On the exhibition If the Berlin wind blows my flag. Art and Internationalism before the fall of the Berlin Wall on view from Sep 14, 2023 – Jan 14 2024 at different venues in Berlin — Neuer Berliner Kunstverein (n.b.k), daadgalerie, Galerie im Körnerpark, and Akademie der Künste am Hanseatenweg

North American Experimental filmmaker, Peter B.Hutton, once recalled meeting a woman while filming in an overgrown field near Anhalter Bahnhof. It was 1980, when Hutton spent a year in West Berlin on the invitation of DAAD (Deutscher Akademischer Austausch Dienst). The woman, a botanist, was collecting species of plants that were unique to the place, the kind that one didn’t encounter elsewhere in the city. This biodiverse uniqueness was a result of the washing away and germination of seeds and spores brought about by trains from all over Europe.

This accidental diversity of the flora in a somewhat secluded field can serve as a metaphor for filmmaking in West Berlin before the fall of the Berlin wall, facilitated by the DAAD Artists in residence program (Berliner Künstlerprogramm (BKP)).

The program was launched in 1963 by the Ford Foundation on the premise of avoiding “cultural isolation” of West Berlin and from 1965 onwards was continued by the West German Federal Foreign office’s intermediary organization, the DAAD. The BKP has invited international Artists – working in visual arts, sonic arts, film, literature – across wide ranging artistic disciplines, to foster critical reflection and research without any preset obligation to produce artworks. Over the years, the assimilation of documents, correspondences, photographs, letters, and artworks have generated a significant archive, which is the subject of the ongoing exhibition – If the Berlin wind blows my flag. Art and Internationalism before the fall of the Berlin Wall on view from Sep 14, 2023 – Jan 14, 2024 at different venues in Berlin — Neuer Berliner Kunstverein (n.b.k), daadgalerie, Galerie im Körnerpark, and Akademie der Künste am Hanseatenweg.

Damned if you Don’t © Su Friedrich

The exhibition is complemented by a film program that looks at a selection of audiovisual works by visiting filmmakers and visual artists of BKP until the fall of the wall. The featured films were either made during the residency, around the period of the residency, or—in certain cases—years in advance. In spite of this curatorial ambiguity, the films gesture towards the artists’ relationships to Berlin or Germany, or towards particular themes underlying their artistic oeuvre. What is striking about the list of BKP invitees in general is a commitment to minor and non-industrial forms of film production, resulting in films that are experimental, documentary, essayistic, and narratively complex. Take for example Swiss filmmaker Clemens Klopfenstein’s DAS SCHLESISCHE TOR (1982, 22’). Shot on grainy and monochromatic 16mm stock, it stitches together fragmented and de-narrativized street scenes from Tokyo, Hong Kong, and Berlin along with shots of the interior of the filmmaker’s studio in Berlin, set to the tune of a kitschy westernized Chinese Music – a treatise on time, travel, longing, and one’s own place in the world. The interior of a residence in a foreign land and its psychological imprints is perhaps a theme not easily shaken off by filmmakers. In Ken Kobland’s video essay BERLIN: TOURIST JOURNAL (1988, 18’), a tableaux vivant of Gustave Courbet’s L’ORIGINE DU MONDE and a gothic film playing on a TV atop a cabinet in the filmmaker’s hotel room is juxtaposed with the audio of US president John F. Kennedy’s speech at the Rudolph Wilde Platz in Berlin from 1963 where he dramatically implicated the “Communist world” vis-à-vis the “Free world”. Kobland combines footage from Walter Ruttman’s BERLIN – DIE SINFONIE EINER GROßSTADT (1927, 68’) with scenes from his hotel room, neighborhoods and the Wall to arrive at the discord between Berlin as an imaginary and real landscape—an outsider’s encounter with a city imbibing layers of history.

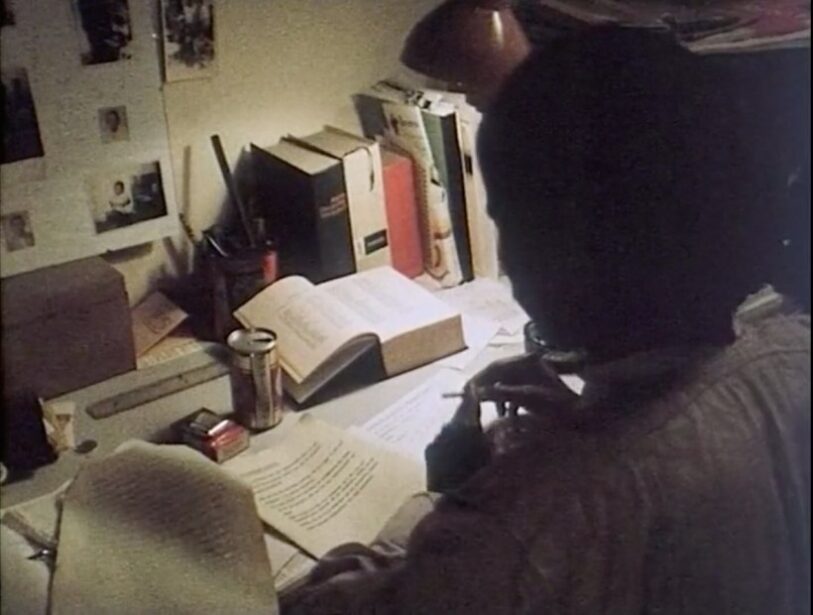

Coperation by Parts © Daniel Eisenberg

History and landscape have been central to the films of Daniel Eisenberg, who came to Berlin as an artist in residence in 1991, after the fall of the wall. His essay film, COOPERATION BY PARTS (1987, 40’), an autobiographical diary that reflects upon the legacy of the Shoah as postmemory—an experience not lived but inherited. Here Eisenberg, who was born after the Shoah and whose parents, survivors of the Shoah, had met in Dachau, explores the latencies and inscription of history by combining footage of architecture, landscape and travel across France, Poland and Berlin with an evocative text poetically rendering the lacunae of history rather than its factual description. Presented alongside Eisenberg’s film was another short film exploring the traces of a Jewish Berlin, EIN VERLORENES BERLIN (1983, 21’) by Richard Kostelanetz and Martin Koerber. Filmed in the famous Berlin-Weißensee Jewish Cemetery, a site of burial for several Jews who committed suicide under National Socialism, the film combines static, tracking and tilt shots to paint a portrait of the place combined with a soundtrack where Berliners reminisce about its historical significance.

Man sa yay © Safi Faye

Like its Jewish population, the history of Berlin is intertwined with the history of its immigrant population. And while artists from the USA are an overwhelming majority in the BKP, followed by Europeans in second place, a notable exception is Safi Faye who passed away earlier this year. Hailing from Dakar, Senegal, Faye studied ethnology and film in Paris. Her acclaimed classic KADDU BEYKAT (1975, 90’) was shown at the Berlinale Forum in 1976. Faye came to Freie Universität Berlin for a video workshop in 1976 and subsequently stayed back after receiving the DAAD grant. In her film MAN SAY YAY (1980, 60’) produced by the German Television channel ZDF, the protagonist Moussa resides in a shanty studio adorned by a poster of Angela Davis, several paintings, books such as volumes of writings by Bertolt Brecht, and photographs of his kith and kin back in the Senegal. He studies, roams the streets of the city, does odd jobs, socializes with fellow African migrants, and comes home to the affectionate letters of his relatives, near and distant, filled with longing and lists of things they would want him to get from Europe. Combining documentary and fiction, the film sketches the many paradoxes of a solitary life away from the intimacy of home.

Documenting migration is at the heart of LOTTANDO LA VITA – LAVORATORI ITALIANI A BERLINO (1975, 99’) by Videobase, a video-activist collective from Italy with Anna Lajolo, Alfredo Leonardi, and Guido Lombardi as its members. The collective spent a three-month BKP residency in Berlin in 1975. Their videos dealt with issues of eviction, factory occupation and gender justice in working class neighborhoods in Rome. In the vérité style LOTTANDO, they zoom in on the working conditions of Italian guest workers in bars, streets, restaurants, and shelters in Berlin. Using video for uninterrupted takes and deploying its capability of instant feedback to engage in a participatory form of filmmaking involving those filmed, Lottando points to the everyday challenges of life in a city where exploitative economic structure reigns.

Baroque Statues © Maria Lassnig

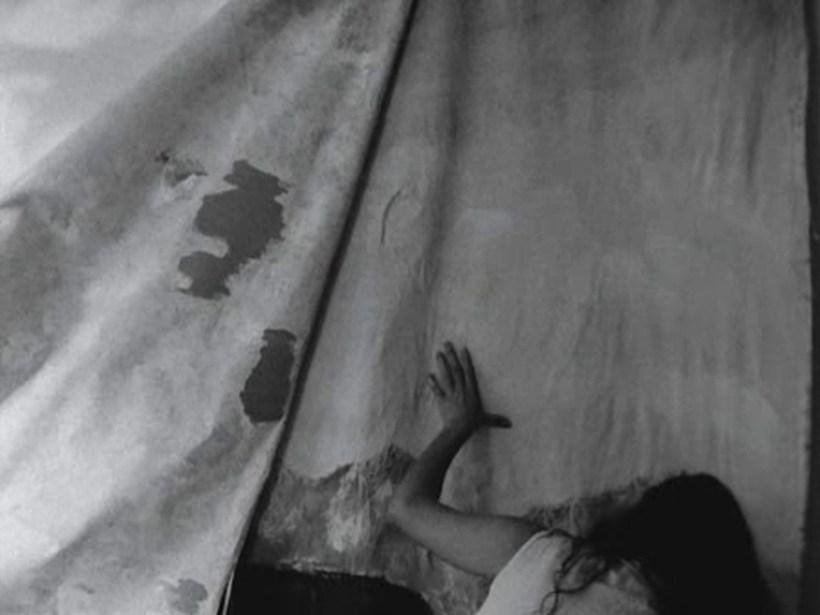

Breaking away from questions of labor and exploitation, and orienting the focus on representation and rhythms of the female body in relation to the history of painting (particularly Baroque, Surrealist, and Cubist) and dance are Austrian painter and visual artist Maria Lassnig’s two short films, IRIS (1971, 10’) and BAROQUE STATUES (1974, 15’). Extensively employing superimpositions in images and setting them to forceful soundtracks, these films seem to hark back to an older queer psychedelic moment and its quest for sexual emancipation in avant-garde films from the 1960s. The formal accomplishments of Lassnig’s films might seem rather sedate today but they remain crucial subversions in the male dominated experimental film scene in Vienna at the time. Lassnig’s films were presented in a single program with a masterwork by Su Friedrich, DAMNED IF YOU DON’T (1987, 41’). Here Friedrich meticulously deconstructs the oppressive structures of the Catholic Church, taking Powell and Pressburger’s BLACK NARCISSUS (1947, 100’) and Judith Brown’s novel IMMODEST ACTS: THE LIFE OF A LESBIAN NUN IN RENAISSANCE ITALY (1986) as its departure points. The film shot in monochrome subterfuges narrative expectations and creates layers of montage between images and sound. The shots alternate between documentary, refilmed footage (from Television) and optically printed images, while on the soundtrack we hear a casual feminist analysis of BLACK NARCISSUS’ plot, interviews with nuns and readings from Brown’s novel. The images only ever vaguely articulate their relationship to the spoken word. Friedrich would come to Berlin for a BKP residency a few years later in 1994.

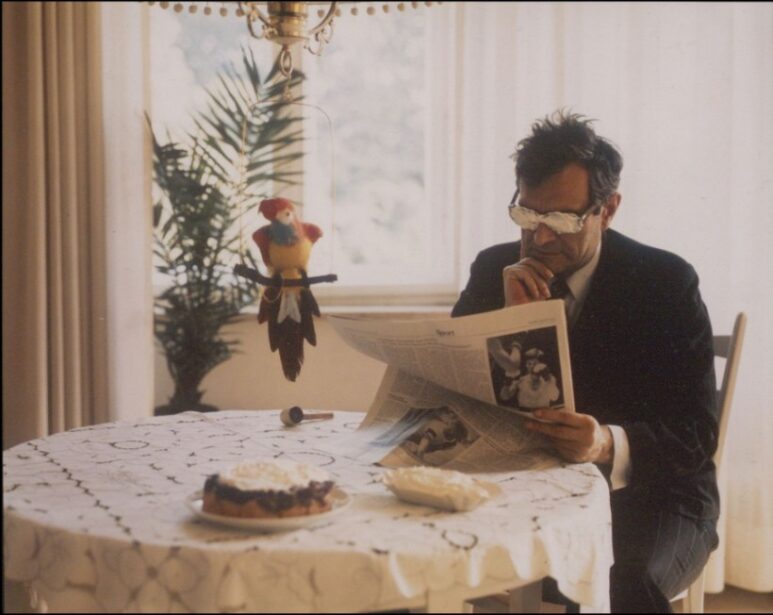

Berlin oder ein Traum mit Sahne © Marcel Broodthaers

The two most fascinating films shown as part of the film series were made by conceptual artists doubling up as filmmakers- the Belgian Marcel Broodthaers’ BERLIN ODER EIN TRAUM MIT SAHNE (1974, 18’) and the American, Lawrence Weiner’s A SECOND QUARTER (1975, 88’). Both films were finished during the residency period in Berlin, in consecutive years. Broodthaers was a prolific filmmaker who made approximately fifty films between 1957 and 1976. Carrying over his interests in objects, artifacts and text into film, Broodthaers assimilated all sorts of influence from early cinema – surrealist, slapstick and anarchist. According to art critic Bruce Jenkins, in BERLIN ODER EIN … “Broodthaers revisits the central theme of the (Jean) Vigo film (L’ATLANTE (1934, 65’)) – the connection between imagination, faith, and freedom and condenses them into the Keatonesque figure of the dreaming artist.” The film was first shown as part of the solo exhibition devoted to Broodthaers at the Nationalgalerie, Berlin in 1975.

Weiner’s A SECOND QUARTER forms a diptych with his earlier film, A FIRST QUARTER (1975, 85’) which was shot in New York a couple of years prior. Both films are structured around three characters and their social behavior but without conceding to the cause-effect rationality – so integral to the development of a narrative arc in fiction films. In A Second Quarter, we encounter scenes mostly shot indoors with occasional views of streets and abandoned grounds in West Berlin, and conversations (if one can call them that) among the protagonists, where they recite Weiner’s linguistic pieces as fragments of sentences. Such deployment of speech, where its role as language is minimally retained (as opposed to reducing it to pure sound), facilitates not only a severance from the image, but also negates continuity within speech itself. This autonomy of speech in its fragmented demeanor transgresses even its most radical peers: the films of Jean-Luc Godard, Marguerite Duras, Jean-Marie Straub and Danièle Huillet.

Kristina Talking Pictures © Yvonne Rainer

But perhaps the closest to mobilizing speech in a similarly militant manner is Yvonne Rainer, whose films from the 1970s are formally the most complex of American filmmakers, once one begins to uncloud their understanding of formalism from the minimalist straitjacketing endorsed by Clement Greenberg. Rainer, a dancer and choreographer, studied with Martha Graham and Merce Cunningham in New York. She received the BKP grant in 1976 as a fellow in the film program, the same year she finished KRISTINA TALKING PICTURES (92’). Rainer, like Weiner, invests in narrative if only to rip it apart by employing disjunctive strategies (fragmented speech, destabilizing the actor-character relationship, a highly discursive frame of geopolitical references) that render the concretisation of the film’s primary characters (the Hungarian lion tamer in New York, her lover—a seaman…) impossible. Allusion to the Shoah lurks on the periphery of KRISTINA TALKING PICTURES but Rainer would return to Germany as a subject, or more specifically its history of state repression, in her next film, JOURNEYS FROM BERLIN/1971 (1980, 125’). In here among other things, one senses Rainer (whose parents were anarchists) attempting to historicise the political action of RAF by connecting it to the Russian anarchists. As one character says in the film,

“the RAF didn’t rob banks just to get money. They believed in lawbreaking as something positive. Meinhof wrote that the progressive significance of department store arson lies in the criminality of the action … So that must have applied to robbing banks as well. In their way they were just as nihilistic as the 1870s Russians.”

This film program successfully demonstrates the rich variety of genres and styles that mushroomed under the BKP fellowship. But like the exhibition itself, this is only a starting point which hopefully would lead to a more complete retrospective of films. Perhaps by loosening the reliance on digital projection, some of the rarely shown works could reach the audience, such as JUST WAITING (1975, 10’) by Stephen Dwoskin, NOTES ON BERLIN: THE DIVIDED CITY (1986, 25’) by Arthur and Corinne Cantrill, and DIMINISHED FRAME (1970/2001, 24’) by Robert Beavers to name a few. At least some of Berlin’s multicultural film and art scene compared to the rest of Germany can be attributed to programs such as the BKP. What is of further importance though, is the probing of the parapolitical ambitions of such a program in the cold war era, in order to unpack the finer political nuances enshrouded within that one term that strokes the cultural propaganda of the “free world”, “Freedom”. Particularly in light of discoveries such as the SS past of Werner Haftmann, the ex-Director of the Neue Nationalgalerie, and a member of the jury that selected BKP fellows for ten years.