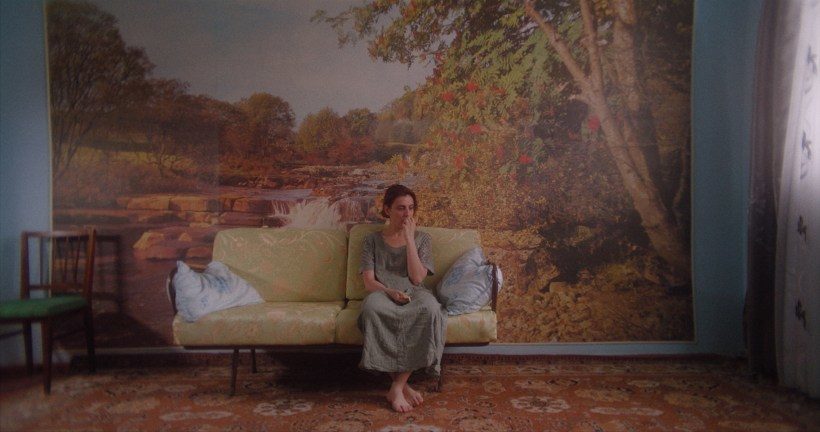

WORLD (USA/Armenia, 2020) © Christine Haroutounian

The short film form, a synonym for certain artistic freedom in the presumptively dependent on high budgets film industry, could play a crucial part in the process of reinvention of a national cinema. The ingenuity and aesthetic diversity of the newest Armenian short films caught my eye still in 2021 when I first attended Yerevan’s Golden Apricot International Film Festival. Its Apricot Stone competition for short films offers a good opportunity for local cinema to present itself within an international environment but also in its original cultural context – since the geographic framework of the section is regional, next to titles from the Caucasus and the Middle East, a substantial number of Armenian films are being showcased as well.

Meanwhile, Golden Apricot unobtrusively but firmly positions itself as the leading film event in the Caucasus – not only with its strong GAIFF Pro industry program line-up, providing chances for projects from the area to find adequate development support and financing but also through its film program, for which the promotion of regional production is of primary importance, as confirmed by the artistic director Karen Avetisyan in an interview for Cineuropa[1]. In his view, it is still early to talk about “new Armenian cinema” as a distinctive stylistic movement, however, certain institutional strategies might help its emergence – there is a plan for launching an international school in Yerevan, based on the concept of the Moscow School of New Cinema founded by the Georgian filmmaker Dmitry Mamuliya according to whom every country has its own “demons of cinema”, the search for which forms and creates a new cinema.[2] Almost all the shorts in this section represent the upcoming generation, not just because short cinema is presumably made by newcomers, but also because the “cinematic thinking” in Armenia today is generated almost exclusively by prominent filmmakers, Avetisyan explains for the Bulgarian Kino Magazine[3]. And further he adds, “It’s hard to talk about a new wave, but it’s definitely the beginning of something turbulent and bright that is still to come. It’s not all about affordable funding for those who are now entering cinema; the real key is to be able to hear their voices.”

For an external viewer like myself, the visual aura of the Armenian shorts is distinctive and powerfully present, just like in the local rich fine arts heritage or in the sharpened recognizable face features of literally every Armenian. This cinematic abundance draws a multifaceted and authentic portrait of contemporary Armenian society through poeticism – narrative and visual. The poetic film language, rooted in Sergey Paradjanov’s exceptional oeuvre which is considered a national treasure, is an identifying and uniting code for Armenian shorts, whether they tackle the painful war subject, social turbulences, or reveal the individual vicissitudes of someone’s private world. Another common feature is their mature content, regardless of the age of the authors, which makes an especially strong impression against the backdrop of Western European short cinema, which, often “spoiled” by funds and training programs, in many cases plays predominantly with the form while neglecting the content.

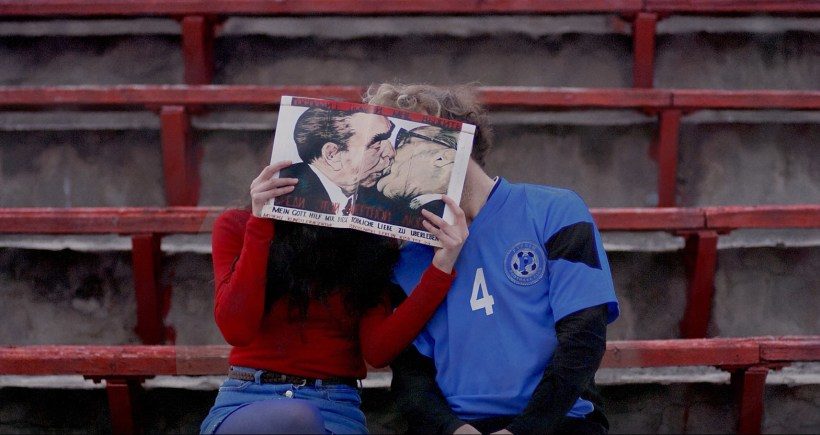

STORGETNYA (France/Armenia, 2021) © Hovig Hagopian

Back in 2021 nine Armenian films took part in the Apricot Stone competition, and two of them deservedly won the main awards: the Golden Apricot trophy for best film went to the USA-Armenian co-production World by Christine Haroutounian, which intimately depicts the controversial emotions, experienced by a young woman caring for her bedridden mother in a desolate village; while the Silver Apricot for directing was handed to the documentary Storgetnya by Hovig Hagopian, a documentary observation of the quiet daily life in a speleological therapy center built 230 meters underground in the Aran salt mine near Yerevan. Both filmmakers come from the Armenian diasporas in the United States and France respectively thus representing the seven million Armenians living abroad against the background of the barely three million population of today’s Armenia.

ORPHANHOOD (Armenia, 2022) © Ovsanna Gevorgyan

In 2022 the Armenian titles in the section are seven and none of them was given a prize, however, they further enrich the local cinematic texture with originality and imagination. Probably the boldest example in this sense is Ovsanna Gevorgyan’s Orphanhood, a phantasmagoric tale on the edge between dream and reality where a scientist manages to bring to life his nightmares. What fascinates in its visual style is the contradictory combination between sci-fi plot and vintage aesthetics, bringing together Soviet “futuristic” infrastructural facilities, retro furnishing in the interiors, traditional embroidery in the costumes etc. Nostalgic, highly allegorical, and prophetic in its anguish, Orphanhood is a softened version of an apocalyptic dystopia, delivered with a quaint approach.

NEXT STATION PARADISE (Armenia, 2021) © Harut Makyan

Another extravagant work is the black-humored dramedy in eight parts Next Station Paradise by Harut Makyan about a young poet and his eccentric entourage who are strolling the decaying cityscape of a provincial ghost-town in an attempt to find a place under the sun and resist the constant harassment coming from their surroundings. Instead of openly mourning the social isolation to which sensitive souls are doomed in a profane and tainted with post-Soviet despair environment, Makyan prefers to create an absurdist world in which sad situations take the shape of a surreal postmodern ballad.

A LONELY NIGHT (France/Armenia, 2021) © Arnaud Khayadjanian

Arnaud Khayadjanian’s A Lonely Night also avoids addressing issues directly, hence it touches upon the ongoing military conflict in Armenia topic from afar – the protagonist gets obsessed with his plants in order to forget his time as a soldier in the Nagorno-Karabakh war but we learn this from in between the lines, via a midnight conversation with his sister, held in mystic light amidst enchanting greenery.

COREAN DELICACY (Armenia, 2022) © Hambardzum Hambardzumyan

Meanwhile, through repulsive realism, Hambardzum Hambardzumyan’s Korean Delicacy tells an anecdotal story of mundane cruelness – a boy’s dog becomes a victim of a horrific joke, made up by his father and a buddy out of mere boredom, again in a remote countryside area. Despite the straightforwardness of the narrative, the plot itself is one more time absurdist, ambiguous, and uneasy to get a hold of.

EMMA (Armenia, 2022) © Martin Matevosyan

Three Armenian shorts are transmitting the female gaze without insisting on being feminist in the political sense. Martin Matevosyan’s Emma is rather forthright in its depiction of a suffocating family atmosphere that restrains female freedom thus getting to grips with the topic of domestic violence.

CROSSING THE BLUE (Armenia/Netherlands/USA, 2022) © Victoria Aleksanyan

The apparently common issue in Armenian society is taken forward in a more subtle way in Crossing the Blue where the protagonist has defeated authorities in order to flee with her child from a husband’s abuse across the Atlantic. However, the topics in focus are more existential: the deportation of Armenian emigrees back home, a suicidal hesitation and the complex mother-son relationship excellently embodied by the expressive dramatic face of Armine Anda in the central role of a mother on the verge between desperation and personal catharsis.

WHEN I AM SAD (Armenia, 2021) © Lilit Altunyan

She transfers those controversial emotions and canalizes them in the more universal image of sadness in the purely poetic, genuinely personal, and gentle piece from the selection, the haiku-like drawn animation When I am Sad, directed by Lilit Altunyan and based on her poem, while co-written and voiced over by Anda herself. Trembling after the intimate frequencies of the feeling of sadness and volatile moods, a girl’s face together with the nature around her metamorphose into different forms, manifested through sighs, spontaneously shared thoughts, and varying physical states. Developing an ascetic but abounding in its means of expression graphic style which organically collides with cinematic language, When I am Sad is among the internationally successful new Armenian shorts not by coincidence, being selected by top festivals such as Clermont-Ferrand, Oberhausen, Animafest Zagreb.

An optimistic wrap-up of this brief story about a little-known cinema with great potential is probably the recent announcement of the newly accepted Law on Cinematography in Armenia[4] which promises local producers non-refundable support – a huge step ahead compared to the currently existing system which requires reimbursement of the funding received from revenues with the same percentage as invested by the government which could reach numbers as high as 40-50%. The law should be adopted within a year, which is a promising signal that more inspiring plots and individual voices from Armenia are expected in the near future – the dominating unification in the globalized film world is yet to make us value their daring uniqueness.

[1] https://cineuropa.org/en/interview/427554/

[2] Ibid

[3] http://spisaniekino.com/archive-kino/spisaniekino-januari-2022/златната-кайсия-2021-рестарт-за-арменското-кино.html

[4] http://parliament.am/legislation.php?sel=show&ID=7743&lang=arm&fbclid=IwAR2fWnvl698AFntS-Ui8abISxVY1bPTAN_GVyFEG1xfPcDxM0tHBIgdjon8#1

1 Trackback