MARABUNTA (1967) Registro documental, original 16 mm © Narcisa Hirsch

The synonymous usage of the terms “experimental film” and “avant-garde film” is a relatively recent phenomenon: In Germany, designating a work as “experimental” had a negative connotation for a long time. This is related to the situation whereby in the turbulent 1960s, influential writers such as Hans Magnus Enzensberger (Die Aporien der Avantgarde/The Aporia of the Avant-Garde, 1962) or Siegfried Kracauer (Theorie des Films/Theory of Film, 1964) demanded of art, and indeed in general, that it should not occur “remote from everyday life” either parallel to or outside society, but rather assume responsibility. As per their interpretation, avant-garde art had a social value; the experimental was, by contrast, of a non-binding nature and thus had “worthlessness” attributed to it. From the end of the 1960s to the mid-1970s, a “new wave” emerged aesthetically across the complete American subcontinent, such as the Cinema Novo in Brazil or the Tercer Cine in Argentina, and with it key works of Latin American cinema that were defined as avant-garde. In fact this concerned committed art that was intended to liberate cinema from its commercial constraints and all of Latin America from the shackles of neoliberalism, as indeed from the military dictatorships then proliferating.

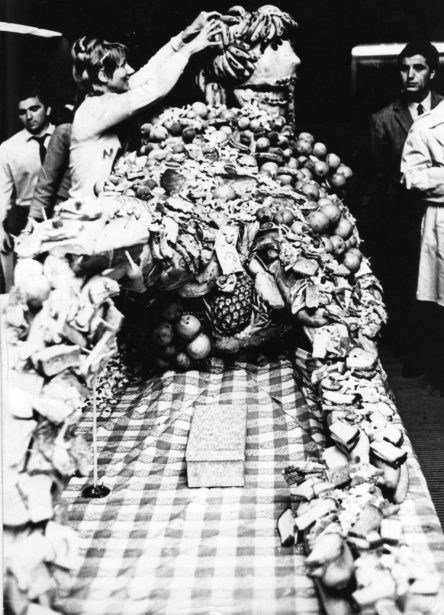

The worldwide canonisation of Latin American avant-garde film entrenched itself in Germany – and that at a point in time when the publicist Peter B. Schumann began his work with the Berlinale. He opened the festival with two film series for Neue lateinamerikanische Kino (New Latin-American Cinema) and published authoritative manuals on Latin-American (avant-garde) film – with self-explanatory titles such as Kino und Kampf in Lateinamerika (Cinema and Struggles in Latin America). Linked to this canonisation process of militant cinema resulting from these publications, which still count today among the standard film-history works internationally, is a regrettable non-consideration of Latin-American experimental film, whose most important representatives include Narcisa Hirsch (born 1928) and Marie Louise Alemann (1927 to 2015). Both Narcisa Hirsch and Marie Louise Alemann were born in Germany, but already had to leave the country in their early adolescence after the seizure of power by the National Socialists. They got to know each other in the mid-1960s in Buenos Aires where their families had found a new home, and initially appeared before the public with performances and (illegal) happenings, such as the “anthropophagic ceremony” Marabunta (1967).[1] Subsequently, the two of them created an oeuvre that revealed an extraordinarily wide aesthetic and conceptual spectrum and established them from the mid-1970s as protagonists of the so-called Grupo Goethe. The members of the Grupo Goethe – who, in addition to Hirsch and Alemann, included Claudio Caldini, Juan Villola, Horacio Vallereggio, Jorge Honik or Juan José Mugni – did not necessarily attest to a common style. But the filmmakers were associated by their friendship, the occasional cooperative work, and especially through the institutional framework of the Goethe Institute.

MARABUNTA (1967) Registro documental, original 16 mm © Narcisa Hirsch

In Argentina’s increasingly repressive political climate, the Goethe Institute, which was under the control of the German Federal Foreign Office politically-speaking – and due also to the German roots of Narcisa Hirsch and Marie-Louise Alemann – provided a protected space in which they were able to present their “underground cinema”. In addition, artists such as Jeanine Meerapfel, Jutta Brückner, Peter Lilienthal, Werner Herzog, Werner Schroeter and Werner Nekes were invited to it. They offered workshops that facilitated intercultural exchanges. The Goethe Institut was clearly taking a political stance and position here – through the selection of the guests[2], and even through the selection of the retrospectives shown[3], and deliberately risked diplomatic scandals doing so – such as when the Schroeter workshop “Tango y realidad en Argentina en 1983” ended with the expulsion of the director from Argentina.[4] On an artistic level, the Werner Nekes workshop in 1980 influenced the Grupo Goethe the most: Together with Nekes, Narcisa Hirsch created the short film La noche bengali (1980); in an interview conducted by email, Claudio Caldini mentions that Nekes’ works had a formal influence on his pieces, such as Un enano en el jardín (1981), Gamelán (1981), Tiempo cerrado (1982), La escena circular (1982).[5]

LA NOCHE BENGALI (1980) original 16 mm © Narcisa Hirsch / Werner Nekes

While it is true that, unlike their compatriots who were labelled avant-garde filmmakers, the directors in the Grupo Goethe did not attack the ruling military dictatorships directly, their works were still regarded as latently subversive; quite simply because the military just did not understand the free form of their films. And at that time, this was enough to become suspect.

Narcisa Hirsch’s films, which were shot on the “intimate” Super 8 format into the 1980s, reflect the director’s preoccupation with music, literature, the visual arts, mysticism (Rumi, 1995/1999) or psychoanalysis (Pink Freud, 1973). She was more moved by the sentiments, atmosphere and impressions in the impressive landscape of southern Argentina (Patagonia, 1972/1973; Diarios Patagónicos 1972/1974), as indeed by empathy and sensory perceptions (Ama-Zona, 1983), than she was by direct political agitation.

Yet for that, the political is present as a trace in her films. Various works by her, also including early pieces, reflect political events, frequently only as quotations that have to be decoded and interpreted. Come out from 1971, for instance, an homage to the Canadian filmmaker Michael Snow, dissolves – using minimal camera movements and changes to the framing – to a microscopic view of the pick-up arm on a record player, on which a vinyl record is playing from the minimalist music pioneer Steve Reich. This accords the film a contemplative quality. The piece by Reich consists of a single sentence, “I had to, like, open the bruise up, and let some of the bruise blood come out to show them,” that is repeated, fragmented and distorted. While an ever-larger framing becomes visible on the visual level, the loop on the sound level becomes more and more compressed, until only the words “come out” remain partially understandable. Narcisa Hirsch removes the sentence (which comes from court testimony given by a proven innocent and arbitrary victim of racist police brutality in the southern states of the USA) from its context and transfers it into her own surroundings: In 1971, Argentina was ruled by a repressive military dictatorship, during which people would be picked up from the street and arrested just because of their appearance.

AMA-ZONA (1983) original Super 8 © Narcisa Hirsch

And can the mythical female warrior in her film Ama-Zona not be a reference to the courageous female fighters for human rights during the military dictatorship (1976 to 1983), the Madres de la Plaza de Mayo? The reception of her films calls for active viewers who have to link together the various connections (including heterogeneous ideas and forms at times) for themselves. This is also true for the pieces by Marie Louise Alemann, which work with a symbolic language that is open at times and enigmatic at other times and has to be decoded by the viewers, or which create contrasts and antagonisms on the visual and sound levels that have to be resolved intellectually by the recipients. Alemann’s more performative films, which have their starting point in autobiographical scenarios (e.g. Escenas de mesa (1979) or Autobiográfico 2 (1974)) are frequently concerned with transformation processes, self-liberation or breaking out of traditional rituals; we can, however, also recognise a political perspective on gender-specific questions that deconstruct the gender roles which were, for instance, being propagated by the military at that time. A queer cinema is anticipated in Legitima Defensa (1980), while the short film Umbrales (1980) implies intersectional repression and experiences of being in exile.

Despite the privileged and influential status Marie Louise Alemann had[6], her works could not be screened in public until 1983, meaning that the Goethe Institut not only offered the experimental filmmaker logistical support, but also literally a space of freedom: “The screenings and discussions of experimental film in the late 1970s at the Goethe Institute of Buenos Aires […] constituted one of the scarce expressions of radical dissidence and resistance to the official culture of the dictatorship in Argentine cinema.”[7] The directors in the Grupo Goethe wrote “secret history” in the sense of Jorge Luis Borges that appeared in no chronic for a long time, but which supplemented and offered new perspectives on the canonised film history of political cinema in the 1960s and 1970s. Belated honouring of the Grupo Goethe has, however, occurred and been sustained through various national and international retrospectives, beginning with the 2010 showcase event from Claudio Caldini and Narcisa Hirsch in MALBA (Museo de Arte Latinoamericano de Buenos Aires); through academic publications[8], or through the documentations Hachazos (about Claudio Caldini) from Andrés di Tella (2011); Butoh (about Marie Louise Alemann) from Constanza Sanz Palacios (2013); Reflejo Narcisa (Silvina Szperling, 2015) as well as Narcisa (Daniela Muttis, 2014).

ALEPH (2005) Beta SP © Narcisa Hirsch

The history of Argentinian experimental short film is fragmentary and episodic. A new chapter, which is certainly capable on a formal level of building upon the history of the Grupo Goethe, is currently being written by directors such as Ernesto Baca, Pablo Marín, Paulo Pécora, Magdalena Jitrik, Leandro Listori, Melina Parfundi, Daniela Muttis or Melisa Aller. The latter was even represented this year with her film Caída (2019) in the competition section of the International Short Film Festival Oberhausen. Narcisa Hirsch is also still active even at 91 years of age. Her latest work is entitled Kosmos: The Uncertainty (created in cooperation with Ruben Guzmán and Robert Cahen in 2018). She has already revealed what her “cosmos” consists of in her Borges adaption El Aleph (2005). Here, she reduces the plot in the short story from 1949 to 60 images in 60 seconds that she underscores with an off-screen voice. In both the story and the adaptation, the entire cosmic space is unified in a single point, in the “Aleph”. Narcisa Hirsch’s “Aleph” shows images from the films she shot over the course of 30 years.

[1] Marabunta was documented by Raymundo Gleyzer, one of the (canonised) filmmakers whom it seems paid with their lives for their activism under the Argentinian military dictatorship from 1976 to 1983.

[2] Peter Lilienthal’s films, for instance, were banned in Argentine until 1983.

[3] The Argentinian sociologist Beatriz Sarlo recalls that during a visit to the Goethe Institute: “I saw Germans who left cursing and swearing in the middle of a Fassbinder film. […] The German community, just like all the foreign communities, was reactionary. At that time during the dictatorship, the institute presented the most revolutionary films to them from Fassbinder, Wim Wenders – he’s not that revolutionary, but the first films from Wenders were – and Alexander Kluge. In this way the institute won us over, courting us Argentinians to such an extent that we stood in queues just to get inside the cinema auditorium – and prompted the German community to leave it.” Quoted from Anna Kaitinnis: “Botschafter der Demokratie. Das Goethe Institut während der Demokratisierungsprozesse in Argentinien und Chile” (Ambassadors of Democracy. The Goethe Institute during the Democratisation Process in Argentina and Chile). Wiesbaden 2018. p. 164.

From 1979 to1985, Marie Louise Alemann even worked as a curator for the film department at the Buenos Aires Goethe Institute and thus played a decisive role through her involvement in the selection of the guests invited. During the 1970s as a journalist, she reported on the Berlinale for the Argentinische Tageblatt newspaper. She got to know many of the filmmakers invited during her trips to Europe.

[4] This scandal is documented in the article “Las alas del deseo” from Mariano Kairuz in the Radar culture section of the Página/12 daily newspaper from 11.08.2013, written for the first complete showcase event of the films by Werner Schroeter in Argentina. Schroeter left the protected space of the Goethe Institute with his camera and conducted camera interviews with members of human rights organisations, for instance. Although the military had been on the defensive since losing the Islas Malvinas/Falklands war (1982), the Head of the German institution was informed that the Goethe Institute (which is located in the centre of Buenos Aires city) would be blown up if Schroeter did not leave the country immediately. Please see: https://www.pagina12.com.ar/diario/suplementos/radar/9-9049-2013-08-17.html (last accessed on 28.05.2019)

[5] The interview was conducted by email on 29.05.2019.

[6] Marie Louise Alemann married into a politically influential newspaper publishing family that also supplied a state secretary and a minister under the last military dictatorship (1976 to 1983). Thus she was protected from repressions.

[7] Quoted from Andrés di Tella. Di Tella also describes the fates of directors from the periphery of the Grupo Goethe, who received no institutional support and had no creative freedom: “One of Claudio Caldini’s closest friends, filmmaker Tomás Sinovic, […] was abducted by the military along with his films, never to be seen again.” Andrés di Tella: “Experimental Film”. In Directory of World Cinema: Argentina (Eds. Beatriz Urraca/Gary M. Kramer), p. 235 to 239. Here: p. 236.

[8]One can name, for instance, the monography Narcisa Hirsch: cátalogo (Eds. Alejandra Torres, Buenos Aires 2010), the recently released anthology Ismo Ismo Ismo (Eds. Jesse Lerner/Luciano Piazza, Oakland 2018) or the publications of Federico Windhausen. The latter also manages the cinematic legacy of Marie Louise Alemann.