Performance of Mbaracás by Gaetano (2022) as part of “It’s rather a verb,” curated by Sirah Foighel Brutmann & Eitan Efrat, at EMAF 2022 © Angela von Brill

Film festivals, or more precisely, the film-cultural, social and economic roles of film festivals have become the subject of discussion, and that not just since the corona pandemic. The unique circumstances under which their production, reception and funding conditions became reconfigured over the last two years have merely accelerated an awareness by the public that already began with the founding of the “Festivalarbeit gerecht gestalten” initiative[1] in 2017 and the merger of – by now – more than 100 organizations to form the German AG Filmfestival lobbying association in the autumn of 2019. In line with this, a panel discussion entitled “What Is the Point of Film Festivals?” was held by the AG Kurzfilm German Short Film Association last year at the invitation of the Torino Talents and Short Film Market. The text you are reading is based on the keynote speech I gave there, broadened to include considerations that extend beyond the German context. Doing so, I hope especially to redirect the aim of the question addressed by the panel, “What is the point of film festivals?” into that of, “Festivals – for whom actually?”

Coexistence

The reason why it is also important to speak about festivals right now is because new festivals continue to emerge and claim their place in a field that is already brimming full. In Germany, there are almost 450 film festivals, more than 100 of which focus more or less exclusively on the short film format. Even during the pandemic years, new festivals were launched. Thus, the intention here is to give consideration to having a new kind of festival ecology – in the sense of organizing a more sustainable kind of festival, where livelihoods and work are secured, yet which also permits and enables the coexistence of highly diverse festivals, each of which has established and cultivates its own niches.

Important motivations and incentives for this could be provided by the AG Filmfestival association. As an independent lobbying body, it represents the interests of film festivals as a primary location for film exploitation, exchanges and education, attempting to assert these aspects more powerfully in the related legislation, and striving to have networking and knowledge transfers between festivals. When it was founded, a Code of Ethics was drafted that defined film festivals under Point 1 as:

Multi-day public events held annually or biennially. They are characterized by an artistically driven curatorial purpose and a programmatic profile. They are places of encounters. They support and foster film culture and filmmakers. Having the best projection possible of cinematic works in cinemas or cinema-like situations is part of their self-image. The film festivals serve as forums for having exchanges and forming opinions.[2]

This definition of their core competencies already reveals that festivals are – and want to be – more than their film programs. In fact, it has always been the film mediation work, in other words, the discussions and exchanges held about the films being screened and their filmmakers, that is a distinguishing feature of festivals compared to a normal visit to the cinema. Furthermore, film festivals are places in which cinematic history and working with film as a material and a technology can be experienced immediately and directly. The fact that they are also increasingly becoming places of public debate about cultural policy and social issues seems to be due to a growing politicization of the cultural scene, and that not only in Germany, or at least a result of the tendency to again accord powerful consideration to film and art as factors in social and political decision-making processes.

Aufführung von José Val del Omars Fuego en Castilla (1961) im Rahmen von „SPECTRAL: Unburdened Recollections“, kuratiert von Esperanza Collado, beim EMAF 2023 © Angela von Brill

At the same time for quite a while now, a multiplication of the presentation formats can be observed; formats that are not originally intended for screening in the cinemas, such as VR presentations, lecture performances, expanded cinema, projections in urban spaces or installations, as indeed music acts of all kinds. This drive to diversify has developed from the apparent requirement for festivals to distinguish themselves more powerfully within an abundance of alternative cultural event options – the effect of which is, paradoxically, that the individual festival profiles are becoming ever-more similar. And do festivals – especially short film festivals – not also have to position themselves increasingly vis-a-vis an art scene, in which artists’ moving images are being regularly exhibited, and that often long before festivals “discover” these works? The relatively new invention of the “festival premiere” label in the program announcements is a reaction to the circumstance whereby festivals are no longer the first and most important screening location for certain works, but rather art exhibitions.[3] By the way, exhibition spaces or organizations run by artists also hold recurring, multi-day, publicly accessible, carefully curated film events aiming to have exchanges and form opinions, screened in cinemas or cinema-like situations (or in other words, de facto film festivals).

The extent of the target-group specific funding differentiations occurring over the last few years, often motivated by strategic considerations to secure such funding, can make it difficult at times to comprehend the programmatic aims of individual festivals. And this development is also not necessarily beneficial when it comes to the working conditions at festivals. When their requirements increase while their budgets remain the same, more or less, or their economic situations are insecure – and the vast majority of the festivals in Germany do not receive continuous institutional funding – it is only to be expected that the sustainable and fair employment of festival staff is thus not possible. And, unfortunately, nothing is changed either by having a “Fair Festival Award,” which, while it creates new competitive conditions (even if its organizers would dispute this), contributes little to a discussion about successful measures from which everyone could benefit, including their publication.

Meanwhile, more and more initiatives are occurring to create greater structural sustainability, such as job and resource sharing, meaning that a staff position is, for instance, funded over the year by two or more festivals, the technology is jointly acquired, or spaces are rented by several organizations and used alternately. However, all of this presupposes that the related festival events are located in close proximity to each other and their festival time schedules are compatible A similar situation occurs when you have festivals running at similar times and which have a joint invitation policy. While this type of sharing is certainly useful, exchanging personnel in content-related areas can also become problematic. Having curators and programmers moving from one festival to the next (which they are not infrequently dependent upon to finance their livelihoods) results not only in the danger of watering down the related festival profiles, but also in according individual program decision-makers a problematic concentration of power.

But who exactly are in these teams? When it comes to their composition, by now festivals have achieved a relatively high level of diversity, and even their juries, panel discussion members, selection committees and other short-term positions are filled in a far more diverse manner than was the case just a few years ago. Yet for that, they clearly lag behind at the level of their permanent employees and especially the festival management. Only a few people are able to afford to work over a longer period for a festival in order to qualify for a managerial position doing so. Paradoxically, even an underpaid festival job thus still remains a privilege. In any case, the inertia found within the traditional structures is considerable, and right now it seems that marginalized communities are more likely to develop their own event structures, rather than wait for festivals to approach them so as to “integrate” them and their expertise.

Curatorial Ethics

In the discussion about fair, more sustainable working conditions, likewise the perspective of the artists is all too often ignored – and that even in the first comprehensive publication about the German film festival landscape, in which the festival organizers especially have their say.[4] Even if no film rental fees in this world would ever secure someone’s livelihood permanently, festivals must reward artistic work more appropriately and thus fulfil their responsibility for those artistic careers, upon which they base their own reputation. Eli Horwatt worded it as follows in World Records Journal:

The economic model underwriting most festivals works like market futures, as the unspoken promise to a filmmaker rests in the hopes of receiving the prestige, press, or distribution that festival exposure might offer. But any money trading hands at this event will likely not touch the person providing the film. It begs the question: Who are film festivals for?[5]

This question becomes all the more urgent when, as Genevieve Hue notes, apart from festivals, for certain films – and especially for short and experimental formats – there are only a few alternative marketing and exploitation opportunities, with none of them ever being lucrative: “There is little to no hope of a licensing deal following the festival, and while some bigger titles might get a museum or microcinema event, the short year that a film travels the festival circuit is likely the only time many films will ever screen publicly.”[6]

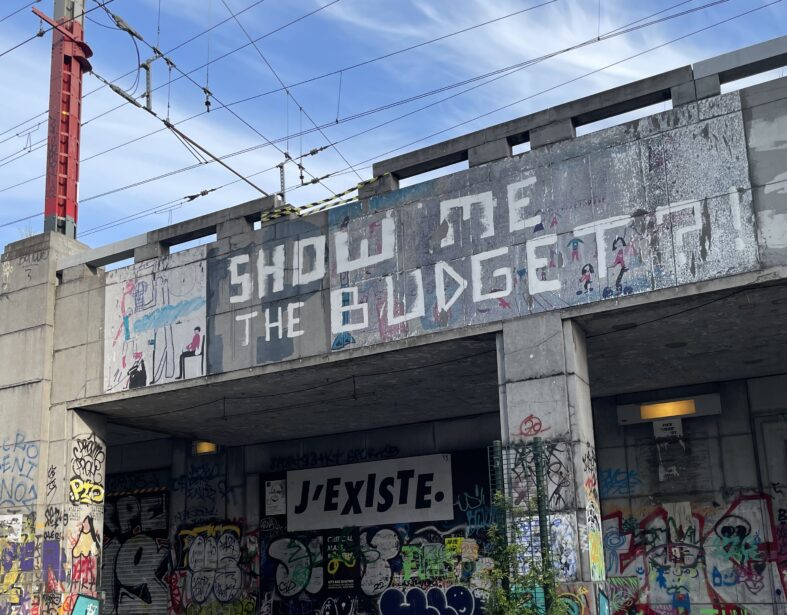

Brüssel 2022 © Katrin Mundt

While a set of recommendations for fairer artist fees has already been compiled for the visual arts in Germany,[7] the majority of the film festivals avoid this subject – even if several smaller festivals especially pay fees or specifically consider doing so. In this context, it is also worth taking a look at Canada, where the Independent Media Arts Alliance has developed a highly differentiated guideline for fee payments for artistic and curatorial work, which can serve as an orientation, even if individual adjustments are of course necessary.[8] What these examples also reveal is that long-term changes are only then possible when the support and funding institutions also acknowledge that the fair payment of cultural work is a necessity and they reflect this in their funding allocations..

In his essay “Who Cares about Cinema?,” the film critic and curator Dennis Vetter diagnosed the situation as follows:

Even as care—in the contexts of class, race, gender, and more—becomes increasingly relevant to cinematic representation, the actual work of making cinema, from film festival programming to below-the-line production jobs, lags far behind. Recent steps forward have notably been based on personal initiatives rather than sustainable models within the system.[9]

One scenario currently under discussion so as to relieve the strain on human, financial and natural resources is to downsize events. This option clearly seems to be less attractive for smaller festivals than bigger ones, as any further reductions in their programs could become a problem for the smaller festivals’ visibility. Yet what can be wrong with festivals bidding farewell to the pressure of constantly having to grow more and claim new territories for themselves? Or in other words, not downsizing, but rather diversifying and experimenting within their existing frameworks; reappraising their own strategies and curatorial preferences; involving new voices in the production of a proven format; repeating successful projects at other locations?

In fact, these considerations about downsizing on the part of the festivals also seem to correspond to a tendency among the audiences. They are less willing than in the past to subject themselves to those jampacked programs that have fundamentally characterized festivals to date and which, in my personal experience, also constitute what is special about a well-curated festival: A kind of overwhelming that often still lingers days or weeks later, raising questions as we hold our verdicts in limbo. According to some festival visitors, this is where more rest breaks, spaces for reflection and opportunities for discussions should now be provided. And the film festival as a public event format should react more sensitively to personal stress limits. Yet what else can festivals impose on their audiences in accordance with this? Or is the unwillingness to be challenged by film and art the real imposition here?

Impositions

As short film festivals notably involve a large number of young artists and contributors, it seems that particular care is required in communicating their own programming intentions, concerns and possibilities. And this is especially so in a time when there are ever-increasing calls for exchanges with those persons who decide about the public visibility of art and its makers, as well as the desire to have more transparent dealings with institutional structures, financial resources, and political programmatic aspects. How can festivals face these new challenges anew? Or are the claims and aspirations that filmmakers have of festivals merely increasing at present? It is hard to provide sweeping answers to these questions. Which, however, does not free the festival organizers from the requirement to question their practices to date anew and make themselves more prone to these concerns – which is not that much different to what the artists do who expose themselves to their judgements.

One thing filmmakers certainly can and should demand is to have the best possible presentation of their works. Which in the cinemas seems self-evident to us. However, for the “cinema-like situations” named in the Code of Ethics from AG Filmfestival, and even more so for performances, installations or interactive formats beyond the cinemas, this is by no means always the case. Inadequate technology, untrained or poorly briefed personnel, too short set-up and rehearsal times, or unsuitable premises often lead to situations where these works cannot be experienced in the manner intended by their makers.

And what can film festivals expect of each other? Selecting films always means making the selection for a specific festival. And as long as there are festivals that insist on having premieres, there are other ones whose programming is affected either directly or indirectly by this. Even if this contradicts my personal understanding about the distribution and accessibility of media arts, there are examples of how an exchange can occur between festivals about their programming decisions, without putting the filmmakers under pressure to decide on having their premiere at one or the other festival doing so. The issue about having a “fair festival” also includes the implication of how festivals act and behave competitively among themselves, or how openly and collegially they communicate their own priorities and claims to exclusivity.

In any case, festivals’ significance has shifted in recent years. Smaller festivals have been able to gain new audiences thanks to their online programming, thus permitting them to also raise their profiles vis-a-vis larger festivals. At the same time, however, among younger audience groups especially, the idea is fading of what on-location festivals are and how they work, what kinds of sociality and intimacy they enable and facilitate, how they fill time and space, enrapturing our perceptions (or have they just become less attractive for them?). Thus it seems that the festival as a cultural practice has to be learned anew under these changed conditions – and that perhaps also by the festivals themselves.

[1] “Festival Work Fairly Organized” initiative

[2] https://ag-filmfestival.de/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/AG-Filmfestival-CoE.pdf

[3] Vgl. zu dieser Diskussion Chris Kennedy: „Platform, Showcase, Gathering, Exchange. A Conversation about Film Festivals with Erika Balsom, George Clark, Chris Kenndy, Eduardo Thomas, and Koyo Yamashita”, in: Federico Windhausen (Hg.), A Companion to Experimental Cinema, Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Blackwell 2023, bes. S. 434 ff.

[4] Vgl. Tanja Krainhöfer / Joachim Kurz (Hg.): Filmfestivals. Krisen, Chancen, Perspektiven, München: edition text + kritik 2022. (siehe Resenzsion auf shortfilm.de von Luc-Carolin Ziemann)

[5] Eli Horwatt, „Who Are Film Festivals For?”, in: World Records Journal, Issue 6: https://worldrecordsjournal.org/who-are-film-festivals-for/

[6] Genevieve Yue, „The Accidental Outside“, in: World Records Journal, Issue 6: https://worldrecordsjournal.org/the-accidental-outside/

[7] Vgl. etwa das Berliner Modell für Ausstellungshonorare: https://www.bbk-berlin.de/sites/default/files/2020-01/bbk-berlin_Berliner-Modell-Ausstellungshonorar_Stuttgart_Mai2017.pdf

[8] https://imaa.ca/source/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/IMAA-fee-sched-2020-23-with-approval-en-2023.pdf

[9] https://www.filmcomment.com/blog/who-cares-about-cinema-film-festivals-film-workers-dennis-vetter/