1. MY BBY 8L3W, Germany 2014 © Art Collective NEOZOON

Right now, the International Short Film Festival Dresden celebrates its 30th anniversary. The festival not only bestows itself and its guests with quite a festival programme, but also with an anniversary magazine. It can be purchased as a printed edition from the festival in Dresden for the small amount of 15 euros and is also available online.

Laura Walde and John Canciani of the Internationale Kurzfilmtage Winterthur contributed an article about short film tendencies and the responsibilities of short film festivals which we republish here as a guest column.

“Just because someon’s headin for thirty, doesn’t mean he won’t still be called young.”

A thirtieth birthday is a highlight and a crisis to the same extent, as Ingeborg Bachmann said in her short story “The Thirtieth Year”, the first sentence of which we considered prefixing as a title to this piece. The second sentence reads as follows: “Yet he himself, although he wasn’t able to discover any changes in himself, has become uncertain.” The future may indeed be even greater and vaster than the past, but the course of what is to come is slowly being set now. And diminishing potentiality is the price so-to-speak that one pays to finally become a mature adult. With exis- tential questions about where we come from and where we are going marking this milestone in life.

The challenge of writing a text about tendencies in short film and the task and mission of short film festivals is accompanied by similar circumstances. Considerations about trailblazing trends are also always a reflection on what is now past. And the debates about the task or the function of public events are characterised by ideologies in a way similar to the idea of becoming an adult. Thus, what is penned below are by no means universal statements without exception, but rather the views both backwards and forwards of two people with a deep passion for short film and who over the course of the past few years – even if they are fewer than thirty – have developed a very precise idea of what they expect or desire from short film festivals.

Let us begin with a platitude: After a short period in which all cinematographic products were exactly that – short – since the early 1920s the short film has been the format of preference for the avantgarde. As a field of experimentation for new techniques, as well as for innovative visual and narrative styles and for transcending medial borders, it remains just as relevant today as it was 100 years ago. On the one hand, this certainly has to do – which is also a platitude – with its shorter production times, the cheaper production processes and its compacted claims to the audiences’ attention spans. On the other hand, this is also related to the fact that short film has been the format of choice for exercises and practicing by film students since the emergence of the film schools in the 1960s. The tendencies in short film are also more of a reflection on the current cultural, aesthetic, social and institutional trends, rather than viewing them separately or even being able to allocate them to a kind of short

film “essence”. Moreover, in the programmes screened at short film festivals, these tendencies reflect the conceptual interests of the programme makers and, at least to some extent, the preferences of the audiences. Having said this, the trends we have noticed for some time now at our festival in Winterthur and other likeminded ones include the influence of the art practice, the (re)politicising of the short film, the discourse on all things post-digital, as well as – perhaps as a counterpart to this – a certain retro- romanticism.

Several of these tendencies are not fundamentally new; trends work in waves. Accordingly, the relevance ascribed to a film also always has to do with whether it is regarded as a productive further development, an homage, or a redundant copy. The influence of the art practice is revealed not only in the films themselves, but also especially in

the screening practices and in a blurring of institutional boundaries: Such as in the tendency to conceive short films for both festival screenings, as well as on multichannel installations for gallery spaces. If for instance the obsolete analogue film footage has been kept alive primarily in the art scene over the last 20 years, in order to mediate within the gallery space so-to-speak on the medium of film and the cultural technology of the cinema, it is striking today how many young filmmakers are shooting their shorts yet again on 35 mm or 16 mm (and it would be one of the tasks of film festivals to also still be able to project these works in an analogue format when required to in the future).

Likewise, experiments are often undertaken using today’s standardised 16:9 image format, with work also being shot increasingly in the 4:3 format for instance. In this regard, the revitalising of formats should not be considered as a step back or pure nostalgia, but rather as a reference to the history of film and the performance and screening practices linked to this: The short film as commemoration and commentary so-to-speak.

A similar commentary function can also be ascribed to the numerous productions that address, in the mindset of the so-called post-internet art (image 1), the influence which the constant availability of images and the pro- fusion of audiovisual material has on artistic and social practices. What is significant about these images is not necessarily their content or their aesthetics, but rather the reflection on where they come from and how omnipresent their availability is, how they are connected together in networks and how they are received. The retro-romanticism, as is being celebrated in many successful series at present, is then perhaps interpretable as a response to our involvements with these technologies and visual worlds (2).

2. COPA-LOCA, Greece 2017 © Christos Massalas

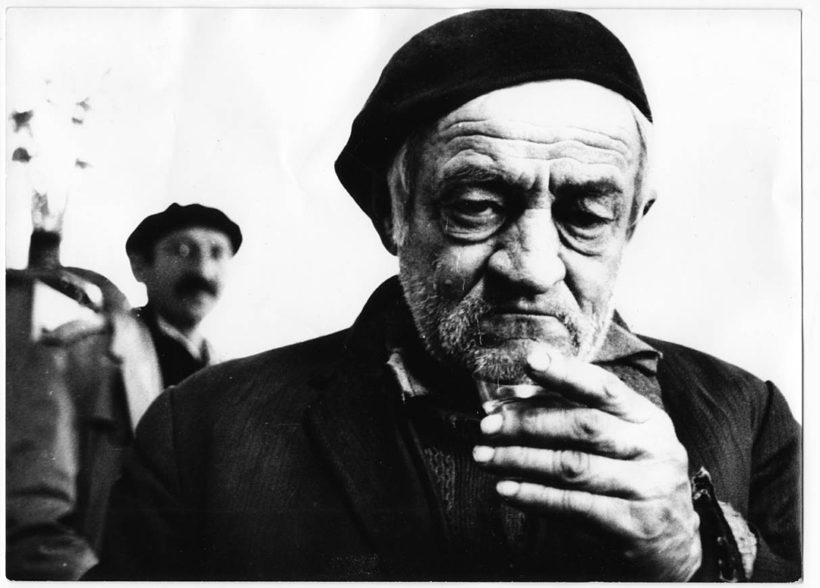

While these tendencies – the retro-romanticism in fiction films or formal experiments in artistic films – are more generic in nature, the political film (3), for which the short film form has long been an important home (5), does not arise from a specific discourse, but instead is genre overlapping and frequently even hybrid in nature. As mentioned above, the shorter production times and the lower financial outlays for short films permit the filmmakers to react reflexively to historic events and trends (6). However, such a reflex also always bears the risk that the reflection will fall short. In turn, it can thus be of interest for short film festivals to contextualise and discuss these contempo- rary documents retrospectively with the required distance in historic programmes.

3. RUBBER COATED STEEL, Germayn/ Lebanon 2016 © Lawrence Abu Hamdan, courtesy Maureen Paley, London

Short film festivals often represent the sole option for promoting these works and the network of references among them, which in fact first makes certain tendencies or currents visible. The festivals are thus duty-bound to provide the spectrum of new and exciting contributions in their competitions, and to keep alive the film history and the aesthetic, social and political discourses linked to this in curated programmes.

4. CRNI FILM (Black Film), Yugoslavia 1971 © Želimir Žilnik

For us, the following aspirations and requirements for a short film festival arise from these thoughts: We advocate thinking less in quantifiable patterns and groupings – from the mass of film submissions to the number of visitors – and instead taking qualitative considerations as the yardstick. This would mean measuring a festival on the basis of its own self-image, its own aspirations and its own uniquely personal programme-making and curatorial style. In the era of the digital economy, in which the availability of audiovisual content is not decisive (because so much is available anyway at all times practically speaking), the relevant task is to sound out, select and contextualise these works, and thus make them accessible.

For us, a central aspect of these processes is to also have well considered handling of analogue and digital formats. This is not only concerned with questions about nostalgising or even fetishising cultural artefacts, but also especially about the possibility of a specific experience and the reflection on this. And by no means would we deny that the restauration and digital projection of many historic films has helped give them a new brilliance and a new visibility. It is the task and mission of the festival to take up this discourse within the scope of the possibilities available to it (which are also often limited by financial constraints) and situatively weigh up whether the content or the form is to be accorded priority.

Ultimately, the intention is to make both historic and current film culture visible to a public audience who meet beyond the anonymity of the internet so as to look at and discuss short film programmes together. And thus it is part of a short film festival’s task and mission to actively reflect on its decisions, to assume clear position(s) and to be open to criticism – to make itself assailable. Such an attitude cannot “merely” be expressed through the selection and organisation of the festival’s programme, but also in the cooperative arrangements it has with other institutions, such as museums or international online portals, or (depending on its position and financial options) by it actively fostering and promoting a specific personal cinematic style, for instance through the awarding of promotion prizes for screenplays or production money.

Short film festivals should be aware of the responsibility they bear to the filmmakers and their works, as well as to the audiences. With their film selections comparable to a stamp of quality, it builds up a film’s reputation and in an ideal situation strengthens the trust and confidence the audience has in the programme makers. This first permits the festival to repeatedly keep an eye on the horizon as well and to introduce its audiences, within the protective scope of the festival and secure in their confidence of the work done by the selection committee, to new views and perspectives that do not necessarily work in accordance with western paradigms. But not only will a festival mature and grow through such inquisitive and persistent scrutinising of both the world outside as indeed its own practices, we would claim that by doing so it will even still be youthful in its thirtieth, sixtieth or even hundredth year in existence.