THE BEST OF BOTH WORLDS – Bjørn Melhus doesn’t want to be forced to decide between Black Box and White Cube

Bjørn Melhus is one of Germany’s best-known short-film makers and media artists, and one of the select few whose work has been greeted with interest and acclaim at both short-film festivals and on the arts scene.

In his short films and installations he casts a critical gaze on themes, figures and perceptual patterns that have been launched, and continue to be dominated, by the mass media. Many of his works call into question what at first glance seem to be well-established relationships between medium and viewer, focusing on popular figures and themes from film and television and exaggerating them to the point of deconstruction.

Melhus studied film and video with Birgit Hein1 at Braunschweig University of Art, already experiencing the matter-of-course association between fine arts and film in the first years of his studies. Since 2003, Melhus has held the post of Professor of Fine Arts/Virtual Reality at the School of Art and Design Kassel. He still defines himself today more as a maker of films and videos than as a fine artist.

When I had to, I used to sometimes choose the title of film- or videomaker rather than artist. That may sound pragmatic, but my background is simply in film, and compared to the conventional idea of art, there are some major differences – in the production method, the contexts, the way it is presented, the distribution conditions and above all in the environment for the work itself and the way it is treated.2

Bjørn Melhus’s films and videos are shown regularly at film and media art festivals such as the International Short Film Festival Oberhausen, the European Media Art Festival Osnabrück, the IMPAKT Festival in Utrecht and the Transmediale Berlin.

In recent years, his artistic work has also been featured at the Tate Modern in London, the Museum of Modern Art in New York, the Serpentine Gallery London, the Sprengel Museum in Hanover, the Museum Ludwig in Cologne, the ZKM Karlsruhe and Centre Pompidou in Paris.

Through the magic looking glass – Films about the fascination of television

Born in 1966, Melhus was part of the first generation to grow up with the mass medium of television and to have daily contact with characters from TV series and movies. He claims to have been moulded mostly by American films and series (such as Flipper, Fury and Lassie), even though he today reacts to the characters in these stories with very ambivalent feelings and a mixture of fascination and disgust.3

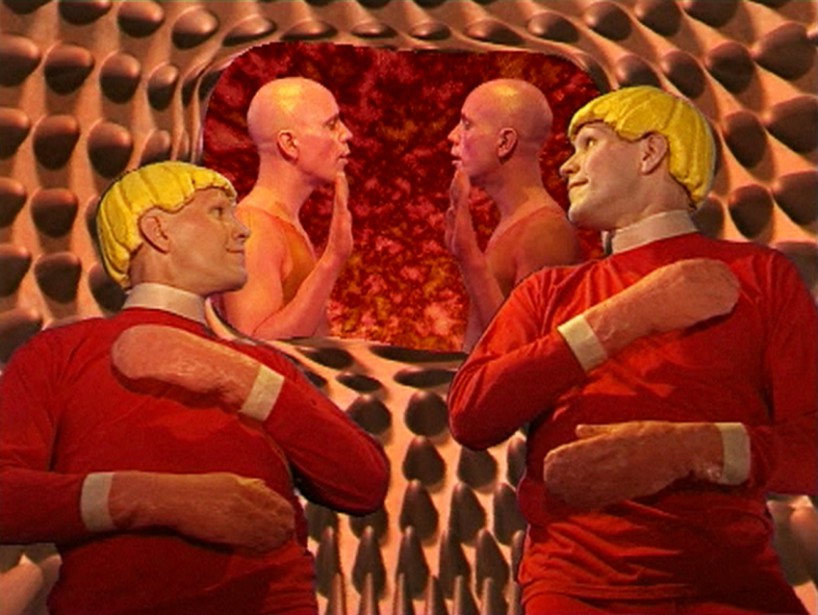

His works frequently reflect the way in which the mass spread of television created a virtual media reality alongside the quotidian one – one that offered striking imagery and many new figures for viewers to identify with. Melhus has by now gathered together in his works a whole pantheon of figures seemingly derived from the audiovisual legacy of America which frequently reappear in various films. His pieces cryptically interrogate the ways in which the mass media play on our entire range of emotions, able to strike entirely new chords. While in the first ten years of his career dazzling TV protagonists were at the centre of his artistic explorations, since about 2000 he has been concentrating more on the structures and rhythms of the medium itself.

The 39-minute film he made while still studying, WEIT, WEIT WEG (FAR FAR AWAY 1997), is often regarded as the key work in this first phase of his artistic career. It is one of his longest and most complex efforts, introducing a cast of characters and a range of themes that would dominate his endeavours until the end of the 1990s.4

Melhus inaugurates a method here that has today become one of his most significant hallmarks: he plays all the roles himself. This is an important, if not the most important, part of his artistic concept, which is based on a radically subjective approach to filmmaking. Melhus does not by any means see himself as an actor, but rather tries with his characters to embody various aspects of his own personality. He cites the main character of Dorothy in FAR FAR AWAY as his most important, intimate and personal role to date. The story is oriented around the movie version of THE WIZARD OF OZ, with Judy Garland starring in the role of the Dorothy, a little girl who is catapulted by a cyclone into a fairy-tale land peopled by both good and evil figures, where she immediately begins to search for the way back home. Melhus himself sees FAR FAR AWAY as a film about “origins, about the question of leaving home, going somewhere else and changing as a person, and about longings.” 5

Sporting braids, a big lime-green bow and matching overalls, he portrays Dorothy by “speaking with her voice”. Melhus uses audio found footage taken from a wide variety of sources – in this case primarily the movie with Judy Garland – first assembling the soundtrack and then shooting scenes and lip-synching to fit it. Both his constant presence as protagonist and the idiosyncratic sound editing are still today distinctive features of his works.

The balancing act between film festivals and the art context

Like a number of other filmmakers and artists who rose to fame on the film festival circuit (such as Corinna Schnitt, Matthias Müller and Christoph Girardet), Bjørn Melhus has turned his attention to the arts scene during the past 5-10 years and begun presenting his works not only at film and media art festivals but also at museums.

Art institutions have long since opened their doors to the moving image. The continual development of video technology has made it easier for museums and art galleries to incorporate works on film and video into their exhibitions. Despite technical advances, however, the conditions under which the moving image is presented in the exhibition space are not always satisfactory. On the contrary: the simplified handling of the technology has in many cases not led to an improvement in projection conditions but rather to a certain negligence of the specific demands placed on the space, and on the curators, by the projection of film and video images.7

In an interview I conducted with Bjørn Melhus on the phone on 22 March, he criticized that works on film and video are still frequently presented under utterly inadequate conditions in galleries and museums.

At some exhibitions you have to wonder what the idea is. Three videos are for example projected onto the wall one after the other, in a brightly lit room. Each video is over one hour long; there is an old wooden chair placed in front, and opposite stands a monitor that belongs to a different work and from which sound constantly blares. That’s just for the birds. The only thing they’re interested in is to say: we have these three films in the show as well. So it’s all about labelling and name-dropping. It sometimes seems to me as though viewers aren’t even meant to really watch the works.

Despite such severe problems with presentation in some cases, the affinity of film and video works with the art context is still unshakeable. Melhus describes two chief reasons for this convergence – ones that certainly do not apply to him alone, but can also be said to describe a general tendency.

The freedom of art – The White Cube enables formal and formative diversity

Working with the exhibition space in mind enables the artist to develop entirely different forms and formats for his ideas. The loop has been essential to many of Melhus’s works from the very start, representing much more to him than merely a technique with which to present a video in the exhibition context without pause. In works such as NO SUNSHINE (1997), the loop also takes on a narrative function and is hence indispensable – which leads to certain problems when the work is presented in the classic cinema context.

In the beginning, Melhus frequently produced two versions of a new work, but today he usually decides against trying to work within both the White Cube and the Black Box, producing instead different works for the respective purposes. Even today, however, all of his works – even those that are already far removed from the classic film narrative – demonstrate with their excessive use of film and television footage that the moving picture serves him as motivation, source material and theme alike.

This focus comes to the fore in exemplary fashion in his installation PRIMETIME (2001), in which Melhus looks at the phenomenon of television talk shows. In this large-scale installation, which extended across two large spaces in its first showing at the Kunstverein in Hanover, viewers first enter a room with a tower of five television sets and are then led along a show stairway that cascades down as if onto a stage into the central room with 29 TV monitors distributed across the walls. The monitors do not show any video or film images, however, but rather illuminate the room with stroboscopically flickering light, which changes in colour, brightness and rhythm in synch with the soundtrack. It becomes evident here that the monitors no longer serve Bjørn Melhus merely as playback devices for video recordings, but have long since themselves become part of the sculpture. The rooms are set up to form a stage on which the viewer becomes part of the talk show, able to immerse himself in the cascade of sound, light and video images appearing on the monitors hanging on the opposite wall.

With this type of sculptural work in space, Melhus had now moved far beyond his origins as film and video artist, willingly adopting the possibilities offered by gallery and museum exhibition. He nevertheless continued to work in parallel on further single-channel videos, such as THE MEADOW and THE CASTLE (both from 2008), which, although developed for the gallery context, also function as short films at the cinema and are occasionally screened there.

In MURPHY (2008), a film of only 3.5 minutes in length that makes do without any classic moving images, Melhus works exclusively with colour video images and his typical audio found footage to address the theme of war in film. The jury at the International Short Film Festival Oberhausen selected this work for its Prize of the Cinema Jury in 2009, attesting that, even without moving images, Melhus had been able to extract the essence of war and action films in his work. In justifying their selection they remarked that, thanks to skilful montage, “the viewer who lets himself in for this cinematic adventure” is able to experience as if first-hand action-packed scenes in which he “slowly rises into the air in a helicopter, is shaken up through and through, and finally lands gently back in his cinema chair”8.

Financing options

It is not without a certain irony that, of all videos, one like MURPHY would receive the Prize of the Cinema Jury at the International Short Film Festival Oberhausen, because it is highly unlikely that it will ever be shown on the big screen. Experimental short films hardly ever find their way into German cinemas. When they do, then it’s at the most as part of a short-film reel, but this is hardly a financial boon to the filmmaker, as Bjørn Melhus recounted to me with a touch of gallows humour:

Up to the end of the 1990s, I acted almost exclusively in the festival context and worked with video distributors. In those days they sometimes pressed 20 DM into my hand as rental fee when my films were screened, sometimes even 30 or 50 DM. That’s just the way it is …I realized back then that you can’t get rich making video art. (…) If I hadn’t done some other jobs during the first 10 years of my career and earned some money renovating apartments, all of it wouldn’t have been possible.

Without grants, promotional funding, teaching posts, and odd jobs it has always been, and still is, impossible to make enough money with film and video art in the festival context to rise beyond the status of self-exploitation.

When it comes to artistic films and videos, the art context offers filmmakers much better financing options9 than the film world – i.e. festivals and film and video distribution – has ever been able to. Added to this is the advantage that the exhibition space furnishes multimedia artists a much greater variety of ways to unfold their creativity because the paradigms of presentation are much more open than in the Black Box with its fixed standards. This advantage is reversed in some cases however due to a lack of sensitivity and expertise with respect to the moving image.

Bjørn Melhus emphasized in our talk that he doesn’t think much of trying to make up for these shortcomings by establishing equally entrenched standards for presenting moving images in the exhibition space. Instead, he pleads for greater sensitivity toward the exigencies of the individual work.

He basically advocates utilizing the qualities of the White Cube as exhibition space and not trying to transform it into a Black Box through structural or technical manipulations. Particularly in the case of longer, narrative works, Melhus believes that there is hardly any way to present them in the White Cube that would do justice to their special requirements. For shorter, single-channel works, he cites – along with obvious basics such as a good, powerful projector, a room that is darkened as much as possible and good seating options – a good acoustic separation from other works and a clear display that indicates how long the projection takes and when the next showing begins.10

“Narrative films in the White Cube make for a strange viewing experience. (…) After all, when I read a book, I don’t start in the middle!”

Despite the advantages of the art context described above, Melhus (and others) adhere to a policy of continuing to show their works in the festival context where they and their careers got started. There are two good reasons for pursuing this strategy as well.

The limitation of the gaze and the lack of discourse

With the development of digital photography and video technology, Walter Benjamin’s “Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction” has been realized much more fully than he could have imagined back in 1935. In no time at all, with just a click, a digital video film can be duplicated hundreds of times; and on the internet reproduction knows no bounds.

But the art market is based on dealing in unique pieces.

Thus, in order to sell digital video productions on the art market, artists and galleries take recourse to the idea of the edition, to the artificial limitation of the number of copies that can be made of a work, similarly to what is practiced in the field of photography.

Bjørn Melhus, who has been represented by various galleries since the late 1990s, now limits his installations to 3 to 5 copies, which are sold to collectors and museums. He always reserves the right to produce an artist’s copy that he can himself lend out and show, a practice that is customary with art installations.

Much more problematic for Melhus is how to limit the reproduction of single-channel video works, which in purely formal terms can be shown in any space, in other words: which do not require any special environment. Here he quickly experienced after his entry into the art market a paradoxical situation in which museums and collections were prepared to pay much more for a work if its reproduction could be artificially limited.

“There is a desire to have something others don’t have. It’s an economy of its own; that’s how the whole art market works. (…) A myth is built up based on limitation.”

The way the art market works is in some ways diametrically opposed to the festival mindset. While on the festival circuit, the value of a film is directly related to how frequently it’s shown; the logic of the art market commands that films lose value the more they are spread around. To raise the price of a work, the audience must therefore be kept as small (and exclusive) as possible.

Melhus laments that this forced exclusivity gives rise to unintended side effects that may even damage the further development of the art, because, for example, the new generation of artists don’t even know what is already out there.

At the same time, limiting the accessibility of artistic film and video works and the resulting restrictions on their exposure hinders any halfway public discourse. This presents a problem for art historians, “who no longer have the opportunity to view artistic works on film and video in the course of their research because they are locked away in a cellar somewhere and are only allowed to be screened every 5 years or so. Art history is hence increasingly being written like in the game of Chinese whispers, based on hearsay alone, and that is a major stumbling block.”

Contemporary art criticism likewise suffers from the lack of a base of experience on which to judge such works or to compare them. This lack of engagement with the works is what Melhus views as the most serious downside in comparison with the film world.

“The contemporary art scene has deteriorated into a fairground where all that counts is which names are being shown in which institution and who then offers which works for how much money in which gallery. Hardly anyone talks about the subject itself anymore, about the art, and that is truly unfortunate.”

Bjørn Melhus is of course aware of how problematic it is to criticize a phenomenon of which he himself is a part. His strategy for countering the trend toward exclusivity and the resulting threat to the discourse is to consistently hold fast to both mainstays: film festivals and the art context.

To his mind, certain film and media art festivals are among the few places “where people still talk about the work at all”. This is one of the major advantages of festivals compared to the arts scene, he says, and one that must by all means be preserved.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, we can say that, for artists like Bjørn Melhus, the two systems of the Black Box and White Cube complement one another in a relatively meaningful way. Those who, like him, have access to both spheres are in many cases in a position to finance their artistic work on film and to compensate for the drawbacks of the art context – such as limited visibility, less-than-ideal presentation conditions and the lack of discourse – through continued engagement with the festival context. In the long run, however, the constant struggle to straddle both spheres would not appear to be expedient for the further development of film and video art.

Melhus demonstrates one possibility for creating a platform for his works while still limiting their exposure with his website www.melhus.de. Excerpts from his films and videos, and video documentaries of his installations, can be viewed here that provide a very good impression of his work. In the “private view” section, for which users first have to request a password (allowing his staff to control who gains access and for what purpose) the works can be viewed in full.

This approach might form part of a potential strategy for tackling and minimizing the problems described above caused by the coexistence of the Black Box, as code phrase for cinematic release of films and videos in the festival context, and the White Cube, referring to museums, galleries and the art market. In the final analysis, the biggest problem is still the divergent logic governing the two different forms of utilization:

In the art context the chief concern is the idea of an original work of art and its exclusivity, while in the festival context the aim is to achieve the greatest possible reach and to foster discourse with other works and artists. It is difficult to reconcile these two strategies – but it is not impossible. The future, and the abundance of ideas brought to bear by all those artists who, like Bjørn Melhus, deal every day with the balancing act between the two worlds, will show whether the opposing spheres can learn something from each other and successfully rise to the challenge.

Links

www.melhus.de

Film between Black Box and White Cube, Reinhard W. Wolf: http://www.shortfilm.de/de/das-kurzfilmmagazin/archiv/themen/film-zwischen-black-box-und-white-cube-teil-1.html

See also the essays on the topic of “Film & Art” by Stefanie Schulte Strathaus (Arsenal, Berlin) and Michael Mazière (London) in the Guest Contributions section (in German only).

Films, videos and installations by Bjørn Melhus

Hecho en Mexico, 2009, (Video, 4 min., loop)

Mars Recovery, 2009, (Installation, Mixed Media)

Scenery Mars, 2009, (Video loop)

Critical System Alert, 2009 (12 channel video installation)

Beagle III, 2009 (video installation for 3 TVs)

Deadly Storms, 2008 (3 channel installation) 7 min. loop

Still Men Out There, 2008 (6 channel installation) 10 min. loop

Tree House # 2, 2008 (video installation for tree)

O-Man, 2008 (Video loop)

Murphy, 2008 (Video) 4 min.

The City, 2007 (Video installation, variable, ongoing project)

99 Floors, 2007 (Video) 4 min.

The Castle, 2007 (Video) 24 min.

The Meadow, 2007 (Video) 28 min.

Captain, 2005 (2 channel installation) 14 min. loop

Eastern Western Park, 2005 (6 channel video installation)

Happy Rebirth, 2004 (Video) 2 min.

Auto Center Drive, 2002 (16 mm Film) 28 min.

Die umgekehrte Rüstung, 2002 (Video) 24 min., loop

Sometimes (Fire in Zero Gravity), 2002 (5 channel video installation) 8 min., loop

Weeping, 2001 (Video projection in 2 canvases) 7 min., loop

Primetime, 2001 (3 channel installation on 29 consumer TVs) 11 min. loop

The Oral Thing, 2001 (Video) 8 min. loop

Transitions, 2001 (3 channel video installation) 4 min.

Good Morning New World, 2000 (Video) 58 min.

Silver City I (Silvercity ist Weit, Weit Weg), 1999 (Video installation) 7 min.

Silver City II (The End of the Beginning), 1999 (Video installation) 7 min.

Again and Again, 1998 (Installation for 8 monitors) 6 min.

Departure Arrival, 1998 (Video installation) 7 min., loop

Blue Moon, 1997 (Video) 4 min., loop

No Sunshine, 1997 (Video) 6 min., loop

Out of the Blue, 1997 (Video) 4 min.

Epreskert, 1996 (Installation and Video) 4 min.

Home 1, 1996 (Video sculpture) 8 min., loop

Weit Weit Weg, 1995 (16mm Film auf Video) 39 min.

OdEssay Video Mail, 1994 (Video installation)

Jetzt (Now), 1993 (Video) 5 min.

Reinigungskassette, 1993 (Video) 60 min.

Das Zauberglas, 1991 (Video) 6 min.

Ich weiß nicht, wer das ist, 1991 (Video) 3 min.

America Sells, 1990 (Video) 7 min

Nicht werfen!, 1988 (Video installation) 16 min.

Cornflakes, 1987 (16 mm Film) 2 min.

Toast, 1986 (16 mm Film) 1 min.

1 Birgit Hein exercised a formative influence on Germany’s film underground in the 1960s and 70s in her roles as filmmaker, curator and author. She herself has been bestriding the conflicting fields of film and art for more than 40 years in her work on film and in particular her activities as curator (e.g. for documenta 6), and she frequently points out that the question of how to show films in the art context has still not been resolved satisfactorily, because adequate standards for presenting works on film and video in exhibition spaces have yet to be established. (Birgit Hein in: Wähner, Christin: “Experimentalfilmprogramme in der 60er und 70er Jahren”, in: Klippel, Heike (ed.): The Art of Programming. Film, Programm und Kontext, Münster 2008, pp. 104-118).

2 Bjørn Melhus in: “Das scheinbar Leichte und Unterhaltsame ist ein Trojanisches Pferd”, interview with Wulf Herzogenrath in: Herzgogenrath, Wulf, Buschhoff, Anne: Bjørn Melhus, Katalog 2002, p. 8.

3 See “Same, Same but Different oder: Die Suche nach dem Eigenen Ich ist eine Unmöglichkeit”, interview with Ulrike Lehmann, in: Kunstforum International, Vol. 167, 11/12 2003, p. 229.

4 The film refers back to many figures and images already introduced in earlier films, e.g. the communication between two characters via television (like in THE MAGIC GLASS 1991) and also inaugurates protagonists who continue to appear in the artist’s works today, e.g. Dorothy (in THE MEADOW 1997 and AUTO CENTER DRIVE 2002). Themes are also addressed that are revisited in later works, such as the duplication of the self, which is found in several instances, in particular AGAIN AND AGAIN 1998.

5 And which he had already tried out in THE MAGIC GLASS 1991.

6 Bjørn Melhus in an interview with Ulrike Lehmann: “Same, Same but Different oder: Die Suche nach dem Eigenen Ich ist eine Unmöglichkeit,” in: Kunstforum, Vol. 167, 11/12 2003, p. 236.

7 It’s worth comparing this statement with a text by Lars Henrik Gass, director of the International Short Film Festival Oberhausen, who says: “As much as we may welcome the fact that these filmmakers [such as Kenneth Anger, Bruce Connor and Robert Breer, L.C.Z.] are now discovering the merits of the art market, it is nonetheless difficult to understand why they are being presented there as if they had only recently shot their films in N.Y. on DV and had never before seen an avant-garde film.” Gass, Lars Henrik: “Experimentalfilm oder Film-Avantgarde. Ein Plädoyer für den Diskurs – und eine andere Aufführungspraxis”, in: KOLIK film, special issue 13/ 2010, pp. 61-67.

8 See http://www.kurzfilmtage.de/en/looking-back/2009/award-winners/cinema-jury.html, as of: 16 April 2010.

9 This is all the more necessary as artists wishing to work in the mediums of film and video who try to apply for film-promotion grants encounter serious problems when it comes to production funding. In view of almost across-the-board cuts in support for artistic films and the singularly inflexible application modalities, it has become nearly impossible for artists today to finance a project in German with the help of state promotional funds for film.

10 He cites as exemplary the presentation of films in the exhibition 3’, which Max Hollein, Hans-Ulrich Obrist and Martina Weinhart curated for Frankfurt’s Schirn Kunsthalle in 2004. All videos were shown in separate rooms, and the visitors were able to see on lit displays outside when the works, all of them very short, would be starting again. Accompanying the show was a catalogue with theoretical texts and descriptions of the works, and a DVD of all of the films shown in the exhibition.