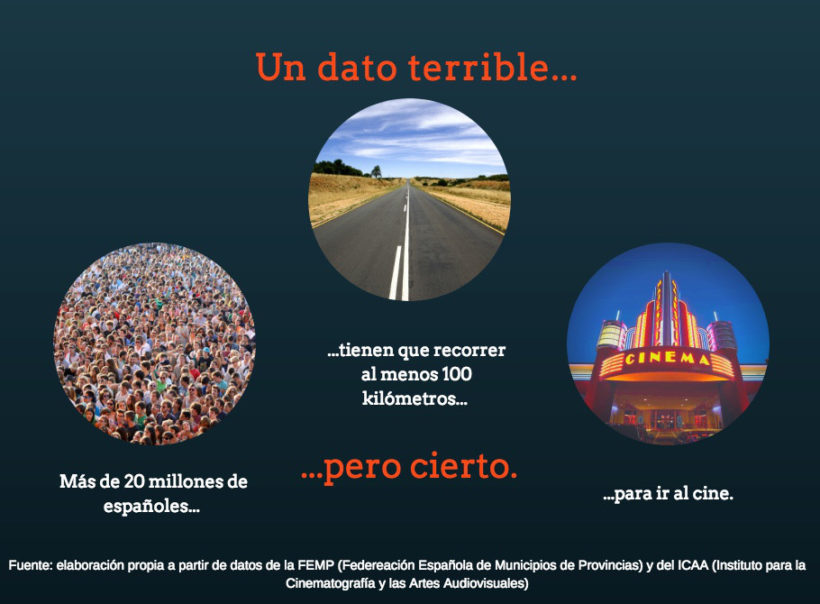

Chart “20 million Spaniards have to travel at least 100 km to go to the cinema.” © film2es

When the new communication technologies – which we generally call social media today – were implemented into mobile phones about 10 years ago, resourceful nerds and cinema-loving fans came up with an idea that everyone thought was great at that time: Link together our local offline world of cinema with the ubiquitous online world of viral communications, and utilise this new media practice to support our endangered cultural practice of cinema-going. Computer applications were written that permitted likeminded fans of films to arrange, with minimal effort, to see together a certain film or even a short film programme at a cinema in their vicinity.

Such initiatives started in many countries between 2012 and 2015, and were referred to as cinema-on-demand or theatre-on-demand. From a content perspective, differentiations occurred in terms of the focus on target groups or communities, as well as with specialising in specific film genres. Most of the platforms cooperated with film distributors, while some of them also established direct contacts with producers and filmmakers, so as to also be able to show movies on cinema screens without any distribution link. The working arrangement with the cinemas, however, always had a similar structure: Once a specific number of cinema-goers showed their interest in a film of their preference, this film would then be screened by the partner cinema on the agreed day. And when this set-up did not succeed within the allotted time, then the screening would simply be cancelled.

This certainly looked like a win-win situation, with benefits for both the film content providers and the movie fans. For the cinemas involved, in addition to the guaranteed income from these screenings, they were also able to fill their empty seats at time slots and on days outside their main screenings when the cinemas were full anyway (which, however, was potentially one of the mistakes made here).

Yet already by the start of 2016, the magazine Celluloid Junkie was reporting that the model had failed everywhere and that most likely forever. The well-known platforms that abandoned their projects or were obliged to do so included Gokino.ch in Switzerland, We Want Cinema in The Netherlands and La 7e Salle in France. Gokino, which was launched by the Pathé Suisse and Cinérive cinema chains, began with fifteen cinema screens in Zurich, before soon expanding its activities to Basel, Bern and Lausanne. Mainstream movies were primarily offered, but no current releases. Yet after a year in business, the results still proved disappointing. There were rarely enough audience members coming to the screenings to cover the costs. And today, the Gokino URL takes you to an erotic website…

La septième salle in France initially focused on film art – and that in a tight timeframe after the cinema release of a movie but before its subsequent release on DVD or VoD. Later on, La 7e Salle also included documentaries and independent films without their own distributors in its programme. By the end of 2012, the platform had more than 80 cinema screens under contract – many of which were in small towns or the countryside (with just two in Paris). This ambitious project failed especially due to people not honouring their reservations – in other words, far too few of the film fans who had registered their interest in seeing a movie actually turned up for the related screenings. And today, all that remains of La 7e Salle is an old Facebook page.

In the Netherlands, We Want Cinema was established as a spin-off of Amstelfilm, a distributor of independent films. We want Cinema even developed its own app for mobile end devices for its crowd ticketing system. Its movie programme primarily consisted of independent film productions. After building up a cinema network in Holland, We Want Cinema even expanded to Germany. In Berlin, Andreas Schaffner from Cinetrans (to cinema operators still known as Filmlager Schaffner) acquired the licence for Germany (wewantcinema.de). With funding from the Medienboard Berlin, he built up a network of almost 30 cinemas in and around Berlin and, doing so, placed his bets – which was perhaps not entirely up-to-date – on so-called cult movies. This project also failed due to low audience numbers.

Today, only a few of the platforms founded at that time are still active. These include Ourscreen (arthouse) in Great Britain, as well as Gathr Films (family movies) and tugg (non-theatrical, educational) in the USA. Interestingly, most of the cinema-on-demand platforms were founded in Australia and Spain, with several of them still in operation. However, the business models in Australia and Spain are also more differentiated than elsewhere. For instance, FILM2 has specialised in the organisation of film screenings in cultural centres and multifunctional auditoriums, because it is pursuing the aim of bringing film art to regions without cinemas (see graph above). VeoBeo is also very widespread geographically, but has a catalogue of just 200 films. It specialises in demanding and sophisticated independent films, and is supported by the Spanish Culture Ministry. However, the newest Spanish platform and at the same time its most successful one is Screenly.

Screenly was established in 2015 by the innovative Love Streams S.L. (“we make responsive cinema”) in Barcelona. Currently, Screenly has 12,000 registered users and shows films on 400 cinema screens. Screenly also works together with film schools and film festivals as “curators”. Its catalogue covers a broad spectrum, from independents to mainstream movies through to film classics. Not only does Screenly target the moviegoers and cinema operators, it also supports filmmakers and producers in distributing their films.

Coming from Australia – and also available in Germany since the autumn of 2018 – is Demand.Film. Its basic idea of using crowd ticketing is identical to all of the cinema-on-demand providers. However, Demand.Film has started with new distribution approaches and the involvement of the potential moviegoers. With the intention being to avoid the mistakes and weaknesses of its failed predecessors. This also includes the strategy of gaining as many “hosts” as possible who act as “inviters” to the film screenings and who themselves organise the bookings. And the platform users who mobilise their circle of friends for a screening, promote a trailer or recommend a film on their social media even get an incentive. For this purpose, Demand.Film has launched its own cryptocurrency, the Screencreds on the NEM blockchain, as a payment system. Not only does the blockchain technology behind it pay out tokens that can be exchanged for cinema tickets, it also registers and calculates the activities and successes of the platform users at the same time.

Beyond Australia, Demand.Film already operates in Great Britain, Ireland Canada, New Zealand and the USA. With its network including 2,500 cinema screens. Its introduction to Germany also represented its market launch on Continental Europe. Here in Germany, its main partner is the CineStar Group, which itself has been part of an Australian group up to now. Genre films and documentaries are the main fare on offer. In a manner similar to Screenly but in a much more pronounced way, Demand.Film focuses on the direct circulation of film titles that have no distributors. This permits time-consuming arrangements and costly film distribution fees to be dispensed with. Cinema-on-demand models like this one eliminate the film distributor player, admittedly by assuming this role themselves. In several pilot projects, Demand.Film is even going one step further and also testing the billing of the film screenings in its own cryptocurrency by means of the blockchain technology, as well as the license payments or the royalties.

For the market launch in Germany, Demand.Film chose the anarchic sci-fi comedy “Schneeflöckchen” (Snowflakes) as its pilot film. The movie was made without any official film funding or participation by a TV station – with just the support from a crowdfunding campaign. Adolfo Kolmerer, its director, producer and actor, commented in an interview that, “The distribution method that Demand.Film uses is a good alternative to the classic film marketing and exploitation models and it’s perfectly suited to niche products like ‘Schneeflöckchen’, as well as for documentaries and low budget films.” (black box 276, 10/2018) It is, however, still too early to assess and evaluate this. “Schneeflöckchen” started in September and is currently available to see on five dates in December, of which admittedly only one screening (in Cologne) has already reached the required minimum audience numbers so far.

The decline in the audience numbers in the cinemas, and especially among the younger age groups, can be traced back primarily – as almost all studies agree – to the increasing acceptance of video-on-demand as an alternative option to watching movies in theatres. For which reason it is easy to see why the marketers of films in cinemas are trying to exploit elements of the on-demand model and the social media communications, together with their user groups, to their own ends. In this way, however, the online sector could perhaps be able to give back something to the cinemas that it has taken away from them. Yet what the cinema-on-demand initiatives that initially failed do demonstrate: The models do not integrate easily with each other. Many of the earlier platforms proved unsuccessful due to quite mundane circumstances, such as for instance misjudging the commitment to actually attend the screenings provided by young people, who come from another culture of fast and noncommittal likes.

A far graver aspect is, however, that almost all of the cinema-on-demand initiatives simply overlook the fact (which is actually surprising for the cinema operators) that cinema and video streaming consist of two entirely different cultural practices. The new media talks in this connection about the user experience. And a successful user experience includes aspects or features that cinema is just not able to provide. In fact, the most important advantages from a user’s perspective is their ability to determine the time and place of the viewing experience and that what they see is individually personalised. Streaming videos can be consumed individually at all times, everywhere and on the user’s own end device – without any external arrangements or the like. And this is something that cinemas cannot do, nor do they want to. Yet differentiations are not only found in the forms of reception. Likewise, there are differences in the content preferred, even if they are not so clear. Shorter formats are more likely to be chosen on VoD channels compared to the typical full-length feature films screened in the cinemas. And currently the series format is proving to be the most popular streaming product, which hardly seems feasible to fill a cinema screening programme.

However in one point at least, the advantage consumers of online media enjoy in terms of the freedom of the time and place they have to consume content has to be critically questioned – and that is when they make their viewing selection from a far broader range of media products. Because, at the same time this advantage is undermined by the same social media strategies that inevitably produce echo chambers and filter bubbles with their rankings and recommendations or, in other words, limit yet again the number of products actually perceived to be available.

Cinema-on-demand initiatives have already experienced this to the extent that the movies demanded from them ultimately reflect the trends at the cinema box offices. And in order to market and screen ambitious non-mainstream “niche productions”, which are positioned beyond our public, media-driven perceptions, more has to be done than merely putting them in an online catalogue. If it is willing to use its potential, your local cinema around the corner does has a competitive edge here to the extent that its cinema audiences trust its operator and are also willing to view films from unknown authors that are not pushed and promoted on all the media channels.

Some of the social media advantages accompanying cinema-on-demand systems can, however, be harnessed productively: The power of networking that should not be underestimated and which reaches the long tail of those interested in specific themes and film genres far more effectively– also within the environment of the cinema concerned. Likewise, the host model is capable of providing opportunities. For instance, hosts from NGOs, local associations, civil society or subcultural groups can avail of their insider contacts to issue invitations to screenings that would not be held otherwise.

One tempting aspect with the model is, of course, that only low financial risks have to be incurred with it. Because films or screenings for which there is no demand are simply not held. In this way, when a screening event does not succeed, the cinemas does not pay any movie rental fees and has either no or only minimal personnel costs to cover. Even the film fan who reserves a seat only pays when the screening actually happens.

And for all those filmmakers and movie content providers who have no chance on the traditional film and cinema market – because they are independent producers or even curators of short film programmes – cinema-on-demand is at least worth considering.

Links:

FanForce (AUS)

Film2 (ES)

Gathr Films (USA)

I like cinema (F)

ourscreen (UK)

Rain Network (BR)

Screenly (ES)

tugg (USA)

We Want Cinema (NL, farewell page) / PowerPointSlide Pitch 2012

VeoBeo (ES)