Sucessful documentary “The Rabbit Hunt” (USA 2017) © Patrick Bresnan & Ivete Lucas

Based on the impression that just a handful of short films take the lion’s share of awards and honours each year all over the world, we decided several years ago to publish here on our website an annual review of the past year’s award-winners. By analysing the prize-winners listed over the year in our “Awards” section, we are able to quantify this subjective impression using objective figures. Now it’s time to take a look back at the year 2017.

Listing the winners invariably results in a kind of Hit Parade of film. This sort of ranking can of course not be used to assess the artistic quality of films, but it does indicate their popularity as measured by the votes of expert juries and viewing audiences. Ultimately these are market data. The accumulation of awards cannot really be interpreted as an indication of objective judgements on quality.

An overview like this also yields some indirect findings, regarding for example the production volume in the various countries. In particular, the evaluation measures the success of short film production in a specific country compared to others.

Basis for the evaluation

All honours and awards were analysed that were mentioned in the “Awards” section on shortfilm.de during 2017. This accounts for just over 1,700 awards this past year. We naturally do not publish all prizes and awards conferred on short films everywhere in the world.

Only the major short film festivals with international competitions are reported. Events with an exclusively national or regional focus are not included. We do however report on national film awards such as the German Short Film Award and the Césars in France. In 2017, awards given in nearly 60 countries were published on the website.

We usually list only the major prizes, but for a few of the larger festivals we also include honourable mentions. As a rule, only short film festivals are taken into account, with the exception of major international feature film festivals with a short film competition such as Cannes, Berlin and Sundance.

Overall, we reported in 2017 on the jury decisions in 312 festivals or competitions – 66 of them in Germany. Due to our own geographical location, German as well as European festivals and competitions are over-represented. But the short films cited come from countries across all continents and regions of the world.

Strong production countries

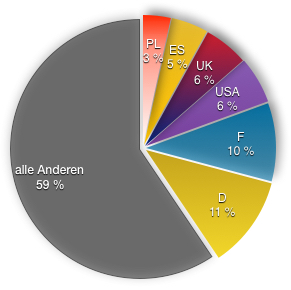

Of the awards published on our website in 2017, the most by far went to films made in Germany (199 awards), France (173), the USA (140), the UK (84), Spain (72) and Poland (59). Co-productions are not included in these figures.

Chart: Proportional success rate by country of production (6 top ranked and all other countries)

The countries at the top of the list and also the number of prizes have changed little over the years – and even their order remained the same from 2016 to 2017. In terms of absolute numbers, though, the USA took a leap forward (up from 100 award-winners in 2016) and British films received somewhat fewer prizes than in the previous year. Of the total awards presented on the website, around half were received by films from only nine countries.

Among the smaller countries – in terms of population – 2017 was a successful year in particular for films from Switzerland, Belgium, Sweden and Portugal. Sometimes, individual standout films serve to catapult a country up the list for a short time. Poland, for example, made the top ten in 2017 due to the striking success of CIPKA (PUSSY) by Renata Gasiorowska.

Similar effects can also be seen in countries with a higher film production volume. THE RABBIT HUNT by Patrick Bresnan, for instance, drove up the US award statistics.

The prominence of certain countries among the prize-winners reflects not only their short film production volume, but also of course the number of festivals there. As films have better chances of winning awards on their home turf, more festivals in a particular country mean more wins for domestic productions. Examples of this phenomenon are Germany, Spain and the USA, countries with a large number of short film festivals at which home-grown films normally have better chances to win than foreign rivals.

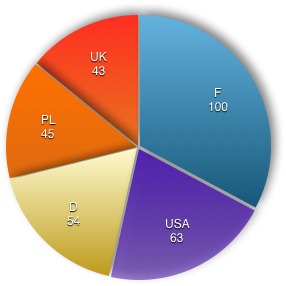

Likewise of interest are the numbers indicating films’ success abroad. Here the following picture takes shape (when co-productions are also counted): enjoying the greatest acclaim in foreign climes in 2017 were films from France (100 awards), the USA (63), Germany (54), the UK (43) and Belgium (30). As in 2016, films from France were once again the most successful internationally. US films did better and those from the UK did worse than before (34 and 65 foreign awards respectively).

Number of films awarded abroad (5 most successful production countries)

Among the countries that do not offer a line-up of short film festivals as strong as those in Germany, France and Spain, a disproportionate success rate was enjoyed in 2017 by the Netherlands, as was also the case in 2016. The films produced there that met with success abroad included GREEN SCREEN GRINGO by Douwe Dijkstra and IMPORT by Ena Sendijarevic.

Success at home vs. recognition abroad

In prior years, films from Italy, Brazil and Spain won substantially more awards at home than abroad. Otherwise, there were no major discrepancies between domestic and foreign success, with the exception of countries without or with very few of their own short film festivals.

For films from Germany, we registered more prizes at home than abroad in 2017. Germany is however a special case in our statistics, because our website lists the awards even at its smaller festivals with little international participation. German short films received 145 awards at home in 2017 (2016: 138) and showed a continued decline abroad, with 54 prizes (2016: 58; 2015: 91). If co-productions (WATU WOTE, D/Kenya) are counted, however, the number rises to 79 awards abroad.

Conversely, films from the Netherlands (with 82% foreign awards) and Poland (76%) were much more successful outside their own countries. This is due in the Netherlands to a relative dearth of short film festivals and in Poland to a one-off effect (the film CIPKA, see below).

The countries without a real short film festival scene whose films receive awards almost exclusively abroad include Russia (100% of prizes received abroad) and China (90.5%).

Germany’s favourite production countries

In Germany, the most decorated films in 2017 came from France (12 awards), the UK (12), Switzerland (8) and the USA (8). This continues a long-term trend: for the third time in a row, French films were the most popular in Germany, followed by British productions. Films from the USA, which had declined in popularity in recent years (with 3 German awards in 2016) showed a resurgence.

Preferences in other countries

French films received the most foreign awards in Germany and Italy (12 each), the USA (7), and Spain and Switzerland (7 each).

British films were particularly successful, as has been the case since 2013, in Germany (12 awards), the USA (6) and France (4). Notable is that German films conversely did not find much favour in the UK, although they did do slightly better than in previous years, with three awards (2016: 1 award).

Films from the USA met with acclaim across a broad range of countries, but received the highest number of awards in the UK (9) and Germany (8).

Spanish films took home the most foreign prizes from France (7) and Italy (4).

Films from the South American countries in turn received the most awards on their own continent, and otherwise appreciable recognition only in Spain.

And productions from the Nordic countries did the best abroad in France (8 awards), Germany (7) and the USA (5).

German films for their part enjoyed the greatest success in 2017 in Spain (7 awards), the USA (6), France and Austria.

International orientation of jury decisions

In Austria, Italy, Japan and Poland, more than half of the winners in 2017 were foreign films. In Germany as well, just over half of all awards were bestowed on foreign productions, in contrast with the pride of place enjoyed in previous years by German films.

As before, more prizes were awarded this past year to domestic than to foreign productions in Spain and the USA.

The widest range of countries represented amongst the winners in competitions and at festivals can be found in Germany (45 different countries) and the USA (34), followed by France (30), Spain and Italy (29 each). This is the same order as in 2015 and 2016 but with the USA and France switching places.

In total, the 2017 award-winners came from 88 different countries. The tendency toward greater internationalization witnessed over the last 10 years is thus stagnating. In 2016, the number of countries was also 88, and in 2015 it was 84.

The year’s most successful films internationally

The most successful short film of 2016 by far was the fiction piece TIMECODE by Juanjo Giménez (ES), which again made it to the top ten in 2017. In 2017, the most awards by a wide margin were received by two very different films that have in common only the fact that they were made at film schools: CIPKA (Pussy) and WATU WOTE (All of Us).

In the animated film CIPKA (Pussy) by Renata Gasiorowska from Poland, a young woman is interrupted so many times while masturbating in the bathtub – for example by a voyeuristic neighbour – that her pussy hops away and, like an escaped pet, has to be caught again for there to be a Happy End. The young director, who did the artwork for the film herself, made it in 2016 during her fifth year of studies at the Lodz Film School PWSFTviT. The film has enjoyed an astounding degree of international exposure. The official website Polish Shorts lists almost 400 festival participations from September 2016 to March 2018, only five of them in Poland. CIPKA took its first award at Lagofest in Italy (Special Mention) and in Germany at the DOK Leipzig in 2016 (Audience Award). According to Polish Shorts, the film has received only a single prize in its home country to date (3rd prize in the student competition O!PLA).

In Germany and France, CIPKA can still be viewed until 1 April 2018 on ARTE online.

Tied for the most awards in 2017 was the German-Kenyan production WATU WOTE (2016/17). The 23-minute fiction film by Katja Benrath (director) is based on real events in Kenya: A coach travelling through the northern part of the country was attacked by members of the Islamist Al Shabaab militia, who demanded at gunpoint that the passengers turn over any Christians among them. But the passengers disguised a Christian woman and thus risked their own lives by refusing to surrender her. Katja Benrath’s final project at the Hamburg Media School, which sends a universal message of brotherly love and religious tolerance, was filmed in Kenya with a Kenyan crew. Among other honours, WATU WOTE won the prize for Best Narrative at the 44th Student Academy Awards in 2017 and was nominated for an Oscar in 2018.

There is also a tie for second place in the 2017 ranking, between the French animated film NEGATIVE SPACE (2015–2017) and THE RABBIT HUNT (USA, 2017), the first documentary to make the top ten.

In only six minutes, the stop-motion animation NEGATIVE SPACE tells the story of a lifelong father and son relationship from the point of view of the son, who remembers his father mainly for his advice on how to efficiently pack a suitcase. The obsession with avoiding wasted, or “negative” space leads to shared activities but also casts a sad light on the relationship.

NEGATIVE SPACE was made by the France-based duo Tiny Inventions, comprising Max Porter from the USA and Ru Kuwahata from Japan. The film was produced by Ikki Films in cooperation with ARTE France. This film, too, can boast an impressively long list of festival screenings. From the second half of 2017 until today, NEGATIVE SPACE has been shown at nearly 100 festivals and has also received awards at many of the smaller festivals whose results do not appear on our pages.

The great attention attracted by the film is surely owing in part to co-producer ARTE France, which posted the film intermittently on Facebook, reported on it and is showing it until 13 June 2018 on its online platform. Moreover, the film is distributed by the very active and dedicated distributor Miyu, which was represented in the 2018 Academy Awards nominations not only by NEGATIVE SPACE but also by the French animated film GARDEN PARTY.

THE RABBIT HUNT (USA 2017) is the first documentary film to make it onto our list since 2012 and has amassed a considerable number of awards. It is an observational documentary by Patrick Bresnan (director) and Ivete Lucas from the Austin Film Society. They have been working together for years in the Florida Everglades on a project about life in the communities on Lake Okeechobee. The short film documents how a young man and his family hunt rabbits using only sticks, following a local tradition. The hunt takes place near a sugar mill on a sugar-cane plantation, where the boys take advantage of how the animals run for cover when the huge harvesters make their way through the fields. The spoils of the hunt are then prepared and eaten in a humble kitchen. In only 12 minutes, the film manages in an astoundingly compact and nuanced manner to address the issues of industrial agriculture and the impoverishment of the predominantly black rural population.

Next in the ranking is an animated film, MIN BÖRDA / THE BURDEN (S, 2017). Director Niki Lindroth von Bahr refers to her work as “a dark musical enacted in a modern market place”. Four episodes show animal figures as workers in a call centre, a fast food restaurant and a supermarket as well as guests in a motel who dance and sing about the burden of loneliness and monotony, dreaming of escaping their meaningless workaday world.

Niki Lindroth von Bahr is an artist and costume designer who has worked for celebrities including David Bowie (BLACKSTAR) and also designed the puppets for the equally successful short film LAS PALMAS (Johannes Nyholm, S, 2011). MIN BÖRDA embarked on its festival career in the Quinzaine des Réalisateurs programme at Cannes and was subsequently screened at many major international festivals. The film recently received the Swedish Film Award (Guldbagge, 2018). It is distributed in Germany by the KurzfilmVerleih Hamburg.

Tied for fourth place on our list are TIMECODE by Juanjo Giménez, the fiction film CHASSE ROYALE and the animated films KÖTÜ KIZ / WICKED GIRL and FIGURY NIEMOZLIWE I INNE HISTORIE II (IMPOSSIBLE FIGURES AND OTHER STORIES II).

CHASSE ROYALE by Lise Akoka & Romane Guéret (F, 2016) already got its start in 2016 in the Quinzaine des Réalisateurs programme at Cannes (Prix du meilleur court métrage) and was nominated for a César in 2017. The coming-of-age film about a young girl who auditions for a film was produced by Raoul Peck’s company Velvet Film.

KÖTÜ KIZ / VILAINE FILLE (F, 2016) by Ayçe Kartal is an animated film on the theme of child abuse. A little girl confined to a hospital bed thinks back on happy holidays in the village with her grandparents, but her thoughts soon turn into nightmares about animals that become increasingly demonic. The website for the production lists participation at nearly 60 international festivals – in this case, mostly animated film festivals.

FIGURY NIEMOZLIWE I INNE HISTORIE II (IMPOSSIBLE FIGURES AND OTHER STORIES II) by Marta Pajak (PL, 2016) resembles CIPKA in its minimalist style (ink on white paper) but incorporates more ornament. The narrative animated film is likewise about a woman in her apartment. After hitting her head on the edge of a table, she experiences a parallel world of perfect illusions. The film has been screened since 2016 at nearly 50 festivals.

The other successful films in 2017 included – once again with the same number of awards – AND SO WE PUT GOLDFISH IN THE POOL by Makoto Nagahisa (fiction, Japan) and, last but not least, two German animated productions: OUR WONDERFUL NATURE – THE COMMON CHAMELEON by Omer Eshed (Lumatic, Berlin 2017) and SOG by Jonatan Schwenk.

Launched in 2016 and still successful

A few films that got their start in 2016 continued their successful festival career in 2017. Top-ranked in both years were the previously mentioned TIMECODE, the Hungarian animated film BALCONY by David Dell’Edera and the Canadian animated film BLIND VAYSHA / VAYSHA, L’AVEUGLE by Theodore Ushev.

German films

Five German films and co-productions were among the 24 films with more than four awards in 2017 (in 2016 there were also 5, and in 2015 there were 9).

Two additional animated films belong to this successful group: the animated documentary KAPUTT by Volker Schlecht & Alexander Lahl featuring the voices of former prisoners of the notorious East German women’s prison Burg Hoheneck, and newcomer Nikita Diakur with the partially crowd-funded computer animation UGLY (Mainz, 2017), which uses puppet animation within dynamic computer simulations.

Audience awards

A total of nearly 185 audience awards were cited on our website. While in past years the audience and the expert juries were of one mind with their choices, in 2017 there were only two overlaps: OUR WONDERFUL NATURE – THE COMMON CHAMELEON and WATU WOTE (ALL OF US) led the list of most popular films.

Next in audience popularity were the satire RED LIGHT (BG/HR, 2016) (https://www.havc.hr/eng/croatian-film/croatian-film-catalogue/red-light-by-toma-waszarow), a fiction film by Toma Waszarow, and the integration comedy OBST & GEMÜSE (Fruit & Vegetables) by Duc Ngo Ngoc (fiction film, Filmuniversität Babelsberg Konrad Wolf, 2017).

A striking trend that runs counter to past years was that the most popular films with the audiences but not the juries were fiction films – and not, as might be expected, animated shorts.

The great majority of audience awards were scattered among a large number of films. 175 of the 185 registered awards went to different films! In 2016, all of the top ten films selected by the juries were also awarded audience prizes. But in 2017, five of the top-ranked films did not receive a single audience award, and only WATU WOTE won a significant number (4).

Film categories

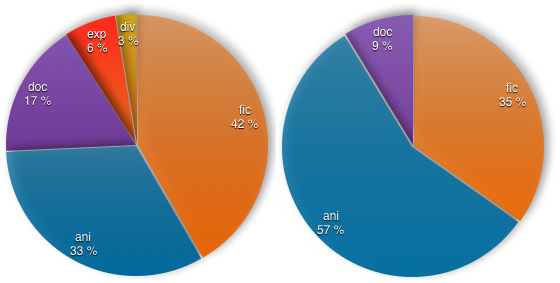

Film categories and genres are admittedly difficult to separate these days when many films have a hybrid character. But we do have some data available, as most festivals still ask those submitting films to choose a category.

With the caveat that we are lacking this information for almost a quarter (400) of the prizes registered on our website, an evaluation of the remainder paints a clear picture: 549 awards for fiction films, 430 for animated films and 220 for documentaries. 34 awards went to “other” (usually music videos). Experimental film, which has become a particularly questionable classification, accounted for 85 prizes.

Distribution after categories (left all, right films with more then 4 awards)

What is difficult to understand is why, among the 24 films with more than four awards, only two are documentaries – not counting the animated documentary KAPUTT. With 13 titles at the top of the ranking, animated films are represented disproportionately. Eight of them are fiction films.

The careers of short films awarded at prestigious feature film festivals

Short films once played only a supporting role at festivals dedicated primarily to feature-length film. At most of the major festivals, however, the short form is in the meantime no longer a mere lead-in but is accorded its own competitions. This means that the short films shown there must be premieres. As festivals are the primary platform for short films, the question is to what extent this eligibility requirement keeps them from being screened elsewhere or else excludes them from enjoying a festival career. General data on the festival fortunes of shorts on the programme at major feature film festivals are not available, but the following analysis shows that films that have met with success at one of these festivals rarely go on to receive honours afterward.

• Sundance (01/2017): The winners of the Grand Jury Prize (AND SO WE PUT GOLDFISH IN THE POOL, see above) and the Award for Animation (KAPUTT, see above) were successful at subsequent festivals, but those in the other categories were not.

• Rotterdam (02/2017): Of the three winners of Tiger Awards, only RUBBER COATED STEEL with its honourable mention gathered further prizes (3 honourable mentions in Winterthur and also at 25fps).

• Berlinale (02/2017): The Golden Bear winner, CIDADE PEQUENA, went on to win an honourable mention in Grimstad (N). The Silver Bear winner, ENSUEÑO EN LA PRADERA received one more award (at Cinequest, San Jose). For STREET OF DEATH (Audi Short Film Award) there were no further wins. The EFA nomination, OS HUMORES ARTIFICIAIS, received a Best Director award at Vila do Conde (P).

• Cannes (05/2017): Only the Palm d’Or winner, A GENTLE NIGHT (China), went on to win further awards (at Limassol and the Chicago International Film Festival). The winners in the other categories did not, with the exception of RETOUR À GENOA CITY (an audience award in Montpellier).

• Locarno (08/2017): Both the Pardino d’oro (ANTÓNIO E CATARINA) and Pardino d’argento (SHMAMA) winners came up empty in the further course of the festival season. Of the two award-winners in the Swiss competition, only REWIND FORWARD won again elsewhere (an honourable mention in Winterthur).

• Venice (09/2017): Only GROS CHAGRIN (Orrizonti Award and EFA nomination) received further honours (in Gijon). As the Venice festival takes place relatively late in the year, we should however mention that, of the previous year’s winners, only the EFA nomination from 2016 went on to win a further award in 2017 (at Animafest Zagreb).

Award concentration in 2017 – it’s still lonely at the top

We already noticed in our first annual awards review (in 2008) that the distribution pyramid for short film prizes tended to taper off considerably toward the top. In 2009, only 15 films managed to amass more than four awards each. The pattern continued in festival year 2010, when 54 films swept up nearly one quarter of all prizes. In 2011, 18 films dominated, with more than four awards each. And in 2012 there were 30 films that pocketed more than four prizes. In 2013, a “top tier” of 42 titles together accumulated more than 253 awards (18 of them more than four prizes each). The top-ranked 53 films in 2014 accounted for a total of 295 of all awards that year (26 of them taking more than four) and 956 films received only one award each. In 2015, 26 films were recognized with more than four awards each, together taking 12% of all of the year’s festival prizes. 26 films again swept up more than four awards each in 2016, accounting for 10.4% of all awards.

In 2017, 24 films received more than four awards each and thus accumulated nearly 170, or some 10% of the prizes registered in total for the year. In other words, 1.9% of all winning films took 10% of the awards. 988 of a total of 1,244 award-winning films received but a single prize in 2017. We can therefore conclude that the distribution pyramid has become somewhat broader at the base, but the peak has at the same time become even narrower.

Reinhard W. Wolf

Postscript: Disclaimer 😉 After we post these annual statistics online, we sometimes receive letters from filmmakers telling us they have received more awards than the ones mentioned here. This is no doubt correct if one takes into account all competitions and festivals worldwide, including smaller regional events. The selection of festivals evaluated here is however limited in terms of quality and quantity. The criteria are openly disclosed in the introduction above. These are the same festivals that are listed in the monthly Festival Calendar on the website. If any important short film festivals are missing there, please let us know!

Links to directors, producers, films online and trailers

CIPKA (Pussy): Polish Shorts

CIPKA (Pussy): Film on ARTE online

WATU WOTE (All of Us): Producer’s website Hamburg Media School

NEGATIVE SPACE: Filmmaker’s website

NEGATIVE SPACE: Film on ARTE online

THE RABBIT HUNT: Official website

THE RABBIT HUNT: Film on Vimeo

MIN BÖRDA (My Burden): Filmmaker’s website with trailer

CHASSE ROYAL: Unifrance

KÖTÜ KIZ / VILAINE FILLE: Producer’s website

FIGURY NIEMOZLIWE I INNE HISTORIE II (IMPOSSIBLE FIGURES AND OTHER STORIES II): Producer’s website with trailer

AND SO WE PUT GOLDFISH IN THE POOL: Film on YouTube

OUR WONDERFUL NATURE – THE COMMON CHAMELEON: Film on Vimeo

KAPUTT: Producer’s website

KAPUTT: Film on New York Times

UGLY: Filmmaker’s website

SOG: Filmmaker’s website

RED LIGHT: Producer’s website