactical symbol or placeholder films here that disseminate simple messages, regardless of how brilliant the drawings may be.

BIS ZUM LETZTEN TROPFEN © Simon Schnellmann

Fortunately, this can be found, see the flipbooks, see the Japanese picture scroll, in the early days of cinema. Lotte Reiniger’s silhouette film “The Adventures of Prince Achmed” from 1926 was a stop-motion film with real paper figures – and the first full-length animation film in history. Stop-motion is an animation technique from the early days of cinema, with Georges Méliès availing of it to tell his fantastic “Le Voyage dans la lune” (1902). Here, animation film is not some antithesis of real film. Instead, with its framings, planned sequences and editing, it is far closer to film as the seventh art. However, perhaps we should assign drawn animation film to another art form rather than the cinema –to the visual arts, for instance, or when much computer technology is utilized, to the creative arts (with games being a sub-category here). We can then focus far more on the artistic or technical accomplishments of the drawings. However, annoying “how-did-you-make-that?” museum films such as Dorota Kobiela and Hugh Welchman’s Van-Gogh thriller “Loving Vincent” (2017) or Lech Majewski’s Brueghel reconstruction “The Mill and the Cross” (2011) are not meant by this. High-quality artistic films are more likely to be on a par with those from the surrealists René Laloux and Roland Topor (“La planète sauvage”, 1973), which then quickly become labelled as “experimental” because they step beyond the childlikeness character patterns. Or even the acclaimed animation films from the painter Jochen Kuhn, such as “Sunday 1-3” (2005-12), that are consistently screened at cinema-art festivals, such as “Kino der Kunst”.

DIE ABENTEUER DES PRINZEN ACHMED © Deutsches Filminstitut Filmmuseum Frankfurt

The film review should, however, not regard drawn animation films, claymations, or those animated works crafted with much artistry as simply just being films. Whenever we want to write about them from the film review’s perspective, we should be prepared to rupture the narrowmindedness of the amassed criteria, avoid sweeping praise of the “great” drawing and “delicate strokes”, and also not kowtow before the techniques utilized – and instead soar upwards to a meta level. Or in other words, also consider what the anime causes or provokes, or perhaps why it is imposing itself on us right now. Why, for instance, is a drawn documentary such as Ari Folman’s “Waltz with Bashir” (2008) actually good? Why is Marjane Satrapi’s “Persepolis” (2007) brilliant? Why is Marc Wiese’s “Camp 14” (2012), which is drawn to a large extent, the only possibility for making the unrepresentable experienceable? And: Why is it logical and consistent that the DOK Leipzig festival selects the animation films and documentaries for parallel but separate screening programs? Yet the film review should also not shy away from naming naivety and regression in the manner in which they are found in the films. That this may even have an inherent value and charm of its own – is something also certainly worth considering. Yet when the knowledge about the films is actually not sufficient to write about them adequately, our own unease here and the related uncertainties should also be mentioned. Like in this piece. For which reason, the film critique’s fear of animation film will not diminish.