Around the year 2000 the former Big Six, now Big Five after the merger of Disney and Fox, the six big Hollywood film studios, released more than 200 movies a year. In 2018 only a little more than 100 films. Not only the number of films produced has decreased, but also their diversity. Among them were hardly any independent films, hardly any art house films and hardly any films in the medium field of decent entertainment.

Thereby not less money was invested. More and more money has been pumped into blockbuster productions – most money in action and fantasy sequels, franchises and remakes. The result: between 2007 and 2011 alone, the total profits of the Big Six fell by 40 percent. Most sequels of the past few years “bombed,” as the Wall Street Journal wrote. The remake of BEN HUR (MGM), for example, cost $100 million and only earned $11 million in the first week. Today, film studios account for less than 10 percent of the profits of their parent companies.

The ICON – Netflix Headquarters in Los Angeles

Most of Warner Brothers’ large historic studio area on Sunset Boulevard is now occupied by Netflix. The first building, called ICON, was described by the New York Times as the “Townhall of Hollywood”[1]. At the moment one block further EPIC is under construction. Netflix currently rents 100,000m[2] in the greater Los Angeles area – almost all office space!

Nobody could say exactly what Netflix is (and will be tomorrow) today: a technology company, a media company, a film distributor, a film or television studio, a content producer? To this question, Chief Product Officer Greg Peters replied to Vanity Fair: neither a content company or a tech company. Rather, Netflix is an “entertainment company that merely uses technology to tell stories in a more compelling way”[3].

Vanity Fair suspects that this term is a kind of protective claim – similar to Facebook claiming not to be a media company in order not to be subject to the respective ethical and legal standards. As an entertainment or media company, Netflix distances itself from Silicon Valley, which has become synonymous with Big Data and the evaluation of user data – including misuse – through algorithms. In fact, however, this is the foundation of Netflix’s business and the cause of its success. The only difference from the bad guys: Netflix does not sell user data to advertising companies, but uses it itself to control its purchases and, more recently, the production of “original content”. Netflix probably has the most sophisticated analysis tools among all video-on-demand providers. Of course, spying on the preferences and habits of its subscribers only serves the good purpose of being able to better advise customers and give them what they really want.

Short film as a snack

That’s why questions about future priorities and programme content regularly run nowhere in interviews with Netflix creators. Last year, the Frankfurter Rundschau also asked (thankfully): “Will Netflix be making more short stories in the future? Greg Peters replied: “We continue to experiment with different forms. One way we want to pursue, however, is actually shorter stories, more snack-like content. We’ve already done some projects and we’ll see how much people are attracted to it”. The “we will see” certainly refers to the analysis of the feedback from the more than 2000 “key communities” into which the Netflix algorithm has categorized its clientele.

Artificial Intelligence

An example of December 2018 shows what a program looks like when concentrated Artificial Intelligence has been applied to subscribers. The program was packed with buzzword titles such as “Christmas Inheritance”, “El Camino Christmas”, “The Christmas Chronicles”, “A Christmas Prince”, “The Princess Switch” and “A Christmas Prince: The Royal Wedding” [4]. Christmas 2019 will see similar films, including not only Netflix Originals, but also some Disney productions. The latter probably for the last time, because Disney starts its own VoD channel in November and pulls films by Disney and Fox from the Netflix catalogue.

Disney is not the only studio to cancel licenses at Netflix due to new business models. This is one of the main reasons for the change of the company from a film sender (formerly a video store with delivery service) to a film producer.

Netflix films in the cinema

In 2018, Netflix invested a total of $ 8.5 billion (borrowed money) in content and released more than 80 in-house productions. That’s almost as many movies as all the above mentioned studios put together. As a result, Netflix was accepted as a member of the Motion Picture Association of America (MPAA – the club of the Big5/6) at the beginning of this year. At the same time, the company announced that it would increasingly bring its own feature film productions to the cinema before they were offered online.

The current flagship is a new film by Martin Scorcese: “The Irishman” will have its premiere at the New York Film Festival in September and will be released in cinemas starting November 1st. However, this turns out to be difficult. As with “Roma”, the big cinema chains block the release. Instead of the offered 27-day evaluation window, they demand 90 days of cinema evaluation before the film goes online.

Among the 10 other films to be released this year are a new film by Steven Soderbergh, who actually turned his back on the film business, an Eddie Murphy comedy, the first long animated film by Jérémy Clapin (short film “Skizein”), the Cannes prizewinner “Atlantique” by Mati Diop and a bio-pic by Fernando Meirelles about Pope Benedict (Joseph Ratzinger).

The main reason for the cinema activities are the hopes for an Oscar, an Emmy Award and other movie awards. But behind this is also the realization that the cinema audience still has a certain power of opinion and that many VoD users are cinemagoers at the same time.

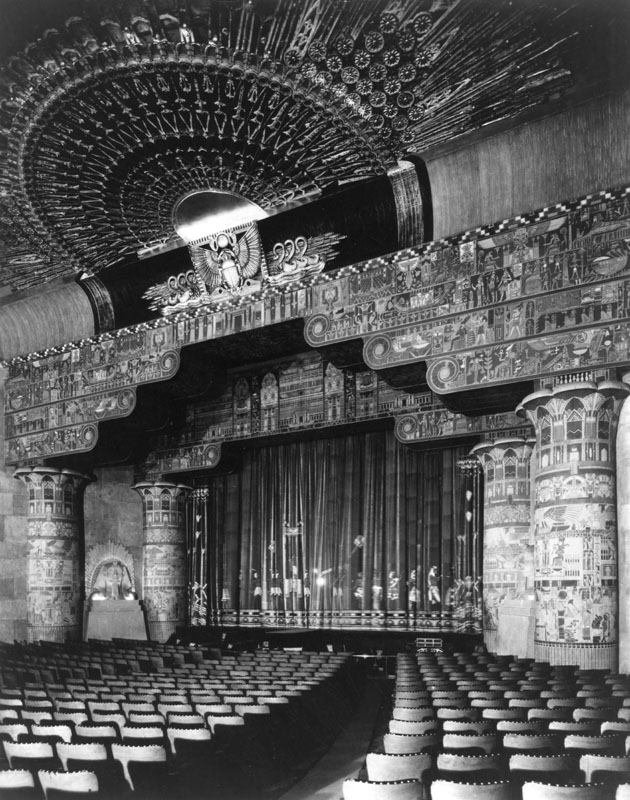

In addition, Netflix learns from traditional film studios that it is advantageous to tie customers back to events and places in real life. It is also fitting that Netflix and the American Cinematheque are pleased to announce the purchase and joint operation of the traditional Egyptian Theater on Hollywood Blvd. In any case, Netflix could be pushed to invest directly in cinemas instead of renting them as before, if the positions of the big cinema chains regarding the evaluation windows remain hard.

MUBI and other streamers also invest in cinema films

Amazon has been producing feature films a little longer than Netflix and founded the film studio Amazon Studios in 2015. Amazon relies on well-known director names and author cinema. The most successful so far has been “Manchester by the Sea”. Among the productions of the last years are Woody Allen’s “Wonder Wheel”, Spike Lee’s “Chi-Raq”, Lynne Ramsay’s “You Were Never Really Here” and the remake “Suspiria”. The latter was shown in only a few cinemas in the USA, but was very successful there.

In the UK “Suspiria” (directed by Luca Guadagnino) was launched in more than 100 cinemas by the VoD provider MUBI. Remarkable that no traditional film distributor was interested! This week MUBI announced that the world rights to Luca Guadagnino’s short film “The Staggering Girl” had been acquired.

In Germany, MUBI is understandably only known as a video-on-demand platform. But in the UK MUBI has been on the cinema market as a film distributor since 2016 (later also in the USA). The distribution catalogue includes “Arabian Nights” by Miguel Gomes” (P/F/D/CH), “On Body and Soul” by Ildikó Enyedi, Ali Abbasis “Border” and Jean-Luc Godard’s “Le Livre d’Image”. This month MUBI shows “Leto” by Kirill Serebrennikov in British cinemas.

MUBI justified this expansion of the original core business with its love of cinema and the experience that the use of films in the cinema has a positive effect on later online demand.[5]

The first film production in which MUBI participated was the transgender love story “Port Authority”. On the occasion of the premiere in Cannes, Efe Çakarel (CEO) announced that MUBI plans to develop another 10 film projects and to participate in the production of two or three films next year.

Cakarel also mentioned that some of the MUBI films were more profitable in the cinema than online …

Convergence

The turn of many streamers towards cinema is already surprising and one would not have guessed it a few years ago. Conversely, traditional companies in the film industry are also changing and integrating streaming services into their business models. So the own VoD service Disney+ will be launched in November with a huge catalogue of in-house productions. First in five countries (USA, CAN, NL, AUS, NZ) [6], then worldwide. Other film studios are already involved in platforms, such as Time Warner with HBO now, or just on the go.

Kevin Mayer (Chairman, Direct-to-Consumer) stellt am 23.8.19 auf der D23 EXPO die VoD-Plattform Disney+ vor – The Ultimate Disney Fan Event (The Walt Disney Company/Image Group LA)

This speaks rather for a convergence of the film, media and technology companies – thus a fusion of Hollywood and Silicon Valley, to put it metaphorically.

This is also evident in the personnel who work or have worked in the respective companies (see also “Jeffrey Katzenberg announces premium short form video platform Quibi”). Film studios are hiring former employees of cable TV broadcasters, streaming platforms are looking for programmers who have gained experience on Google and Facebook, Amazon is hiring film producers and former film producers or cinema operators are founding VoD platforms.

Disruption?

For some VoD platforms, the cinema affinity is immediately apparent when, for example, they structure their offer by cinema model – with curated programs or virtual tickets (see also our article on cooperations with VoD providers).

Statements such as “streaming platforms displace or destroy the cinema”, as they are expressed defensively or affirmatively, depending on one’s point of view, often combined with the buzzword disruptive, are therefore not correct. More and more studies[7] prove that the two forms – the individual consumption of films on small screens and the cultural practice of cinema – do not have to cannibalize each other, but can complement each other.

However, the threat remains that ‘civil’ corporate cultures will expire and unscrupulous representatives of the fast money, which can be earned with big data and algorithms, prevail. In this respect, it is a difference whether you have an owner-managed film studio in front of you or a listed IT company.

As far as the new VoD platforms are concerned, in the near future the consumer will first of all be irritated by the lack of clarity. In addition to the players mentioned above, Apple TV+, Facebook and Instagram are also at the start and Microsoft is developing its XBox as a movie playback platform. Film licenses are changing ownership faster and faster and are being pushed back and forth between platforms and distribution channels. Film lovers will not be able to find their favorite movie so easily in the future, and it will be harder to follow their favorite series than a shell player on the sidewalk.

Reinhard W. Wolf

[1] https://www.nytimes.com/2019/07/14/business/media/netflix-lobby-hollywood.html

[2] https://urbanize.la/post/netflixs-latest-hollywood-building-nears-its-peak

[3] https://www.vanityfair.com/news/2019/03/can-netflix-take-over-the-world-without-turning-evil

[4] https://www.esquire.com/entertainment/movies/g25383267/all-netflix-original-christmas-movies-ranked/

[5] “We’re really committed to the theatrical films that we buy – we encourage our current members to film on the big screen,” said Cakarel. MUBI when it goes online. That’s a key insight. “(…)

“Cinemas are here to stay, we really believe in that experience. At MUBI we are not trying to replace cinema – we want to make films more accessible and convenient.

[6] https://www.thewaltdisneycompany.com/new-global-launch-dates-confirmed-for-disney/

[7] For example, Summary of EY report https://www.natoonline.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/EY-NATO-Report-summary-The-relationship-between-movie-theatre-attendance-and -streaming-behavior-2018-04-26.pdf and ” Cinemagoers 2018″, FFA 2019 , p. 72 and p. 77, PostTrak Report (1.25 million viewers surveyed for 7 years) USA 2019

Photo caption: Entrance door Grauman’s Egyptian Theater, Hollywood Boulevard, Hollywood, Los Angeles, California, USA, Photo: Andreas Praefcke , 2008; Wikimedia Commons

1 Trackback